“Hi, I’m sorry that I can’t respond to your email. I’m currently in a prison, recruiting more amazing colleagues for our business.”

That’s a standard out-of-office reply for Darren Burns, who, as director of diversity and inclusion for well-known UK service retailer Timpson, spends a lot of time interviewing candidates from within prisons.

CEO James Timpson made his first prison visit in 2002, during which he struck up a rapport with a young man named Matt. When Matt was released, Timpson offered him a job. Now, around 12 percent of Timpson’s 5,000 strong workforce across 2,076 branches either has a criminal conviction or has been directly recruited from custody.

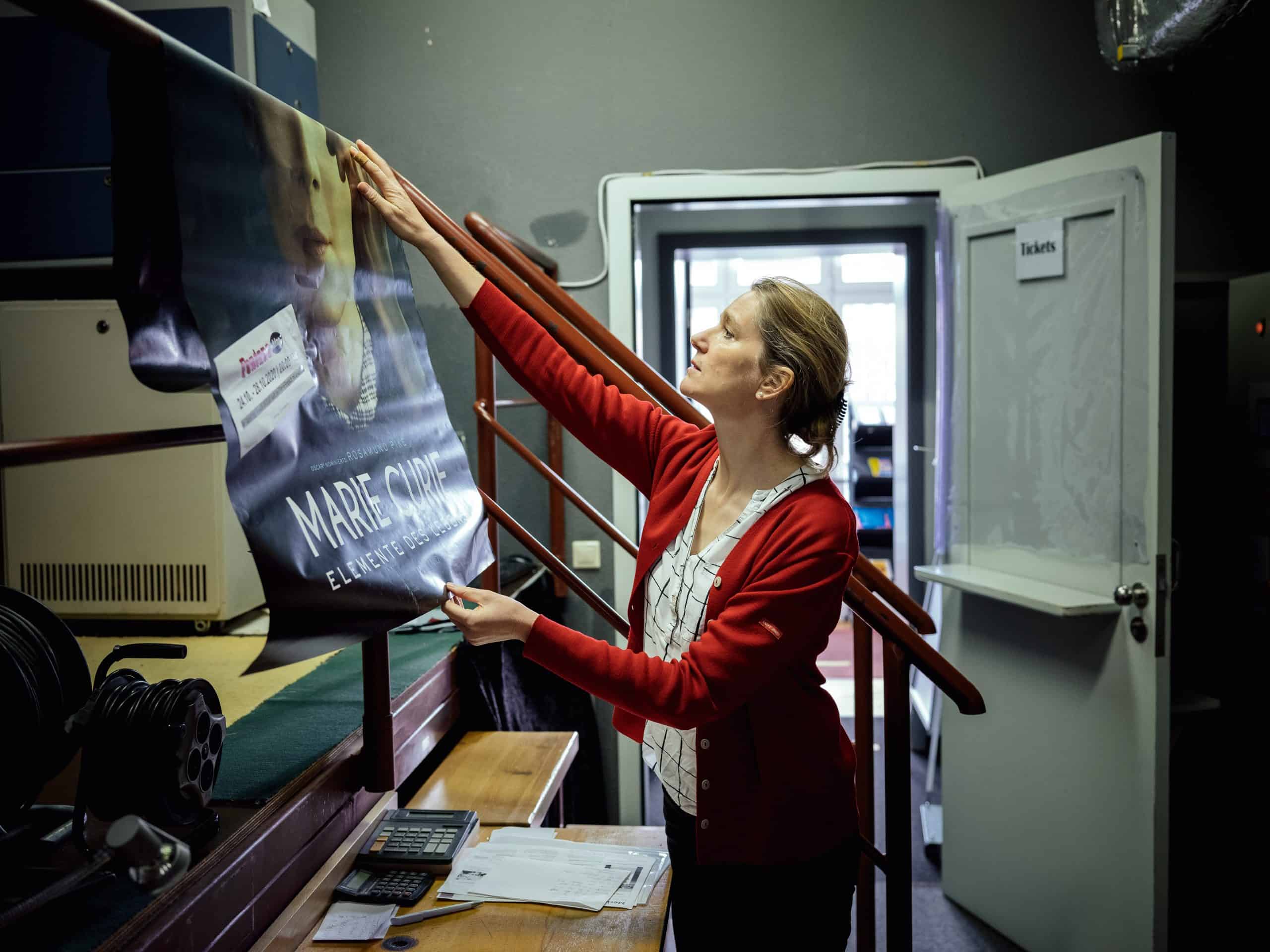

