Neon yellows, soothing blues, and revitalizing greens: the average supermarket aisle is a riotous, colorful battle for a customer’s attention, according to Dr. Brian Cook, a senior researcher at the University of Oxford.

Every aspect of a food product’s packaging is designed to trigger specific emotions, sending persuasive information — whether true or not — to the brain. “But almost never does that information tell you the environmental impact of that product,” says Cook. “There’s a lot of noise but little fact for consumers. That needs to change.”

Cook, who leads Oxford’s Health Behaviors team at the Livestock, Environment and People (LEAP) project, believes that a tried-and-tested system has the potential to transform the way that we eat: labeling.

Just as labels showing a food’s dietary content or place of origin have helped improve our understanding of nutrition and ethical sourcing, Cook says a similar system could be used to combine a range of ecological indicators — from greenhouse gas emissions to water use — to show a product’s environmental impact.

During the pandemic, Cook’s team conducted an experiment in which “customers” were given fake money to select from 20,000 supermarket items. Each had a label showing that product’s ecological impact, based on four indicators: greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss, water pollution and water use. The result was a “statistically significant” shift towards ecologically greener foods, including around a 10 percent reduction in meat consumption. “It proved to be effective,” he says.

Now the next step — real-world testing — is underway. In May, the team launched a trial of the labeling system with the U.K.-based food services business Compass Group at 13 of its cafeterias. They found the most effective design was a globe symbol colored green, orange or red with a letter in the center from A to E, to signify the eco score of the food — a vegetable soup, for example, was rated A, while a lemon, spring onion, cheese and tuna bagel was given an E. Early next year, a second trial is planned across Compass Group’s office spaces and university sites with the researchers looking to see the impact on a younger, more educated demographic.

The efforts speak to a wider appetite for a label-led change in diets that is spreading across Europe. The NGO Foundation Earth will launch a trial of a traffic light-based label system in U.K. and European supermarkets such as Tesco and Morrisons this fall. And in 2024, the European Commission is set to propose an EU-wide scoring system as part of its “Farm to Fork” strategy. Meanwhile, in France, some businesses have already been using an eco-score label for almost a year.

It comes after the French Ministry for Ecological Transition (ADEME), which evaluated the environmental impact of 2,500 categories of products and published its findings in a free, open-source database known as Agribalyse last summer, launched a design competition for a national eco-score label. The winner is set to be announced early next year.

“When you consume a steak, you should know the environmental impact of it,” says Lucas Lefebrve, co-founder of French online organic store La Fourche, which rolled out the eco label for its store-brand products using the database in January. “We need to help and encourage consumers by giving them good information.”

Since then, Lefebrve says there has been an increase in demand for meat alternatives such as seitan, which have better eco ratings than real meat. “The impact of the labels is already tangible,” adds Lefebrve, who says he is in negotiations with French, Belgian and German distributors to introduce his form of label.

