The American eel is a slippery, mysterious fish. Eels live out most of their lives in the freshwater rivers and estuaries of the United States, from New Mexico to South Dakota to Florida to Maine. But when it comes time to reproduce, the species ventures far out to the Sargasso Sea, the area of Atlantic Ocean located south of Bermuda some 900 miles off the eastern coast of the US — or so we think.

Scientists have never actually witnessed wild eel reproduction, only evidence of it. But to the best of our knowledge, there, in the open waters of the Sargasso, female eels lay their eggs and subsequently die. When the orphaned eels are hatched and ready, they return to the continental US, guided by a genetic GPS back to the inland waterways from whence their parents came.

But today, the American eel’s great mysterious migration is more perilous than ever. The species was first recognized as endangered in 2013, and wild populations are estimated to have dropped by as much as 50 percent over recent decades.

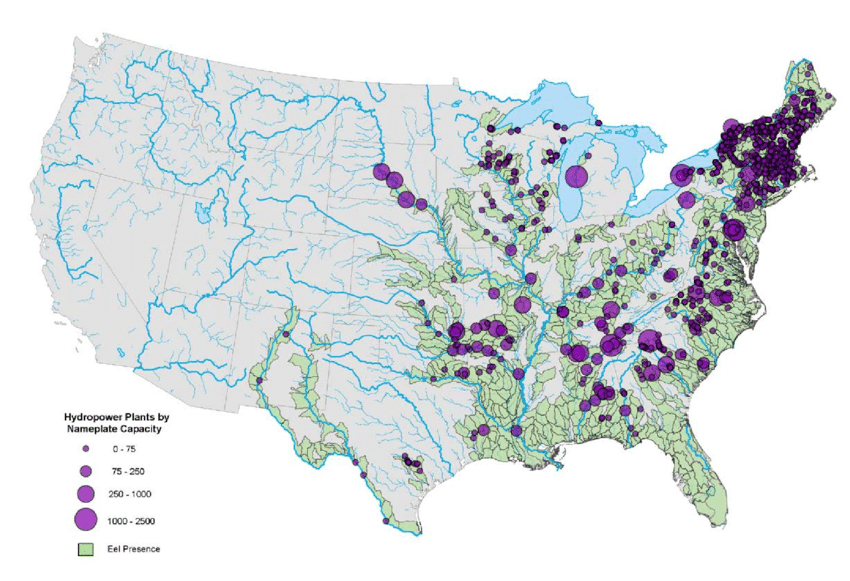

The journey between the States and the Sargasso Sea is complicated not only by the trawling nets of fisherman, but the steep concrete walls and sharp steel turbines of hydroelectric power plants, over 900 of which are located within the native range of the American eel.

Such dams provide huge amounts of emissions-free energy to the US, making them an essential tool in fighting climate change. Balancing this benefit with the needs of the eels –– and many other aquatic species –– is propelling a movement to align the dual goals of producing abundant clean energy while protecting biodiversity: turbine by turbine, eel by eel.