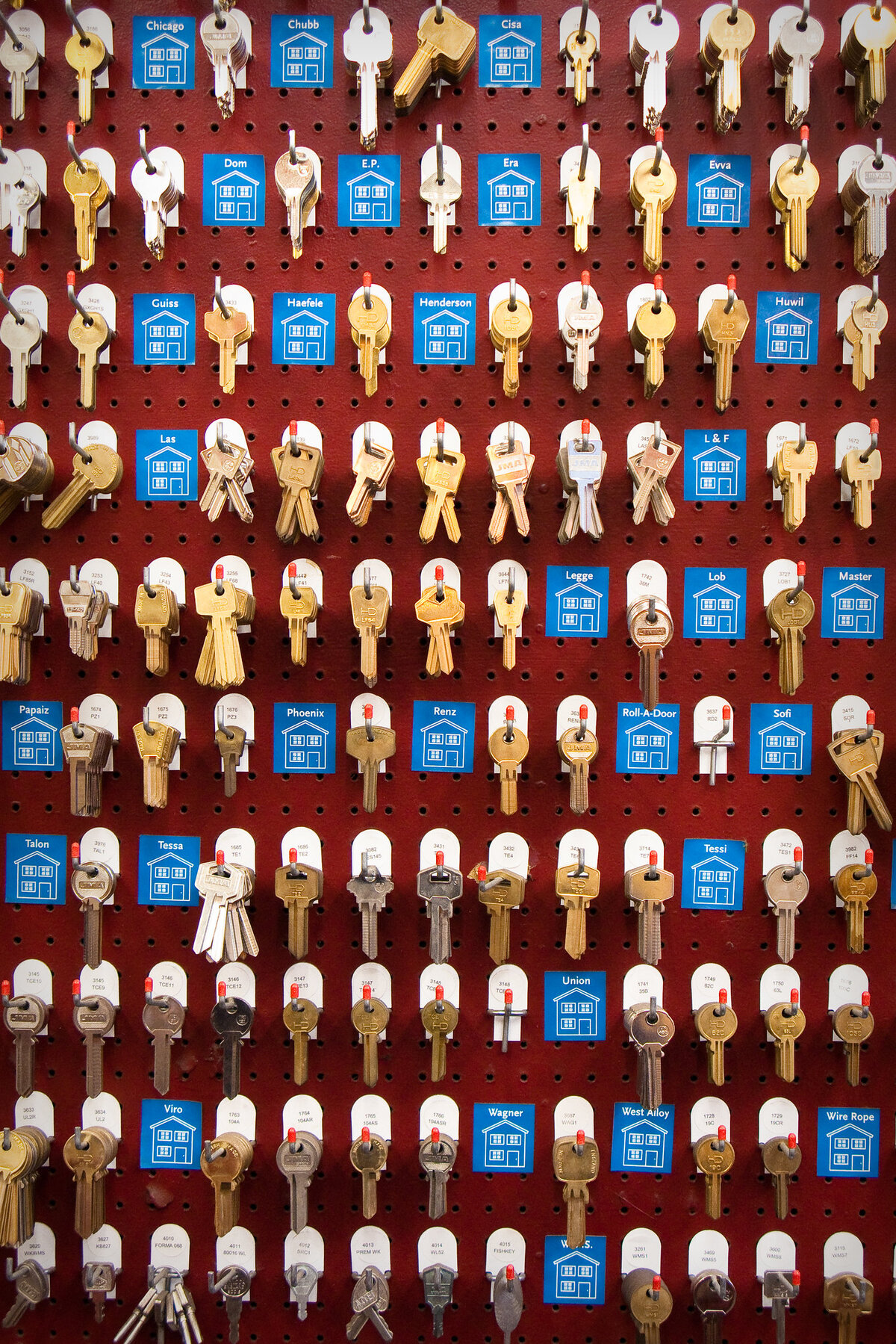

More than just your go-to outlet for getting your shoes resoled or new keys cut, Timpson has built a reputation for being one of the largest employers in the UK of not just ex-offenders, but of serving prisoners, too.

While you might expect that the ex-offenders and serving prisoners Timpson recruits would mostly be stereotypical white collar criminals, such as those who have committed tax fraud or other financial crimes — and some are — the workforce currently includes 16 people serving life sentences for crimes such as murder, who are employed as part of a day release program. Others have been convicted of crimes like theft, drug-related offenses and assault.

