For many years, every time it rained in Charlotte, North Carolina, Elaine Aldridge ventured out to move the cars from her carport to higher ground across the street, lest the creeks in her backyard flood them.

When she bought the 1200-square-foot house in 1981, Aldridge never expected that she’d end up replacing several air conditioners, a dryer, carpets and floors due to six floods in 15 years. Floodplain restrictions were placed on the house, which meant the Aldridges couldn’t expand its footprint, and they didn’t make the house an easy sell on the real estate market, either.

“We were really stuck in that house,” Aldridge recalled. “We didn’t think we’d ever be able to leave.”

Many people in Aldridge’s situation remain stuck like she was for a long time. Millions of Americans are at risk of flooding every year, and as climate change increases the frequency and intensity of storms, that number is growing. While the federal government has a program to help people like Aldridge by purchasing houses that exist on floodplains to allow their owners to relocate, the average buyout takes years to process.

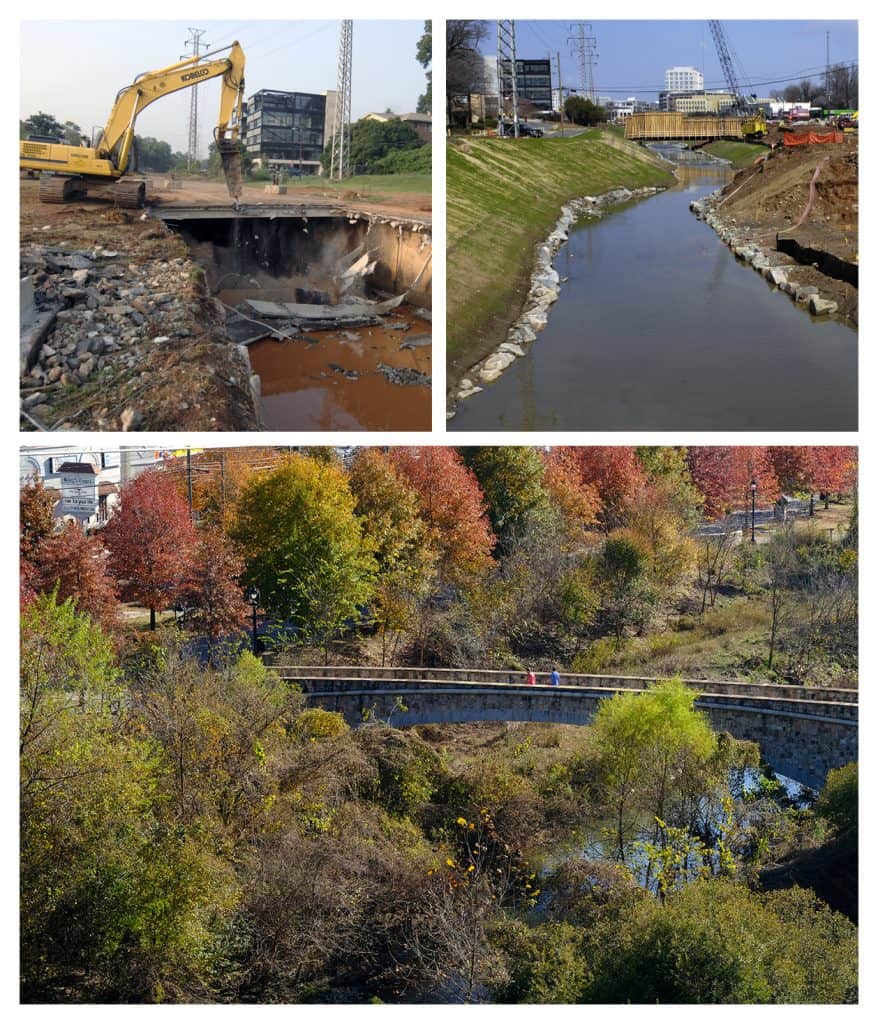

But Aldridge’s community is different. Thanks to a unique, homegrown local flood buyout program, the retired Aldridges now live in a larger home a few towns over, and an empty field sits at the corner of the two creeks where they used to live, ready to sop up flood water when the rains hit. Across the street from their old home, buyouts in the early 2000s made way for a popular greenway where residents bike and walk to a nearby shopping center.

While thousands of Americans wait years for the federal government to step in and save them from their soggy homes, Charlotte and its surrounding Mecklenburg County have done something special: they’ve proactively tackled the impacts of flooding to give their citizens better lives while creating a local solution to a major national problem.

Crossing their fingers

Flooding in America is expensive business. When low-lying properties or homes near waterways, like the Aldridges’, repeatedly flood, owners may spend more money on repairs than the houses are even worth — just an inch of water in an average home can cause $27,000 of damage. In the late 1980’s, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) started funding flood buyouts nationally when they found that it’s better for both the economy and public safety to buy owners out and demolish flood-prone buildings, leaving open land to absorb future flooding.

FEMA buyouts work like this: If an area receives a presidential declaration of emergency, it can apply to FEMA for buyouts. FEMA pays for 75 percent of a property’s value and leaves it to local governments to cover the remaining 25 percent. And by all accounts, it’s worth it. FEMA estimates that for every dollar spent on flood mitigation, including buyouts, the government saves six dollars from prevented casualties and injuries, repair costs, shelter costs, search and rescue teams and economic losses. Adding undeveloped land to absorb floodwater helps mitigate future floods, so it’s a win-win.

Despite the benefits, however, it can take months for FEMA to even announce buyout funding, and a recent report by the nonprofit National Resources Defense Council showed that homeowners waited a median of five years for a FEMA buyout, either wasting their money and time repairing houses scheduled for demolition, or worse, living in damaged and possibly dangerous homes.

After Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, a full 20 percent of homeowners who had been approved for buyouts dropped out of the program during the wait, either selling before the buyout or deciding to stay and cross their fingers that they won’t get hit by the next flood instead of dealing with FEMA bureaucracy.

A radical decision

Different cities have different strategies for flood mitigation. In New Orleans, levees are supposed to hold floodwaters, though they broke during Hurricane Katrina. In Tulsa and Houston, large retaining ponds fill with water during floods.

In Charlotte, however, a group of community stakeholders formed after two huge floods in the 1990’s and decided something different: floodplains are meant to flood.

That decision led to a suite of local mitigation measures that look different from those in other communities. First, the city and county formed a joint storm water utility — Charlotte Mecklenburg Storm Water Services (SWS). They created a county-wide fee for fixing aging pipes and dealing with other storm water needs. The fees are based on area and today range from $2.89 per month for small structures in unincorporated Mecklenburg County to over $25 per month for 5000 sq. ft or more of impervious surface area in Charlotte.

They used that money to fund their own buyout program — one that would actually work for their community. After wrestling with FEMA’s bureaucratic system and realizing that many of the local weather events that hit Mecklenburg County don’t make it on FEMA’s radar (meaning federal funding isn’t even an option) SWS decided to do it themselves.

That “Quick Buy” program bought out the Aldridge’s home on September 17th, 2018, right before Hurricane Florence hit. Immediately after a flood, or even before as in the Aldridges’ case, the utility contacts homeowners and offers a buyout before they’ve begun repairs or sold their home, in contrast to the slow pace of FEMA buyouts.

The program has other options for homeowners too. For example, funds also go to help owners retrofit floodplain properties by elevating HVAC units or sealing off basements.

“This is in contrast to how most other communities handle their flood mitigation program: a lot of them, it’s like a rollercoaster ride,” Dave Canaan, director of SWS said. “You’re not doing much, then a hurricane comes… there’s [FEMA] funds to go do buyouts and elevations. Then the declaration is retired, the money goes away. And then there’s really no mitigation until the next flood.”

Nowadays, Canaan estimates that no more than five percent of SWS’s buyout funds come from federal funding, with the local fee covering almost everything.

Futureproofing

It’s one thing to mitigate current flooding and deal with existing properties. But one of the real innovations in Charlotte-Mecklenburg is in how much they’ve looked forward to future development in their flood planning to pre-empt future disasters.

When the Aldridges bought their house, it wasn’t in a floodplain. Back then, no one expected that Charlotte’s population would nearly triple over the next 40 years. The increase of impervious surfaces created by a development boom in the 1980’s and ‘90s expanded Charlotte’s floodplain, and homeowners had to deal with headaches as water flowing from new parking lots and buildings overwhelmed existing drainage systems.

Keen to not continue that trend, the 1990’s stakeholder group created a floodplain guidance document, still updated and used today. The major innovation was updating floodplain maps so they wouldn’t be caught flat-footed by development. Charlotte-Mecklenburg was the first in the country to use maps that take into account future growth and land use, instead of just existing impervious surfaces as FEMA maps do.

Other communities have taken note. “As a result of the work that Charlotte-Mecklenburg did, communities now across the US have the option to ask FEMA…[to do] the community floodplain,” Canaan said. “Theoretically, no matter when Charlotte-Mecklenburg fully builds out, when somebody builds around the floodplain, they won’t flood in the future.”

SWS maps also give more buyout priority to properties where swiftwater rescue teams would need to deploy, or which abut existing greenways or previously bought-out homes. Canaan said he has worked with the Department of Homeland Security to put SWS’s floodplain mapping tool into software and a guidebook for other communities to use.

The utility painstakingly collected data on all 3000-some buildings in the floodplain, and now knows the first-floor elevations of each property.

“Floodplain maps are so much more cost effective to preventing flood losses,” Canaan continued. “The floodplain buyout program is still very beneficial to the community, but it’s also very expensive when you compare it to the floodplain mapping program.”

Successes and challenges

Charlotte’s program has spent about $60 million buying 424 buildings, freeing up 182 acres of open space and helping relocate 650 families with a local realtor partner. Canaan estimates that the program has saved $25 million in losses, and those savings will rise each year.

Having a dedicated funding source for the program has helped immensely, especially since the program was able to continue through the 2008 recession, but so has the stakeholder group and community input.

The program is not without its challenges. Charlotte is in the middle of a well-documented affordable housing crisis, which makes it harder for potential buyout beneficiaries to find new homes. Canaan said that in most years, they’d had very high participation rates of around 80 to 90 percent of homeowners taking buyout offers, but two years ago, it dropped to 30 or 40 percent.

And though the Charlotte buyout program may be faster than FEMA, property owners still become frustrated by the months it takes for a buyout to finish after initial contact. Such owners still pay property taxes, flood insurance and utilities on top of their mortgages for every month that passes.

Similar programs won’t work everywhere, Canaan warned. For instance, a coastal community which relies heavily on shipping might lie entirely in a floodplain.

“Where are these people going to live? Who’s going to be there to bring the ship in and unload the containers?” Canaan said. “That’s why it’s not just an economic challenge. It’s also a housing and a social challenge.”

But for Charlotte and Mecklenburg, the program seems to be working.

“It brought closure,” Aldridge said. “We were so glad to not have to deal with it … We have a lot of good memories in that house; we raised a child in that house, but sometimes change is good and it’s okay to move on.”