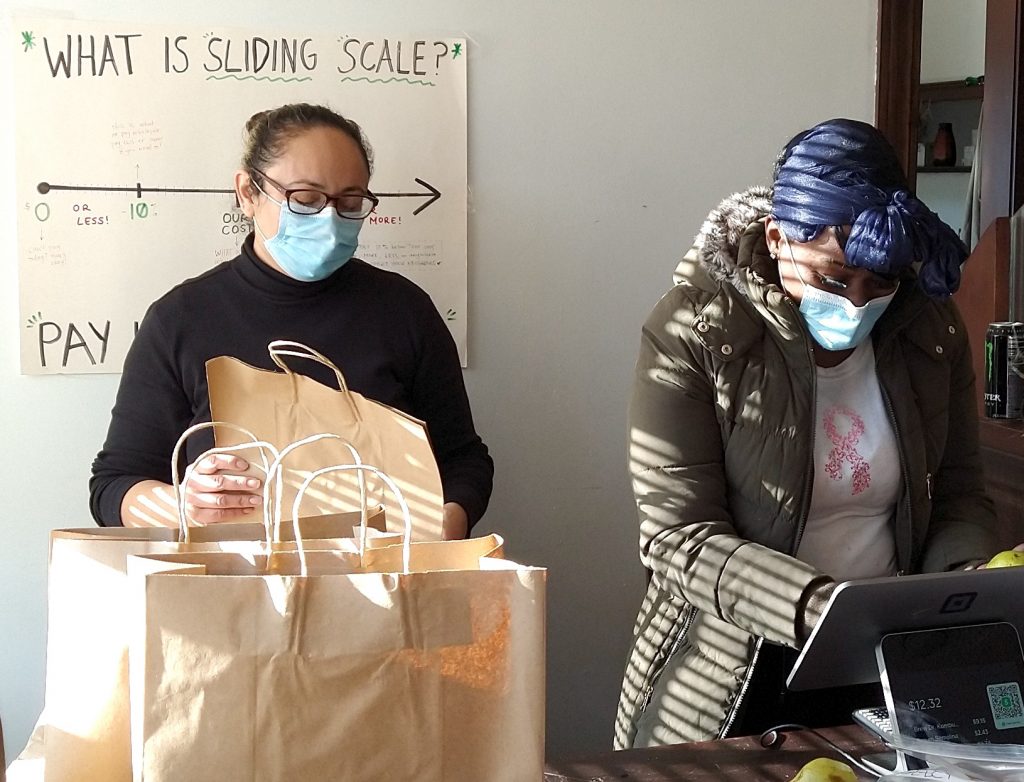

At MARSH Grocery in St. Louis, fresh bunches of asparagus, zucchini, and at least 30 other vegetables and fruits come straight from the food cooperative’s urban farm lots — and shoppers pick their price. The store, which opened a year ago to fill a gap in affordable, healthy food access in the Carondelet neighborhood, sells produce and a full range of other groceries on a sliding “pay-what-you-can” scale. Patrons can choose to pay up to 20 percent more or 20 percent less than what’s on the sticker.

Nonprofit grocers are notoriously challenging to make work but, MARSH founder Beth Neff says, their approach mostly breaks even, with above-price payments nearly matching dollars lost to discounts. “People who can afford it are very interested in adding,” Neff says.

According to the USDA, in 2021, 13.5 million US households experienced food insecurity, meaning there were times when there wasn’t enough money to feed everyone in the family. MARSH’s formula could be a piece of the puzzle in overhauling the food system to end hunger — a goal to which the Biden administration recently committed $8 billion. Indeed, a Brookings Institution report last year cited small grocers, along with farmers’ markets and community gardens, as a critical resource of healthy food access in many communities.

In the mix with the grocery store and three neighborhood farm lots at MARSH (which stands for Materializing and Activating Radical Social Habitus): a consumer-supported agriculture (CSA) program that delivers produce and prepared foods, a 24,000-item online catalog, a community event space, and a commercial kitchen that creates prepared foods for the store and the CSA.

Longtime neighborhood resident Laura Belarbi, 55, appreciated MARSH’s online system during the pandemic and now frequents the store for produce, bread, eggs and flour, as well as prepared foods like spicy lentil soup and empanadas.

“MARSH became a way to shop online and feel safe, and I really loved that because I was taking care of my mom,” she says. “And the store is close to home. I can run in and get something super-healthy and locally sourced.”

Belarbi, who works as a landscaper and considers herself somewhere below middle-income, says she pays above-price when she can and sometimes takes the discount. She’s also seen what the store means for others. “One of my neighbors doesn’t have a car, so she was thankful. Without the store, she wouldn’t have had enough to eat for a while.”

