On February 29, 2020, seven men walked into the education building at Everglades Correctional Institution (ECT) as inmates. Three hours later, after passing a taxing Florida Department of Environmental Protection state exam, those same seven men walked out as certified Wastewater Treatment Plant Operators — with a promising career ahead of them.

The journey to that small classroom was not an easy one, but for hundreds of men and women in the Florida Department of Corrections (FDC), it has been rewarding. The prerequisites to the state exam are challenging: students must possess a high school diploma and pass tests in chemistry, microbiology and algebra through a California State University correspondence course on water treatment.

They’re able to do this because of a years-long effort led by currently incarcerated people at ECI to lead a wastewater class regularly attended by 60 people. It’s created an effective job pipeline into the green jobs industry with stability, high pay and benefits, all of which serve as important lifelines for people leaving prison.

“In the past it was hard to get a good job with a criminal record,” explained Sean Smart, a 45- year-old student serving a ten-year sentence at ECI. “Now that I’ve completed this course and attended the wastewater class, I feel confident about having a future career when I go home next year.”

Following opportunity

I first learned about water treatment by accident.

In 2015, before I moved to the Everglades Correctional Institution in Miami, I’d just started an eight-year sentence for burglary. After being hooked on prescription pain pills and hitting rock bottom, I knew that I needed to recalibrate my life.

I was searching for a purpose, anything that could help me thrive when I eventually got out. Even though I was laser-focused on personal growth and recovery, starting a new career at 45 years old was a constant worry.

Having been a hiring manager for several companies in the past, I understood the barriers in place for felons — most people just didn’t hire high-risk employees. If two equally qualified candidates were interviewing and one had a criminal record, we’d always discriminate.

One morning, I walked past an empty table in the TV room and saw an open textbook. The graphics and geometry immediately caught my eye, reminding me of my previous work at a civil engineering firm. The flow charts and diagrams and bell curves looked interestingly complicated.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.“Do you know what that is?” a voice asked from behind me. Eddie was friendly and spent the next half hour teaching me about water and sewers. “It takes some serious discipline to study inside here, but if you do these courses you can make a ton of money. And the treatment plants hire ex-cons,” he added.

I was intrigued, but not excited about a field with such a stigma — wastewater jobs seemed laborious and disgusting. Eddie was getting ready to get released, and since he’d been working outside at the prison’s small wastewater plant, he had a job lined up in Georgia when he got out. “Because I earned my license inside, I’m starting at $43,000 a year with full benefits,” he told me.

Over the next couple of years, I noticed dozens of men studying this same correspondence course — a devout wastewater cult who never shied away from telling others how good of an opportunity it was for felons.

I’d heard stories of newly certified operators leaving prison and finding work immediately. Staff members promoted the trade with zeal; someone always knew somebody who was working in the field and succeeding out there, making great money and getting promotions.

Finding a job when you transition back home is vital, but being able to start a career is monumental. Current research shows that there’s no shortage of new “green-collar jobs.” Federal data shows that wind turbine inspectors and solar panel installers are two of the top three fastest-growing jobs in the United States, with water treatment/conservation and sustainable agriculture close behind.

Water treatment is unique in the field as it offers state certification while still incarcerated. In addition to supporting the correspondence courses, ECI offers its own wastewater class that’s peer-facilitated by certified instructors and is regularly attended by over 60 students. “The numbers for the state exam are consistently high every year, thanks in part to this class,” Forrester added.

For those certified in this skilled trade, job opportunities are plentiful: treatment plants, environmental firms, public utilities, water and sewer maintenance, lift station mechanics, lab technicians and septic tank installers are all hiring men and women for the field.

Positions with a public works department can be lucrative and have room for advancement through “upskilling” (continually learning new skills). Many inmates I’ve served time with have been hired in the past as county workers in Florida and California, among other states.

An estimated 75 percent of certified treatment plant operators will find work with a city or county, and personal testimonies I’ve heard prove that many agencies are willing to give someone with a criminal background a chance at on-the-job training.

In fact, according to TPO Magazine, the demand for entry-level operators is so great that many government agencies offer these college courses for free to high school students — a public relations stunt necessary to bring attention to an essential field.

This is a fortuitous circumstance for ex-offenders who want to work, but are marginalized because of our past decisions.

According to Unlocked Futures, a prison reform nonprofit partnered with Grammy-winning artist John Legend, the unemployment rate for convicted felons in 2019 was around 27 percent.

Even though ex-offenders have paid their debt to society, the punishment can continue on indefinitely through bias and pre-screening background checks. For most, even when being honest about their past mistakes, a felony can mean never getting hired at a well-paying, respectable company.

