For all the attention it might draw, when a brand releases a line of clothes made of ever-more unusual, allegedly eco-friendly materials like algae sequins, grape leather or rotten milk, chances are the real environmental benefits are low.

“A cool new next-gen material might get a lot of buzz, it could look good, but the production capability may not be enough,” says Lewis Perkins, president of the Apparel Impact Institute. “Where’s the long-term, systematic improvement?”

Perkins argues that rather than using novel materials or promoting one-off campaigns, the best way to decarbonize the fashion industry and make it more sustainable is a system-wide approach — largely using unsexy, tried-and-tested techniques.

When the San Francisco-based Apparel Impact Institute launched at the end of 2017, it set out to deliver exactly that.

The institute estimates that existing solutions — such as phasing out coal use, maximizing energy efficiency, increasing use of low-carbon fibers such as recycled polyester and shifting manufacturing to renewable electricity — can cut the industry’s emissions by 1.2 gigatons, the equivalent of taking 200 million cars off the road.

According to a joint report by the institute and nonprofit Fashion for Good, an “aggressive acceleration” of implementing currently existing solutions could allow the fashion industry to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, a target in line with the Paris Agreement. “We can scale these proven solutions,” says Perkins.

Transformative change is needed for the $2.5 trillion fashion industry: It produces 10 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions, and textile production is responsible for 1.2 billion tons of emissions a year. Clothing production creates a fifth of global waste water and 92 million tons of textile waste a year.

“It is clearly one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gasses,” says Teresa Domenech Aparisi, associate professor in Industrial Ecology and the Circular Economy at University College London. “And it produces huge amounts of excess and waste.”

Yet while much focus has been on the role of consumers in producing this waste, the Apparel Impact Institute is instead targeting the supply side. According to the World Resources Institute, 96 percent of a brand’s carbon footprint are Scope 3 emissions, or in other words, from the manufacturing supply chain.

The Apparel Impact Institute knits together the efforts of brands, manufacturers and industry stakeholders to help identify and scale up solutions that work, in a way that reverses the previous trend of individual, siloed-off endeavors. “Where there’s an overlap in production, rather than one brand individually asking a company for thermal heat tech, we can have a strategic process working together,” says Perkins.

Apirisi, who has done analyses of the carbon footprint of clothing, agrees with the need for system-wide change. “It definitely must be collaborative across the industry,” she says. “It’s not enough for one manufacturer to change part of their collection to recycled cotton if you don’t ensure there is good recycling of cotton at the end.”

That collaborative approach appears to be having some success. In 2021, the institute worked with 27 brands and 295 facilities, spanning from India to Italy, South Korea and the US, in the process cutting 316,451 tons of emissions and saving 2,903,575 cubic meters of water. Although the figures for 2022 have not yet been published, Perkins says that there has been a “significant” increase in the savings.

However, some tricky obstacles lay ahead. Just over half of the industry’s manufacturing emissions come from thermal energy, which is often required for dyeing and finishing material but relies almost entirely on coal and gas.

“We haven’t got a straightforward solution for that yet,” says Perkins.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Yet the Apparel Impact Institute does see room for innovation, too. It estimates that emissions could be cut by one gigaton through the use of more experimental tools such as bio-based materials, plant-based leather and increasing textile recycling.