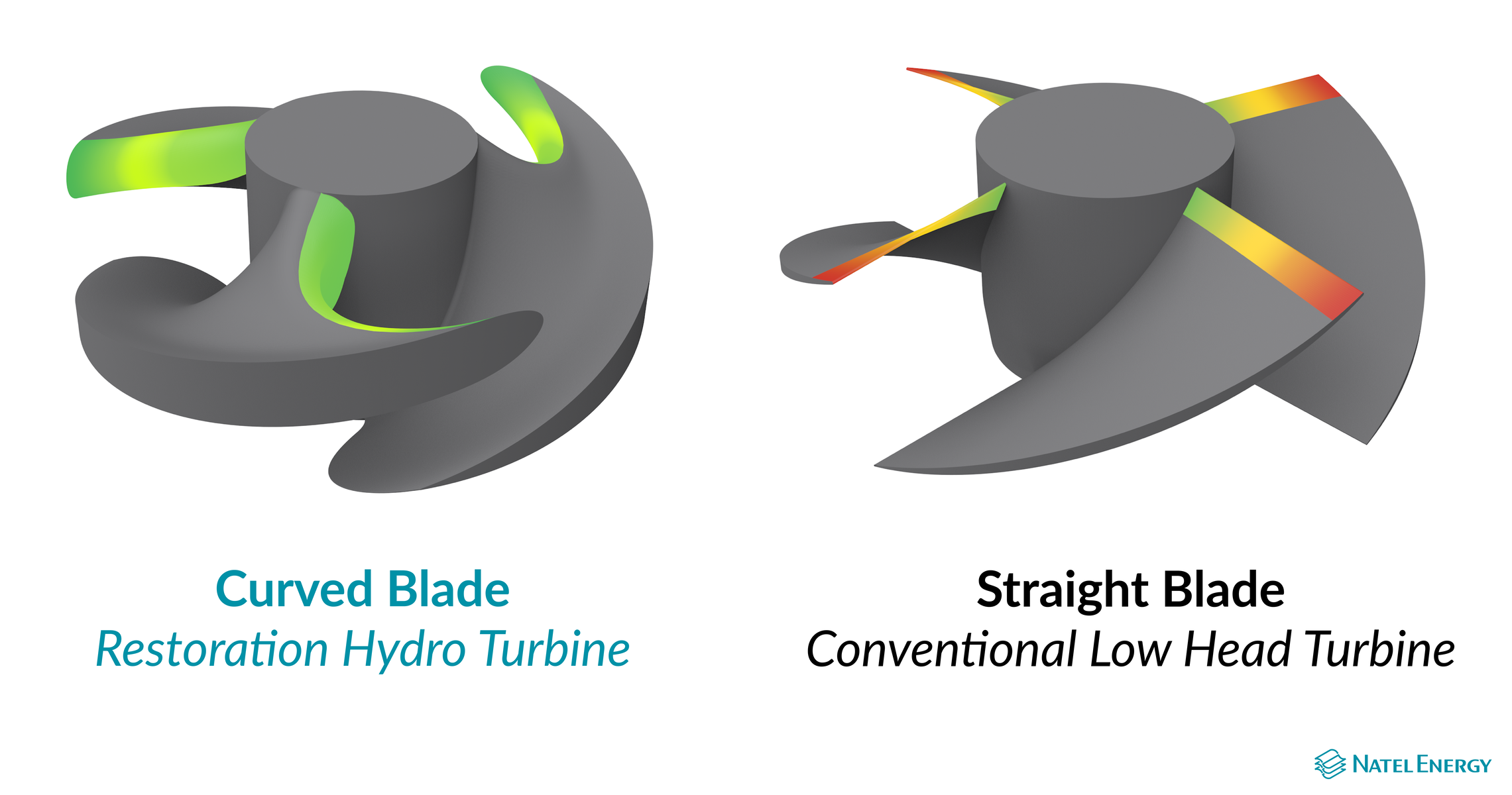

In a hydroelectric power plant, water is channeled through turbines to spin the blades that power generators. The sharper these blades are, the more efficiently they can cut through the current to generate power.

“The typical way to design turbine blades is to have a leading edge that is as sharp as possible, which is intuitively not going to be very kind to fish,” says Abe Schneider, chief technical officer and co-founder of hydropower developer Natel alongside his sister, Gia Schneider, Natel’s chief executive officer. On average, hydropower turbines kill 22 percent of the fish that pass through them. With their elongated bodies, eels are especially vulnerable. Survival rates for eels passing through traditional turbines can be as low as 40 percent.

Natel’s mission is to outfit dams with blades that give fish a fighting chance. The company’s Restoration Hydro Turbine system is designed to allow fish safe passage through the turbine itself. It does so through blades with leading edges meticulously blunted, curved, and slanted to minimize danger without compromising efficiency. Moreover, the turbines minimize the gaps between the blades and the turbine walls, vastly reducing the chance that a fish gets trapped between moving and stationary parts.

A study recently published in the journal Transactions of the American Fisheries Society documents the success of the RHT design. In a test, 131 American Eels passed through the turbine as it spun at a rate of 667 rotations per minute — eleven rotations per second. All 131 eels survived, and though some were struck by the turbines, none experienced serious injuries.

Allowing fish to safely pass directly through turbines is a new frontier in making dams fish friendly. Traditionally, hydro plants attempted to keep fish out of their turbines altogether, blocking their path with screens or sending them around through bypasses. No solution is perfect. Screens for juvenile eels, for instance, sometimes must have gaps no bigger than two millimeters in width. These screens can quickly become clogged and even potentially harm fish that end up trapped against the mesh. (And fish inevitably slip through the screens.)

And while bypasses like fish ladders and spillways allow for some fish passage around turbines, they are not enough to negate the plants’ fracturing effects on local ecosystems. Even with bypasses, dams prevent water temperature equalization, trap sediment, disrupt spawning grounds and reduce oxygen concentration in river waters, among other impacts. “The turbine can’t solve all of [hydro’s] problems, but it can play its part,” says Schneider.

Thus far, Natel has completed three hydro installations: in Oregon, Maine, and Austria. In 2022, tests conducted by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory at Natel’s Oregon project — a 1,070 MW, single-turbine installation along a major fish-populated irrigation canal — demonstrated greater than 99 percent safe passage of 186 large rainbow trout through the installation. In 2021, an evaluation of Natel’s installation at Freedom Falls Mill in Maine demonstrated greater than 99 percent safe passage of 484 juvenile alewife, a species of migratory herring native to Maine rivers. The Freedom Falls Mill was first built in 1834, proving that even the oldest hydropower projects can be retrofitted to meet 21st-century standards of sustainability.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Currently, Natel is developing two more major projects: turbine installations on three existing non-powered dams in Louisiana, and the first in a series of 33 potential installations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a country where 90 percent of the population lives without access to electricity.

