How should one think of a nation, institution or company that has pioneered innovation and found solutions to seemingly unsolvable problems, but also has aspects we find objectionable, even despicable? How do we balance good and bad? Can we separate the two, or are they inexorably linked?

More specifically: How do we think about a country that has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, has backed and advanced renewable energy technology, and mostly avoided military imperialism, even as it violates the human rights of millions, persecutes minorities, wreaks havoc on the environment and embraces authoritarianism, surveillance, censorship and corruption? If we cheer the good stuff, are we tacitly endorsing the bad? Does it have to be all or nothing?

With Reasons to be Cheerful we try to present the good stuff. But sometimes the good stuff is mixed in with not-so-good stuff, sometimes even with fairly horrible stuff. I’m going to take China as an example of this dilemma. Watching the Beijing-supported crackdown on democracy activists in Hong Kong, and reading about the brutal Uyghur detention camps in Xinjiang province, one wonders whether it is bad form to highlight even the most indisputably good solutions from China. Like German coal-powered electric car infrastructure, is China good or is it bad? It’s complicated.

Poverty reduction

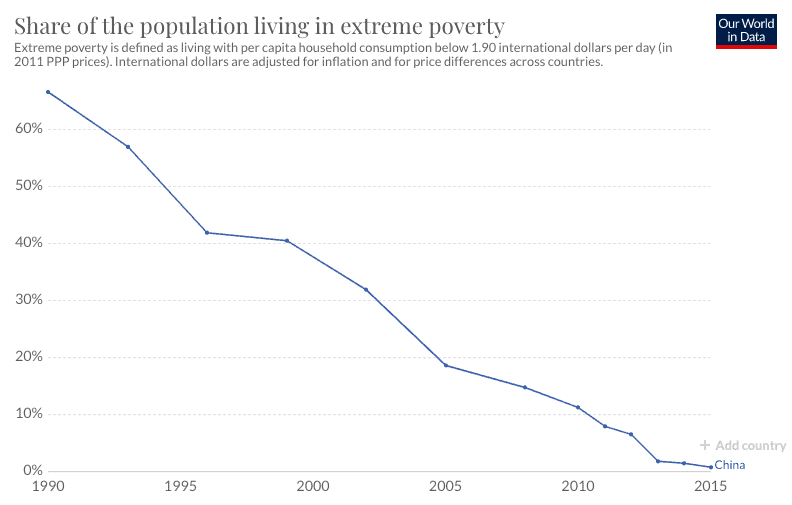

China has raised millions out of poverty. The number of Chinese people living in extreme poverty was 88 percent in 1981 and 0.7 percent in 2015. How many people does that amount to? The numbers vary depending on the source, but 500 million would be a very conservative bet. (The World Bank says 800 million and President Xi Jinping says 700 million.)

Whatever the exact number, it is historic — no other country in the world has been able to do this. Needless to say, achieving it took a LOT of central planning, which can be an advantage when you’re an authoritarian regime. You don’t have to ask permission. You aren’t beholden to voters.

Some credit for this massive change dates back to the early 1980s when rural poverty was targeted. Land was distributed in more equitable ways and new technologies made farming more efficient. Farmers were no longer serfs toiling on massive collective farms and the efficiency gains meant that fewer folks were needed to run the farms, so many rural folks migrated to the cities where they hoped to find other work. As a result, there emerged a massive source of cheap labor around the urban centers of China. The world took notice.

Various factors beyond just cheap labor seduced the world into making use of all these workers: China’s investments in its transportation and infrastructure, plenty of available energy, a system for efficiently resolving business matters… Even time spent in customs makes a difference — getting stuff in and out of Bangalore takes almost twice as long as it does in Shanghai or Guangzhou. For foreign companies any of these things can be a deciding factor in whether to work with China.

As time went by Chinese workers became more skilled, and the government began to prioritize high-value industries like green tech, robotics and telecommunications. With these changes, incomes went up. This drove some global companies to seek cheaper workers in places like Vietnam and Indonesia, but it helped many Chinese workers escape the poverty trap.

The flood of workers into urban centers was a strain, but a government subsidy paid to city residents helped, as did progressive taxation. The effect was that three-quarters of the reduction in world poverty was due to China alone.