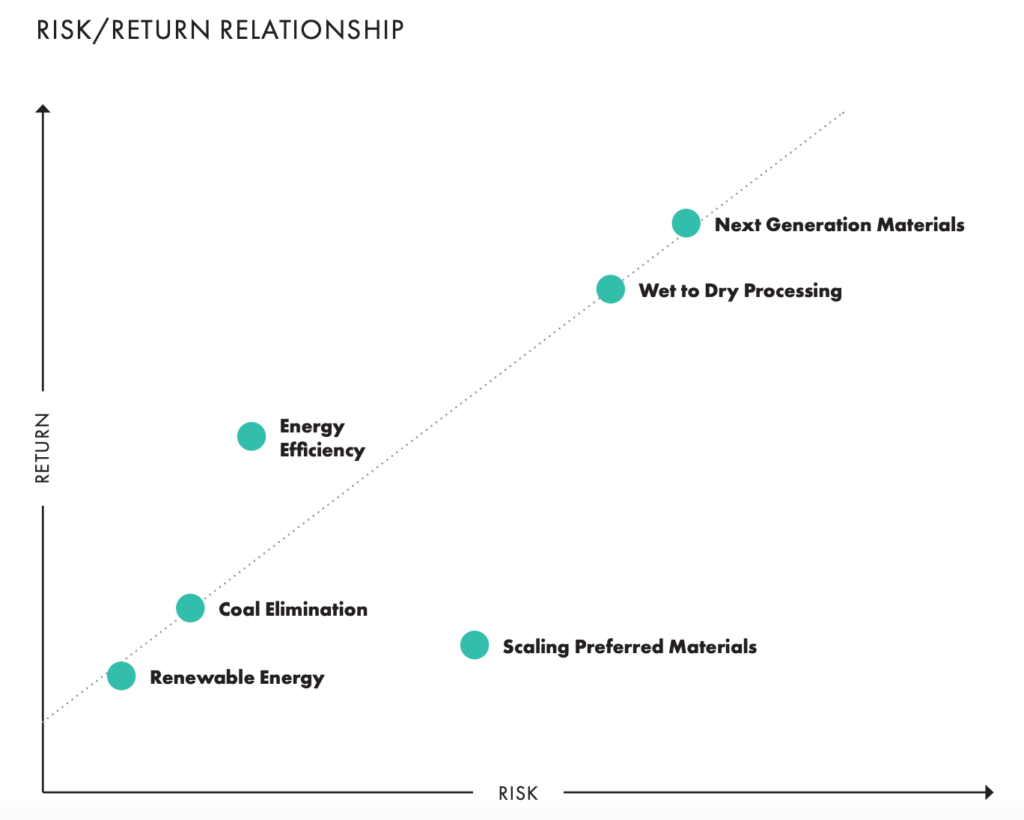

In January, it launched a call for proposals for a $250 million Fashion Climate Fund — raised through industry and philanthropic donors — for solutions that could be part of the Climate Solutions Portfolio, a registry of cutting-edge, scientifically proven technologies for issues like thermal heat, concentrated solar and modular hydrogen. “To date, we haven’t placed risky bets,” says Perkins. “But we are reviewing our appetite for risk. But ultimately, any projects we support will need to verify the claims made.”

But while the fashion industry is making improvements by itself through forms of self-regulation, some argue that national and trans-national policy is required in order to fundamentally change how these businesses operate.

A report published in January by Zero Waste Europe, an advocacy group, concluded that the current model of fast fashion, seasonal collections and trends is “one of the main drivers of overconsumption, resource depletion and social exploitation.”

“We can’t just make the products more green, we need to address these business models that rely on aggressive marketing and vast overconsumption,” says Theresa Mörsen, policy officer at Zero Waste Europe.

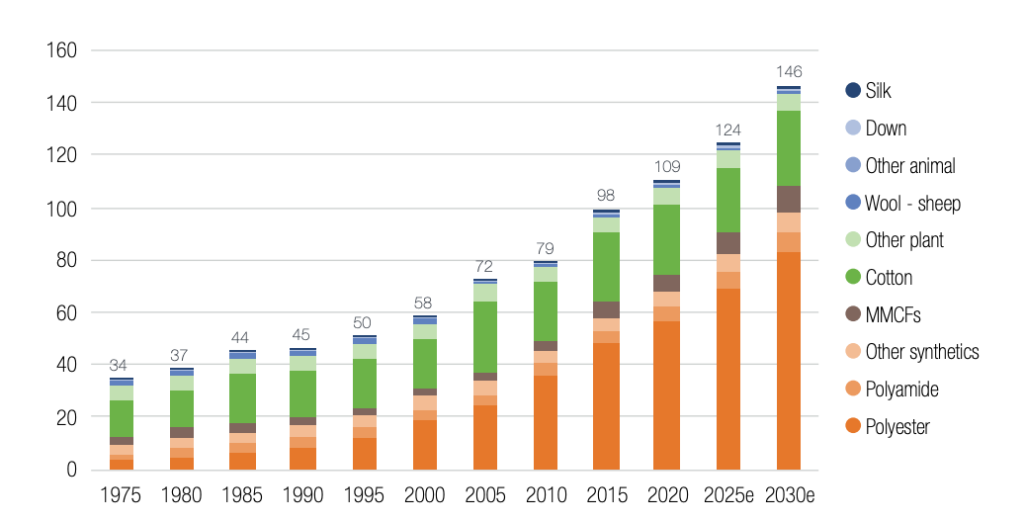

The scale of overproduction is enormous. Globally, an estimated 92 million tons of textiles waste is created each year. By 2030, the quantity of clothes we throw away is projected to reach 134 million tons and then 160 million tons in 2050.

“It’s been exacerbated by fast fashion,” says Apirisi. “A lot of selections and clothes are put on the market continuously, with large volumes of low-quality textiles.”

At the same time, the creation of waste, which often ends up in developing nations, is heavily skewed towards wealthier countries. The average American throws away around 37 kilograms of clothes every year. And around 85 percent of all textiles thrown away in the US are either dumped into landfill or burned. Much ends up abroad, illegally.

“Land use and water use to produce these clothes mostly occurs outside of the Global North,” says Mörsen. “But most fashion products are consumed in the Global North. They are worn a few times and then end up in landfill on the other side of the world.”

Mörsen says there have been interesting policy developments, such as the European Union’s Strategy for Sustainable Textiles, focusing on eco-design rules. From 2025, textile recycling will also be mandatory in the EU. But these policies are limited in what they can achieve. “We need to change the entire business thinking,” she says. “We need to think about sufficiency. It’s better to increase the quality of the clothes.”

It’s a point acknowledged by the Apparel Impact Institute, which calls for “extending the useful life of garments, re-commerce, increasing rentals, improvements in materials efficiency, and reduction in overproduction” in its goals.

However, threads of hope already exist in that regard for the fashion industry, which can no longer dress up the naked truth of its carbon footprint. The French company LOOM, whose motto is “less but better,” does not advertise or have seasonal collections, and rejects pricing (like $9.99) that encourages over-consumption.

“We need to make the industry follow in these footsteps,” says Mörsen. “Because if we don’t, then the world is in real trouble.”