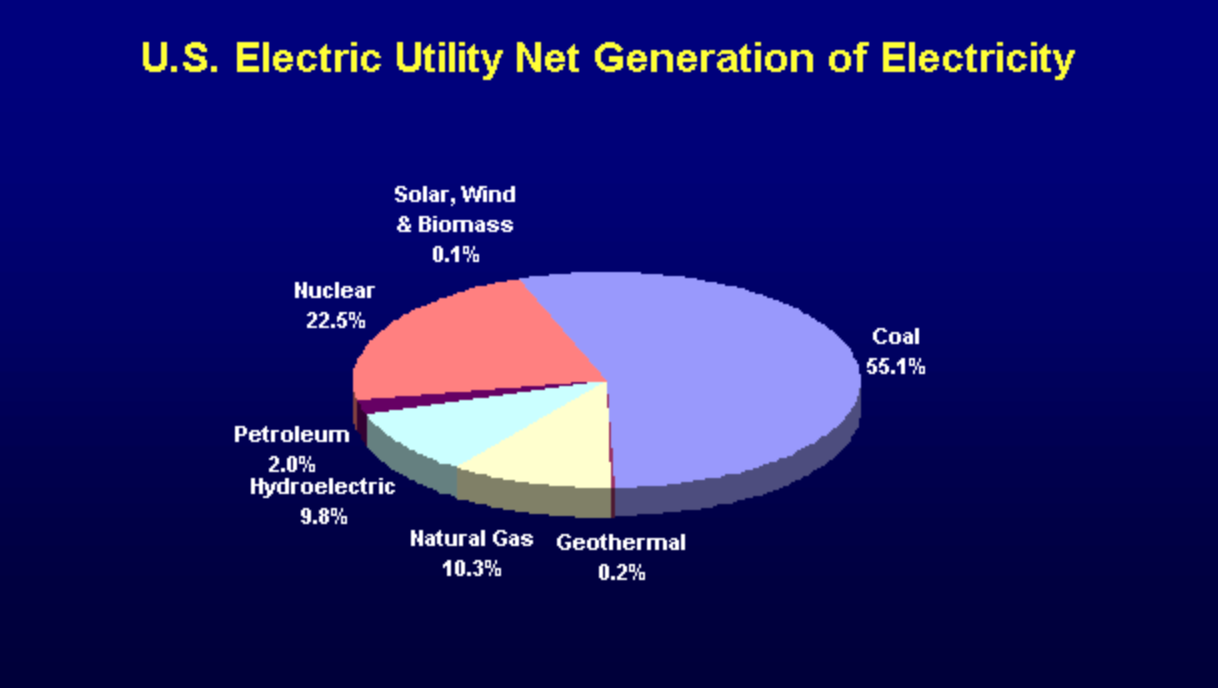

Today, renewables account for a fifth of all US power generation, and hydropower accounts for a third of that share, smaller than wind but higher than every other renewable source combined. And though age-old hydro has lost some of the limelight to rapidly cheapening solar and wind, its importance in a low-carbon future has not diminished.

For one, hydro offers something wind and solar largely can’t: stable, “baseload” power. “It’s a cliche at this point, but there are times of the day when wind isn’t blowing, when the sun isn’t shining, so how do you get renewable energy during that time?” says Shannon Ames, executive director of the Low Impact Hydropower Institute (LIHI), a New England-based nonprofit that inspects and certifies hydropower facilities, rewarding those that minimize or eliminate negative ecological impacts of power generation.

In certain states, certification from LIHI provides qualified facilities access to preferential green energy markets, where, according to Ames, buyers are increasingly looking for power that is low-emissions, ecologically sustainable, cheap and reliable. “Now there is a much bigger awareness of the role that hydropower can play,” says Ames. “That comes with a greater awareness of hydro’s impact, a greater desire to make sure that people in hydro are working to have the best ecological impact that they can.”

Though new projects like those in the DRC allow Natel to employ more holistic hydro design, opting for less-obstructive structures closer in design to beaver dams than concrete dams. Those projects, at least in the US, are a relative rarity. Domestically, Natel is focused on adapting its turbines to the needs of already existing hydro projects: retrofits and equipment updates.

“The reality of hydropower is that the vast majority of hydro here in the US and in Europe is already in place,” says Schneider. “So the biggest opportunity…is by making changes to what’s already there, not necessarily by building a whole bunch of additional hydro.”

There are some 1,500 active hydropower plants in the United States, along with tens of thousands of non-powered dams. And though these structures are unlikely to be rebuilt from scratch, they do have to be relicensed.

Nearly 40 percent of all currently active hydropower licenses expire in the next 10 years, with three-quarters expiring in the next 20. This impending wave of relicensing, to Schneider, presents an unprecedented opportunity to align the goal of generating clean power with protecting aquatic life.

“In many cases, owners are already investing in refurbishment or turbine replacement…but never contemplated the possibility that a turbine can pass 100 percent of fish safely,” says Schneider. “It’s critical to get the word out because there’s a real near-term opportunity to make decisions that will then get baked in for the next 50 years.”