“Return on temporary license (ROTL), or day release, is the safest way to reintegrate somebody back into society following a long prison sentence. Because you think about the alternative — after years in prison, they open the door, get pushed out, and they’re pretty much on their own. Whereas we provide them with a safe working environment, and an opportunity just to get back up to speed with life,” says Burns. (Day release can be applied for in women’s open prisons across the UK, and men’s category C and D prisons. Open and category D prisons are considered minimal security, housing prisoners who have been risk assessed and deemed to pose little threat to the public. Category C prisons are focused on training and resettlement and are where most of the country’s prisoners are located.)

The Timpson brand has become so synonymous with ex-offender employment that it helped establish a UK government initiative to roll out Employment Advisory Boards across 91 prisons by next spring, ensuring prisoners have access to job opportunities — and the skills required — when they get out. The company has even set up replica stores within a number of prisons so inmates can learn the job in a real-life setting.

The £500,000 (around $636,000 USD) it cost to train ex-offenders joining the Timpson business last year is a small price to pay when you consider the cost of re-offending: according to the UK government, that cost is £18 billion (around $23 billion), and ex-offenders who find steady jobs within six months of leaving prison are nine percentage points less likely to commit further crime.

Employing the unemployable

Sarah Barker is one of Timpson’s biggest success stories. Barker was sentenced to prison in 2009 after stabbing a man who tried to attack her. She joined Timpson’s day release program in 2011, went full-time when she was released six months later, and is now a store manager.

“When we interviewed Sarah in prison, we really liked her and saw that potential. We met her at a particular point in her life where everything was grim and hopeless. We were able to offer something positive and be that first glimmer of hope she had, because at the time, she was thinking, ‘Nobody’s going to employ me because I’ve been in prison,’ so she didn’t have any sense of self worth,” Burns recalls.

“We’ve invested lots of time and effort in supporting Sarah over the years, and likewise, she’s worked very hard for us. She’s great with customers, and she puts lots of money in the till. To have someone like Sarah in the business, who’s experienced all sorts of negativity and trauma, creates a sort of figurehead that people look up to.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Burns also shares the story of a woman he interviewed in prison recently who is serving a five-and-a-half-year sentence for causing death by dangerous driving. She was driving her two young daughters home from ballet. When one asked what was for dinner, she turned her head to respond. In that split second lapse in concentration, she hit and killed a cyclist.

“She was a trainee accountant who’d never been in trouble with the police before. The fact that she is now in prison makes her largely unemployable to many organizations. To us, that just isn’t right. So now she works for us and she’s doing a really good job.”

Yet Timpson’s most senior ex-offender is Burns himself. He was also recruited directly from custody over 12 years ago, and like Barker, he started on the shop floor.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, where you’ve come from, how educated you are, what qualifications you’ve got, everybody starts off in a branch, making tea, coffee, sweeping the floors, repairing shoes, taking ID photos,” he says.

“I’ve now got a real understanding of what our colleagues on the high street go through and how difficult a job they’ve got. I’m very much there to support them to remove any barriers or obstacles that stop them doing a great job. They are the kings and queens of our business, because without them we wouldn’t have a business.”

Focusing on the future

While employing ex-offenders fits Timpson’s culture of “compassion and kindness,” Burns doesn’t shy away from the business benefits ex-offenders bring.

“What we realized long ago was that there are 14 million people in the UK with a criminal conviction more serious than a driving offense. And for us, it’s absolute madness to throw that huge swathe of the population on the employment scrap heap and assume that they’re worthless, dangerous and dishonest,” says Burns.

On the contrary, the people Timpson recruits from prison are loyal, honest and resilient – on top of being cheaper to recruit than people who come from traditional streams, Burns adds.

“We overlook past indiscretions and focus on what people can achieve in the future. If they can navigate [their] way through a long prison sentence, then anything that we throw at them as an employer, they can pretty much do standing on their head,” says Burns.

While Burns believes around a third of the UK’s prison population of around 88,000 is what he would describe as employable, Timpson can’t fix everyone, he clarifies. Offenses of a sexual, racist or homophobic nature are a no-go, as are terrorism-related convictions. People with severe addictions and mental health issues — prevalent problems inmates face — need professional support before they can be employment-ready, he adds.

That said, Burns confirms that in Timpson’s history of hiring ex-offenders, there have been few problems.

“People jump to the most extreme conclusions that everybody in prison is a dangerous, six-foot-four thug with tattoos or an axe-wielding maniac. And that is just not the case,” says Burns.

“Yes, these people exist, but they are in the minority. The vast majority of people in prison have made a bad choice or a series of bad choices, usually thanks to circumstances, and they just need a second chance.”