Nations around the world seeking to reduce poverty are looking to China for lessons in how they might do it. But should they? Practically speaking, some of China’s methods would be difficult to replicate elsewhere. For instance, many of those farmers who moved to the city didn’t do so by choice — they were forced there by the government, which effectively decides where folks will live by restricting their social benefits by geography. And China’s rise as an economic superpower has included plenty of pain, including a disregard for the environment, public health and workers’ rights.

Then again, some countries might be willing to accept these faults in exchange for a China-sized economic boom. Who cares about freedom of speech when you don’t have enough to eat? As the cynical saying goes, “Development first, democracy later.”

International power and loans

China invests in a lot of developing countries, building (or supporting via loans) infrastructure like roads, dams, schools and railways. In addition to being key to its plans for economic expansion, these international partnerships are China’s chosen form of “soft power.” But it’s not always clear how much the nations it’s partnering with benefit from the projects.

China, for its part, almost always seeks to benefit from these projects in some way. They’re not gifts — China uses them to extract resources, exploit cheap labor, or provide infrastructure for overseas Chinese businesses. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re bad for the recipient country — not all of this investment is the 21st century version of colonialism. Some of it is much needed by the client nations, who are clamoring for infrastructure that only China appears willing and able to build for them.

Then again, some of it they don’t need. In recent years, Chinese companies have invested twice as much in Africa as American companies, and more than twice as much as the World Bank and the IMF combined. These projects are often funded by loans from Chinese state banks, which sometimes leave the recipients mired in unaffordable debt. There are shades of the World Bank and IMF here, which often saddled nations in South America and elsewhere with massive debts before forcing them to accept austerity programs. When the loans can‘t be repaid, China has, at times, declared ownership of the port, railroad or airport it just built.

In Malaysia, which once welcomed a surge of Chinese investment, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad has grown concerned about “a new version of colonialism.” Mahathir cancelled Chinese projects worth almost 23 billion dollars, seeking to avoid the fate of Sri Lanka, which defaulted on heavy Chinese loans and eventually agreed to give Beijing control of a major seaport for 99 years.

In general, economic partnerships like these are China’s way of reaching out to the world. As a burgeoning superpower, China knows it needs to make long term friends if it is to operate in those countries …and a more prosperous country eventually becomes a future trading partner. China wants some of their resources, to be sure, and it wants to sell Chinese goods. They see a potentially huge market. But there’s usually a power imbalance involved in these partnerships that gives China the upper hand. The trouble arises when China uses that advantage to exploit the recipient country.

The U.S. once famously invested in European countries this way, too. After World War II, the Marshall Plan was a way to woo Europeans who might have tilted towards Russia and communism. It also made trading partners of nations whose economies had been decimated. It worked. Today, the U.S. meddles in a lot of countries, overtly and covertly, often militarily, and often ends up both leaving a mess and making enemies as the recent release of communications within the U.S. military in Afghanistan show.

Climate and carbon

The environment and climate change is another area in which China is a study in contrasts, having wrought devastating destruction while pointing the way toward a greener future.

Even as it produces one-quarter of the world’s harmful emissions, China has taken huge steps to reduce its carbon footprint. Its state-owned enterprises have invested heavily in solar, surpassing their 2020 goal in 2017. The country appears to be on the verge of finally implementing the world’s largest national carbon market, covering 1,700 energy-related companies, which it launched in 2017 with the help of the Environmental Defense Fund. It’s on track to meet the emissions limits stipulated by the Paris Agreement.

China is quite serious about this. As mentioned earlier, many nations and people around the world look to what China is doing as an example to follow, even if its faults are well publicized. These countries also want to raise their people out of poverty and become a force in the world. But will they be drawn to emulate the totalitarian and rapacious side of the Chinese state?

China, as the Western press loves to point out, has a horrendous human rights record. The Uyghur muslim population in western China is gradually being decimated. More than a million are in what are essentially concentration camps working as forced labor. (China denies this, but the atrocities are well documented.)

