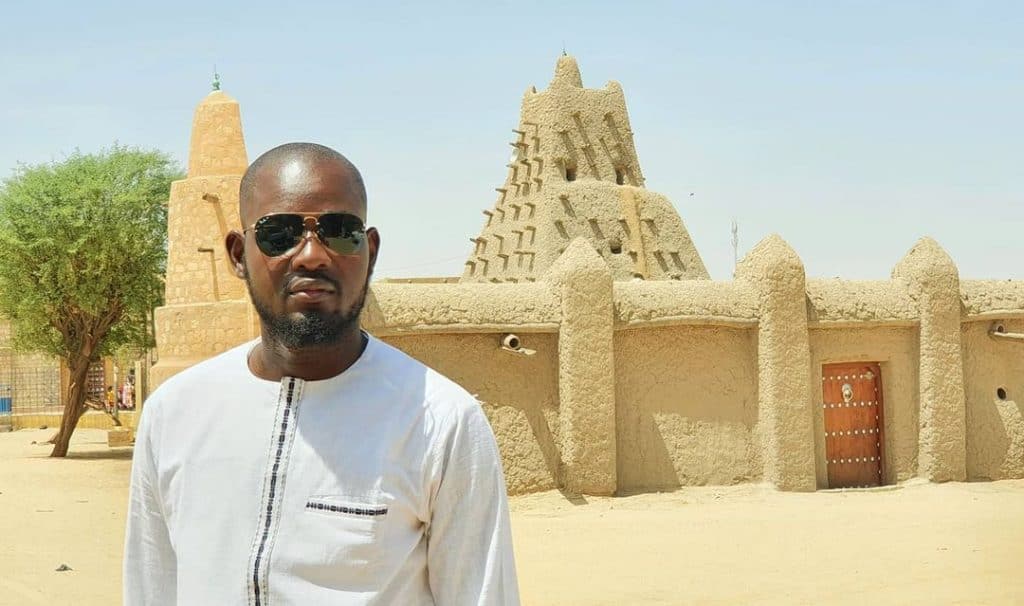

From the age of 13, Ali Nialy began working as a tour guide for the reliable stream of international visitors coming to his hometown, Timbuktu.

Straddling the edge of the desert in central Mali, the UNESCO World Heritage site — dubbed the “Pearl of the Sahara” — is famed for its spectacular mosque made of mud, ancient Islamic manuscripts and key role as a 14th century trading center. As many as 200,000 tourists once visited the West African country each year.

Nialy would recount the centuries-old history of his streets, lead camel-riding tours through the mythical landscape, and later branch out to the cliff-hugging villages of the Dogon ethnic group. “People came from everywhere in the world,” he says.

But in 2012, with the emergence of an Islamist jihadi occupation that kickstarted an age of violence and insecurity across the region, Timbuktu’s once-thriving tourist industry disappeared in the blink of an eye. The ongoing armed conflict means the northern half of the country, which includes Timbuktu, is a no-go zone for tourists. The US State Department and many international counterparts advise against travel to Mali, and Timbuktu has been added to UNESCO’s list of World Heritage in Danger.

“It’s such a horrendous situation,” says Lucy Durán, a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. “The impact has been devastating on local communities. With the instability and poor governance, a lot of nonprofits have withdrawn. The most peaceful country in the world has turned into a battlefield.”

