Welcome back to The Fixer, our weekly briefing of solutions reported elsewhere. This week: a millennia-old approach to controlling Australia’s wildfires. Plus, a city gives its Housing First strategy a personal twist, and Sydney engineers decentralize the plastic recycling industry.

Slow burn

Australia has worked to contain its wildfires with every modern firefighting tactic there is, but it turns out millennia-old Aboriginal methods could be the way forward.

Australia’s Aboriginal communities have long used “defensive burning” practices, creating small, intentionally lit fires to burn away undergrowth that fuels larger, destructive ones. In 2013, the national government began funding these communities’ efforts. The funded areas now cover an area the size of Portugal. They are mostly in the country’s north — areas that, so far, have been less affected by the out-of-control fires devastating towns in the south, thanks to the preventative burning efforts.

“Fire is our main tool,” said Violet Lawson, one of the program’s participants. She lights hundreds of small fires each year on her land to prevent larger fires from taking hold. Efforts like hers have received $80 million through Australia’s cap-and-trade system, and have reduced greenhouse gases generated by wildfire there by an estimated 40 percent.

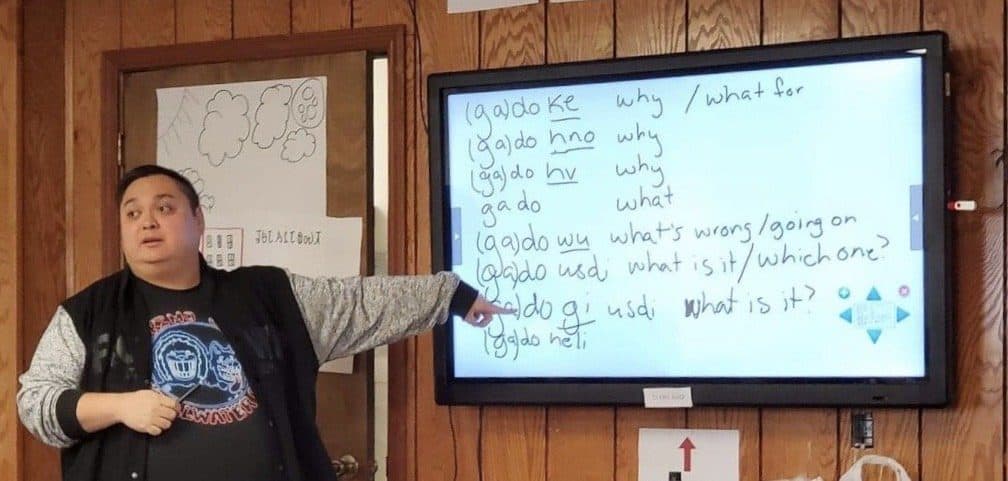

Now, Native American tribes in California, which have long practiced defensive burning as well, are hoping to receive similar government support. Since 2014, members of the Yukon tribe have worked with prison inmates brought in by Cal Fire to conduct controlled burns, but their efforts are far smaller in scale. While the Australian program encompasses 90 million acres, California’s covers just a few thousand. “If we are going to make our landscapes resilient, and thus our communities resilient, we have to follow these practices that are tried and true,” said one fire expert from Cal State.

Read more at the New York Times

Who are your homeless?

Another city is pursuing a Housing First strategy to eliminate homelessness, and it’s adding a twist: a “command center” tasked with collecting real-time, name-by-name data from every homeless person in the community.

Rockford, Illinois’s effort started with veterans. In 2015, the city began bringing together all of its groups that work with vets to identify which ones were struggling with housing insecurity. The push grew out of the Obama administration’s 2014 call to end veteran homelessness, and “changed [Rockford’s] entire system, everything we do,” according to Angie Walker, the city’s homeless program coordinator.

With the system in place, Rockford began adding more groups — the chronically homeless, homeless youth, homeless families — working to eliminate homelessness for each one by one. While many other cities’ Housing First models rely on subsidized housing and single-day “snapshots” of homeless data, Rockford’s command center tracks every homeless resident’s situation in real time. “If John Smith is on the list, we talk about where he’s staying, ask who has had contact with John, and figure out where we can get John housed at and how fast can we do it,” Walker says.

Using these methods, Rockford has functionally eliminated veteran homelessness, and is on track to do the same for youth homelessness in the next few months. By the end of this year, it expects to have its final focus, family homelessness, down to functional zero.

Plastic pioneers

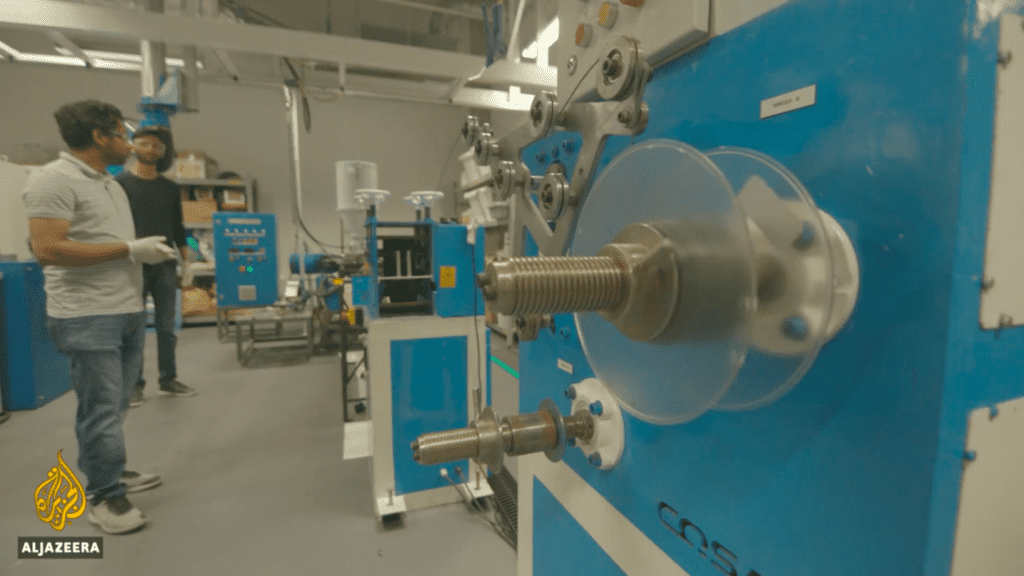

China used to be the world’s preeminent recycling destination, but in 2018 Beijing started turning away most imported plastic waste. It had always been an imperfect solution — transporting discarded Coke bottles across the sea is a wasteful enterprise in and of itself. What if plastics could be recycled closer to home?

Engineers in Sydney have developed a device that might make that possible. Their “micro-recycling factory” uses heat and pressure to turn crushed plastic into unmolded resin. This can then be fed into 3-D printers as the raw material to create new objects. The method decentralizes the recycling process, turning unwanted plastic into a high-value product closer to where it’s needed. The technology isn’t commercially available yet, but shows promise as a way of transforming the global supply chain of recycled plastic into a local endeavor.