But the Western capitalists are complicit in this, as well. From an op-ed by artist Ai Weiwei in the New York Times:

Westerners may think of Xinjiang as a distant and mysterious place, but in some ways it is not very exotic. Multinational corporations including Volkswagen, Siemens, Unilever and Nestlé have factories there. Supply chains for Muji and Uniqlo depend on Xinjiang, and companies such as H & M, Esprit and Adidas use Xinjiang cotton.

Might a “culturally different” nonwhite labor force play a role? People in no need of control because a harsh Communist government is already doing that work? In Xinjiang, as elsewhere in China, bosses from East and West have exchanged benefits, formed common interests and have even come to share some values. The chief executive of Volkswagen, which leads China in car sales, was recently asked for the company’s comment on the concentration camps in Xinjiang. He answered that VW knew nothing of such things, but the recent Xinjiang papers show otherwise. VW not only knew of the camps but signaled its readiness to go along.

The conundrum

So, how do we morally deal with situations like this? (And there are lots of them — China is just a giant example.) The world isn’t black and while — it’s vast and complicated. There is, one hopes, room for nuance, or there should be.

Pharmaceutical companies, for example, create medicines that save lives, but they also engage in ruthless predatory practices and have tacitly encouraged addiction. One in particular, the Sackler family, has profited from America’s opioid crisis. That same family also famously supports museums and the arts. Many of those arts institutions are now refusing Sackler money — in essence, they are saying that the family’s bad deeds are so egregious that they render their good ones irredeemable.

Social media and other forms of digital technology are amazing and often helpful, but they also, by systemic design, foster extremism, depression, alienation and addiction. Democracy is at risk. Craziness is on the rise. Data, AI and algorithms can be used to correct injustices, but also to exacerbate them. They can promote efficient and enlightened social and health initiatives, or reinforce existing biases and increase inequality. Bill Gates, one of the visionaries who brought us these wonders, is mostly viewed now for the good work his foundation does, and not as the rapacious monopolist he once was. Sometimes the bad simply gets forgotten. We forget the sordid past, or see what we want to see.

For proof, look no further than the rise of the industrialized Western world, which occurred in very similar fashion to the way China’s rise is occurring now. A century ago, America and Europe ignored human rights, environmental concerns and basic safety protocols in their relentless pursuit of development. Economies were built on slavery and exploitation. Today, China is doing something similar, as are many other developed countries. There are lots of double-edged swords. How do we know which ones to pick up and which to leave alone? Can we separate the positive from the negative, or are they bundled too tightly together?

How shall we be?

As individuals and as a society, we like things to be simple, black and white, bad and good. We often evaluate situations as if they could be put on utilitarian scales, the good on one side and the bad on the other, to see whether more people are being helped than hurt. Does good cancel out bad? Can we use this utilitarian calculus, or is it flawed?

It seems to me that attempting to itemize the positive and negative on a virtual scale is not really the way to go. Good does not really cancel out bad. That logic is close to the practices of the late Medieval Catholic Church, which sold “indulgences” (heavenly “get out of jail free” cards) to wealthy individuals.

Imagine there’s no heaven. Imagine no karma, no judgment by outside forces. It’s just us, humanity, who collectively assign value. We are social animals, and cooperation and other kinds of beneficial and prosocial behaviors are, sometimes surprisingly, part of our nature. Those parts should be encouraged. By looking at longer range effects and including externalities in the cost of doing business, by making repercussion part of the true costs of policies and business, we become stewards of our common humanity.

It’s tricky, though. To much of the world, especially the developing world, China’s economic success serves as a practical example to emulate. And certain parts of what they have done — lifting millions out of poverty, investing in renewable energy, eschewing military conflict (for now) — can and perhaps should be emulated. One doesn’t need to have a repressive authoritarian structure to learn from those practices. Can we learn from the best aspects of China’s economic, environmental and soft power initiatives and separate them from the authoritarianism? Should we?

Can that distinction and separation be made? Can we extricate the good from the bad? Is that more than our brains can handle? Can we be less absolutist and take a deep breath and accept more nuance?

Atypically, this piece poses a question rather than pointing the way toward a solution. I’m asking myself if maybe I need to reorient my thinking, embrace more nuance, and accept that some solutions come with caveats.