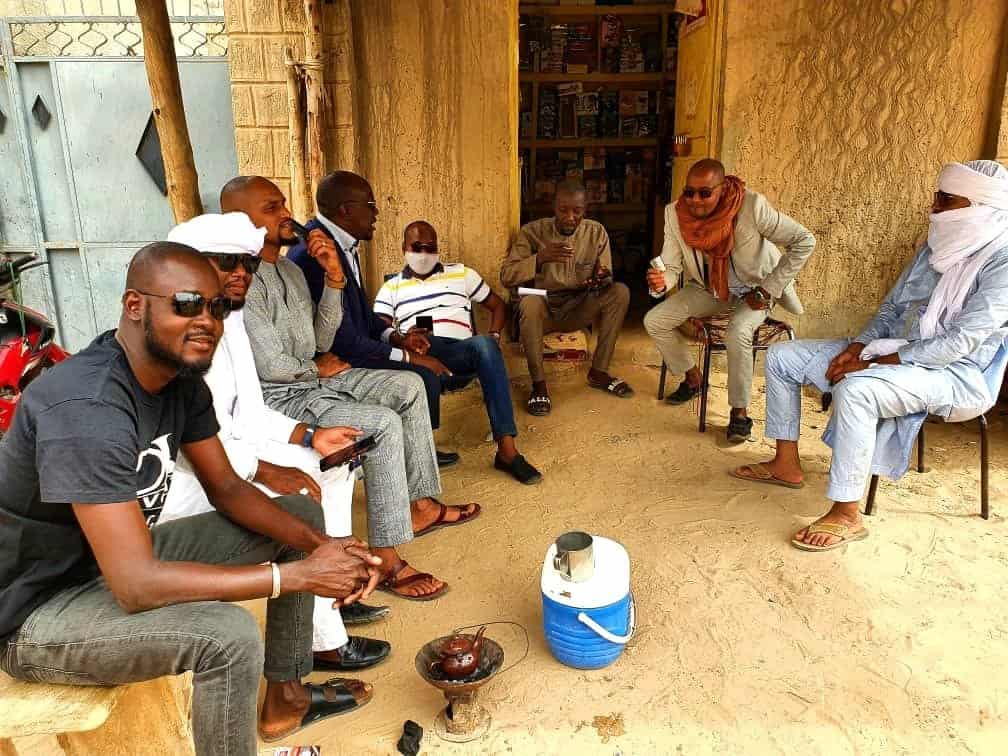

For years, Nialy and the other residents of Timbuktu saw their livelihoods drain away and slide towards ever-greater desperation. But in 2016, Phil Paoletta, an American owner of a legendary hostel in Mali’s capital Bamako, The Sleeping Camel, and Nialy, now 34, agreed on a plan to deliver the people of Timbuktu a new form of income.

The result was Postcards from Timbuktu, a project that cannily plays on Timbuktu’s image as a faraway land at the edge of the earth. Through it, customers can order a personalized, handwritten postcard sent from Timbuktu to an address of their choice anywhere around the world. The project allows would-be tourists to support these former guides, who remain deeply attached to their hometown despite the conflict.

“There’s people who contact the website, who think it’s a joke,” says Paoletta. “They think that Timbuktu is made up. But when these postcards arrive it really brings home that it’s a real place and real people live there.”

The mysterious allure of Timbuktu dates back many centuries, according to Durán. Many European explorers tried to reach the city, she explains, but in 1827 French explorer René Callié was the first to visit and return alive.

“Reaching Timbuktu was this impossible feat, like going to the moon,” says Durán, who first visited Mali in 1986 and has returned almost every year since.

For Nialy, however, it is the people who make the place special. “Timbuktu is a kind of mixed country — there’s Berber, Arabic, Songhay and Tuareg people,” he says. “But everyone here treats you like brothers and sisters. They share everything.”

The company has sent out more than 7,000 postcards to date to countries in Europe, the United States, Latin America, Asia and neighboring African countries. Each card costs $10, with the guides earning between $2 and $4.50 per card written and sent — the rest goes to printing and postage costs and taxes. With the average monthly salary in Mali around $100, it is a significant amount of income for straightforward work — even if demand is not always reliable and tends to fluctuate over time.

“It is big for us, it helps the families survive,” says Nialy, who is now working as part of a team of more than 20 people. And that money trickles down through the local economy in Timbuktu, where he estimates half the population is now unemployed. “Myself, I use the money for my family. It helps me to feed them.”

Likewise, Durán, of SOAS, gives her stamp of approval. “This project could do a lot of good — they are in desperate need,” she says. “But there’s a long, long way to go before the people of Timbuktu can live as they did before.”

The inspiration for the project came after Paoletta, who is based in Bamako, received mail from a friend in the United States, the first delivery he had received in six years. He called Nialy, who he had worked with through previous guide work with shared clients. “Phil called me and said, ‘Why don’t you do this? Maybe you can survive and find work for the rest of the guides,’” recalls Nialy. He then contacted Timbuktu’s post office to see if it was still operating and gave it a test run. When that worked, Nialy began organizing the guides and liaised with Bamako’s post office.

Senders have a choice between vintage images of Timbuktu, drawings or photos by local artists such as Timbuktu’s last master calligrapher, Boubacar Sadeck, or even a design colored by pupils from the local elementary school. On the back the guides faithfully write the messages — some people write love letters to partners or motivational letters to themselves, and others pretend that they themselves have actually sent the postcard from Timbuktu. Most arrive at their destinations in two or three weeks, but some take much longer, and every now and then, a postcard gets lost. In some cases, that’s even resulted in them being labeled scammers.

“There were some hiccups, and there still are now,” says Paoletta. “We try to convey that to people when they are ordering items. There’s a serious unpredictability to it.”

That unpredictability can be part of the allure. Each postcard goes on an incredible journey: from Timbuktu’s tiny post office, it is usually loaded onto a United Nations flight headed to Bamako, or sometimes it is down the Niger River by boat, or in the back of a 4X4, via the city of Mopti first. From there, the airmail almost always makes its way to France, due to its historic links with Mali, before traveling onward, sometimes with several more stops across the globe, before ultimately landing in the mailbox of its intended recipient.

“Most people aren’t used to getting physical mail anymore,” adds Paoletta. “They send photos on Instagram, Facebook or WhatsApp. But with these postcards, you can order this item, and once you start it’s the beginning of a long process. You can’t track it. You don’t know when or if it will arrive.”

Beyond the promotion of slower living, Postcards from Timbuktu has potentially found a way to circumvent the barriers usually posed by violent conflict: it allows income to flow into local communities, perhaps providing a model for others to follow. A contact in Agadez, Niger — another place that has suffered from the collapse of the tourism sector — has gotten in touch with Paoletta to discuss the launch of something similar.

“This same project could be done in all sorts of places,” says Paoletta. “Places that have become inaccessible for whatever reasons. It could be a lifeline for them.”