Forced to take minimum wage service jobs that barely offer a living wage, or off-the-books gigs without worker’s compensation or benefits, the average person getting out of prison has lost before the game even begins.

“Many men leaving this institution face a big obstacle trying to find work,” Scott Siegler, ECI’s assistant warden of programs, shared with me in conversation. “Learning a new vocation inside makes that transition easier. The wastewater treatment course is our most popular class here at Everglades, and companies have proven willing to hire ex-offenders.”

Accomplishing goals

When I transferred to Everglades in 2018, I’d already made up my mind to pursue a career in drinking water treatment. It fulfilled my desire for a right livelihood in an environmentally conscious field that would challenge my intellect.

My family bought my textbooks and enrollment tests, and I started to study the applied science with vigor. I’d never had any trouble finding a high-quality job in the past, but I didn’t know how hard it would be when I got out of prison. I needed to become an asset.

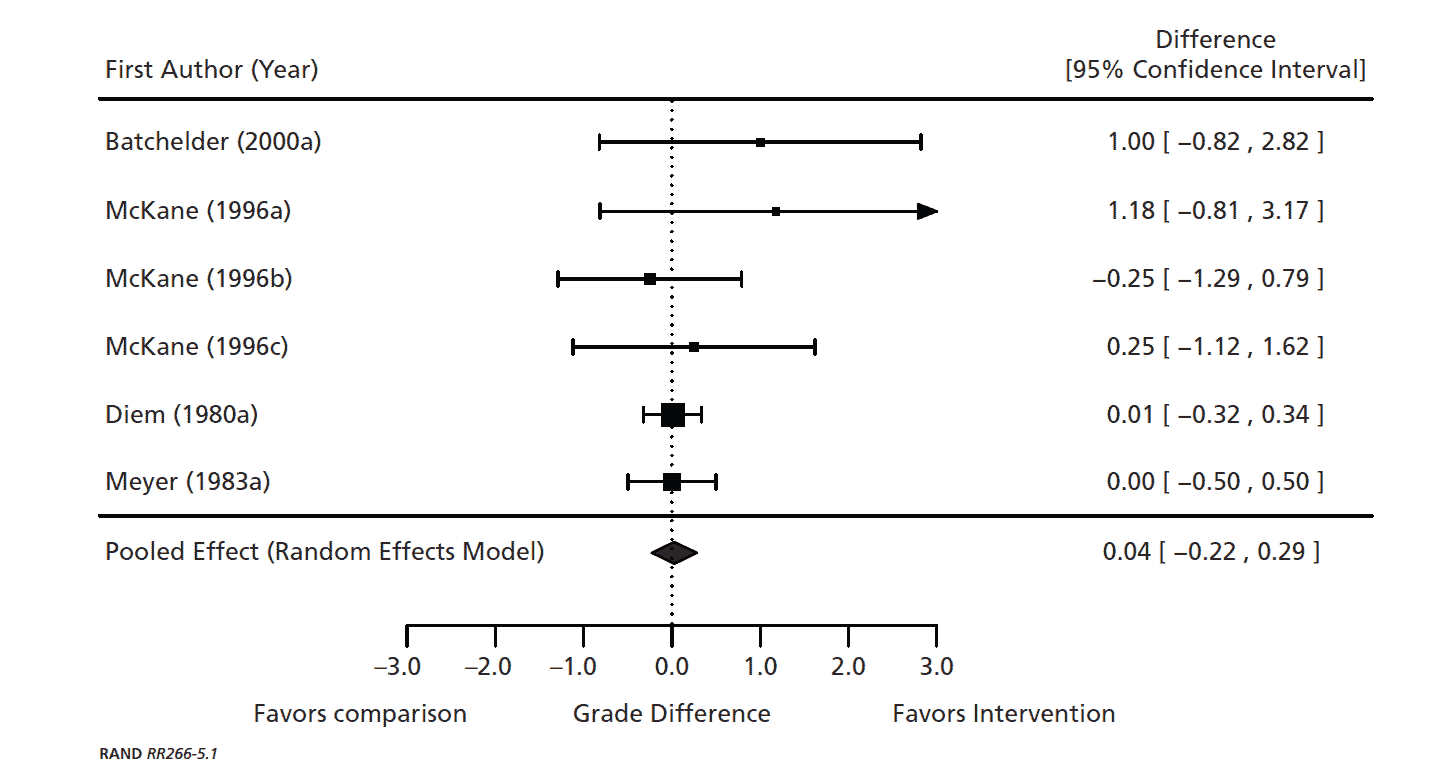

One RAND Corporation meta-study showed that inmates receiving vocational training inside are associated with a 43 percent reduction in probability to recidivate.