Healthy food, fair wages

Fifteen months in, Neff can tick off a host of small triumphs. In October, the store had 347 shopping transactions, and they’re seeing more repeat customers. The CSA met its target of 35 subscribers, whose advance food-box purchases lend crucial bottom-line support. The kitchen is busy 60 hours a week filling a higher-than-expected demand for nutritious prepared foods. Five staff members earn $18 per hour.

The co-op has 225 members, who join by paying (all or part of) a $100 fee or shopping 10 times at the store. The store is open to all, but members can access the online catalog and participate in store decision-making.

Still, making healthy food affordable to all while creating living-wage jobs is a lofty goal and a tricky balance. The money MARSH takes in does not yet cover its costs. As with other nonprofit groceries around the US, a lifeline of external support, mainly grant funding and volunteer hours, is necessary to stay afloat.

A spirit of experimentation helps too. MARSH’s sliding scale was at first nearly limitless. “Our price on the shelf reflected a 12 percent markup across the board — which was what we needed to break even — and then people were allowed to pay what they could, with a suggestion of up to 20 percent above or 20 percent below,” Neff says.

Given this freedom, many shoppers didn’t pay for food at all.

“We ended up giving away more than $10,000 of food in our first few months,” Neff says. “We couldn’t survive that way.” They had to tighten the rules for the 20 percent discount limit.

Samantha Mosier, a political science professor at East Carolina University who studies sustainable agriculture and food policy, finds none of this surprising.

“Even big-name stores face challenges staying in business. Often, profit margins are thin even where a store may have the ability to purchase at a higher volume,” Mosier says.

Nonprofit operations can fill voids in the food access landscape, Mosier says, often reducing the distance people must travel for healthy foods, providing more foods suited to cultural or regional cuisines, and creating a sense of community. But, she says, “the risk will always be there for financial instability, given the nature of the industry.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.For-profit grocery chains often shy away from lower-income neighborhoods even when a city offers financial incentives — or they arrive, force out existing smaller stores and then pull out, leaving communities worse off than before. Awareness of these risks is spawning experiments with alternative community-focused food solutions like MARSH across the US.

The Biden administration’s push to end hunger in the U.S. by 2030 allocates money for a range of actions to improve food access — though the list skews more toward support for private business and donation efforts than for nonprofit food stores.

Meeting a demand

Neff bought the vacant Broadway Street building where MARSH Grocery operates in 2018 after selling a five-acre farm in Indiana she had operated for 30 years. Her original vision was to reinvigorate what was an abandoned diner, but in spring 2019, historic flooding on the nearby Mississippi River dashed those hopes and led to a year of repairs and infrastructure replacement. So Neff focused on the food co-op.

For starters, her daughter created an online sales system for produce from the garden plot. The first online order came on March 20, 2020 — just as COVID-19 shutdowns began. That same day, they were approached by a local resident organizing a mutual aid effort to link food distributors and drivers to bring food to people in need.

“Over the next six months, we were distributing 100 food bundles per week for people who were homebound or sick and didn’t have food,” Neff says. They also started an outdoor market. These efforts brought MARSH visibility and helped them find local workers when they were ready to hire.

Seeing the local food demand, Neff successfully applied for grants from USDA’s Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program to add farm plots, and from USDA’s Healthy Food Financing initiative, which aims to enrich options in food deserts with limited grocery store access, to establish the storefront grocery co-op.

Tackling hunger

Grants are key for survival, but as for many fledgling nonprofits, short-term funding cycles pose a challenge. When the initial grants ended in early 2022, MARSH had to reduce staff and store hours.

“One-year grants are certainly not the solution to tackling hunger,” Neff says.

Having a diversified operation has helped. The CSA has been “a lifesaver,” Neff says, and in working to meet prepared-food demand, they’ve discovered ways to reduce food waste, helping to cut costs.

“Every single item — misformed vegetables, dairy that’s about to go out of date — is transformed into other products,” Neff says.

The store isn’t yet serving a full spectrum of area residents, many of whom are struggling with poverty and addiction. The staff is planning a door-to-door canvassing to get the word out to more neighbors.

Neff has secured a new two-year grant for growing food and researching farming strategies for a warming climate. She still has her eye on opening the diner, which she believes could help support MARSH financially and create more jobs. And as it grows, she hopes to formalize the operation as a worker-owned cooperative.

“It feels like exactly what I hoped for, that we would create connections between relational economy, sustainability, climate resilience, community building, quality of life,” she says. “Even if we don’t yet sell enough food to say we made money at the end of the day, we’re certainly creating a foundation for those things.”