Training in the water treatment field is an opportunity to work in a meaningful industry and regain a sense of what it means to be included in a larger community again — to be a part of something bigger than ourselves. Essential workers are valued and appreciated, and that is something which people need after the demeaning experience of prison.

I wasn’t at ECI long before I discovered serendipity — they had a wastewater class being taught by a fellow inmate whom I’d already met. I enrolled in the class of 25 dedicated men, all following the same goal.

We studied straight from the California State University textbooks, compared notes about sedimentation tanks, asked questions about nitrification of microorganisms, memorized glossary words like turbidity and hydrogen sulfide. We agonized over algebraic equations.

Inmates from different backgrounds, gangs, neighborhoods, races and education levels sat side by side, unified in one cause and fighting for our future. This was normally unheard of in any correctional institution.

Studying in the dorm was filled with distractions — the class became my weekly moment of Zen for learning. Our peer-facilitator, Stephan Hearns, was enthusiastic, challenging us to pass the state exam like he had. “You will get this if you focus. I never went to school and I made it. If I can do this, you can too!”

I was his most loyal student, finding the giant Haitian man at chow and prodding him with questions. Harassing him on the rec field. Following a year of working as his aide, as Hearns was ready to go home after 20 years in prison for robbery, he pulled me to the front of the class one day. “This is your new teacher, fellas.”

I’ve been the lead peer-facilitator for the ECI Wastewater Operator Course for two years now, and I am one of those seven proud men who walked out of the education building last February as a state certified operator.

Now, in an empty visitation park every Monday and Friday morning, I stand in front of 60 men — rumored to be the largest organized wastewater class in the FDC — and teach my heart out, knowing that when I get released next year, I’m a part of the long legacy being left behind.

Roadblocks remain

In an op-ed last year, researchers with the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) noted that 70 percent of science, technology, engineering and math workers are white and 65 percent are male.

What does this mean for my last graduating class, who were overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic? What does it mean for men and women at other institutions across the nation, when over 56 percent of prison populations are minorities?

Furthermore, FDC statistics show that the average inmate tests at a sixth grade level. Even a task like earning a high school diploma can be daunting. According to a joint 2021 Brookings-AEI report, 30 percent of incarcerated men and women have no high school credentials at all. Add a rigorous college course that demands self-discipline and organizational skills that many disadvantaged prisoners have never been taught before, and the number of willing candidates diminishes.

ECI student Sean Smart described how hard it was just to restart his education. “I got my GED when I was eighteen. Twenty-seven years later, I had to relearn the basics just to take this correspondence course…and it wasn’t easy.”

Even in a progressive green industry filled with opportunity, there are still some limitations to how much an ex-offender can hope to achieve. Some plant supervisors are willing to hire those with a criminal background, but the local government that runs the administration might not be. Private contractors, deterred by insurance worries or judgmental attitudes, can say no without cause.

Maxwell Gottesman, a 60-year-old ex-offender who served 10 years in prison for a drug charge, was dual-certified in water and wastewater operations when he left ECI in 2017. When asked if it was hard to get a job as an ex-offender, Gottesman told me via email that because he had a nonviolent drug charge, it was easier to find a job than for some people.

“The number one concern for employers is the safety of their employees and the reputation of their business,” he wrote. “The Palm Beach County Water Utilities hired me knowing that I have a criminal record.”

“Right now there are more water treatment jobs available than there are operators to fill them,” Gottesman added. “But just because there are a lot of openings out here, that doesn’t mean they’re all available to ex-cons. Certain municipalities are very strict in their hiring practices, and the nature of a person’s charge has a lot to do with it.”

Mr. Gottesman is currently employed at a drinking water plant in Boca Raton and thriving after his incarceration, but unfortunately for many, his success story is uncommon when talking about jobs and life after prison. Although one out of seven Americans know someone in prison or on probation, many companies in this country still refuse to hire convicted felons.

The Brookings-AEI report stated that successfully reintegrating formally incarcerated individuals depends on increased access to occupational skills-based training inside prisons.

Building a skill base to meet the needs of the current labor market will significantly increase access to sustainable post-prison employment opportunities, and providing free books for water treatment training could be a starting point to lower recidivism.

In an email received by our wastewater class shortly after his release, my predecessor Stephan Hearns wrote:

I’ve been put on the waiting list for an entry-level position at Miami-Dade Public Works, but since I don’t have a driver’s license I can’t start just yet. At least they were willing to hire me. Take care of yourself in there and train well.

For a teacher who helped guide hundreds of ECI students toward a new career path, a job offer was the least that he could get. Now we look forward to the day when many more ex-offenders can say the same.

This story was supported by Empowerment Avenue, a program that supports incarcerated writers publishing their work in mainstream media. Follow them on Twitter @EmpowermentAve