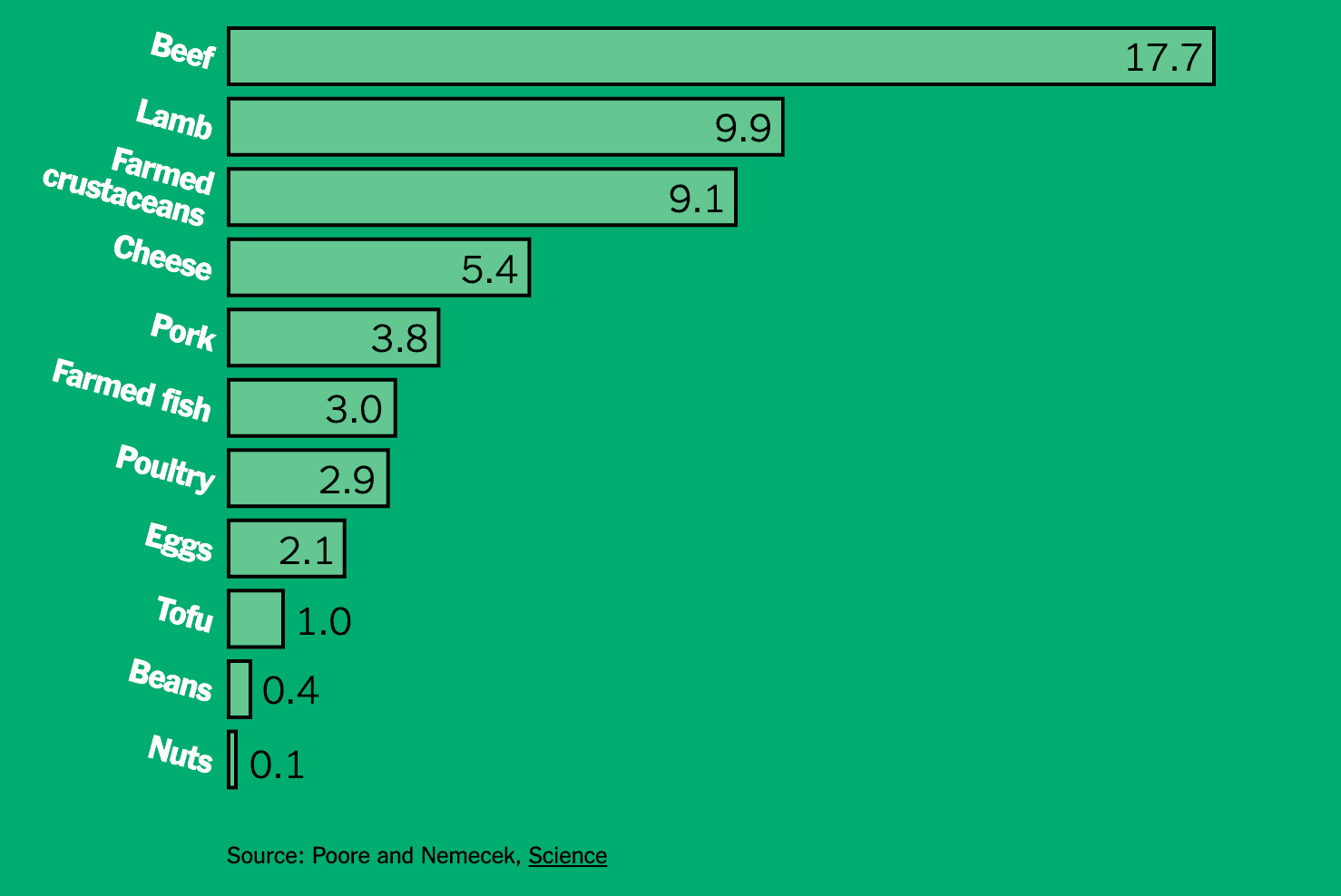

Proponents say that while radical institutional change is key to halting irreversible global warming, eco labels aren’t mere crumbs in the grand recipe of the climate. Food production is responsible for a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions. And research by WWF and the environmental consultancy ECO2 Initiative has found that we can cut our individual emissions in half simply by changing our diets.

Even switching between seemingly similar foodstuffs could have a huge impact. Dr Cook cites research from 2018 that found the environmental impact of beef could vary 18-fold depending on how it was produced. “You only need to be able to nudge 25 percent of the population from E to B or C and that could have a huge impact,” he says.

Polling suggests that a shift in behavior is likely if better information is provided to the public. According to polling by Elementar UK, 68 percent of respondents said the origin of food is either “very” or “quite” important in influencing their shopping, but 25 percent said they were “unsatisfied” or “very unsatisfied” with the information they are given.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Anna Cohen, agriculture lead at France Nature Environnement (FNE), an NGO that provides consultation on eco labeling to companies, says the example of Nutri Score, a labeling system based on nutritional values that launched in France in 2016, has shown the concept works. “It can create a more sustainable agriculture network,” says Cohen. “The labels can help people make their decisions.”

But Jean-Pierre Schweitzer, policy officer at the European Environmental Bureau, which reviewed two French initiatives, Eco-score and Planet-score, warns that deciding on a methodology for scoring could be more complex than it seems.

“The devil is very much in the detail of how the score is calculated,” he says. “It combines quantitative and qualitative information. Who decides what is important? It’s a political issue. And what if we don’t have real data but only estimates?”

The scoring system could produce some eyebrow-raising, though informative results. According to experts, a banana imported by boat from Colombia, for example, could have a better score than an out-of-season tomato grown locally in a greenhouse. And while the health benefits of almonds are well-known, its water requirements — growing a single almond requires 1.1 gallons of water — could saddle them with dismal scores.

Dr. Cook accepts that numerous challenges lie in wait. What works on a website might not work in a bustling city restaurant or sprawling supermarket. Another challenge is striking the right balance between the information being detailed, effective, and convincingly reliable. Calculating scores for products could prove a gargantuan task too — and would require political will.

But he believes the past success of labeling schemes shows these obstacles can be overcome. “In the grand scheme of the climate, it’s a low hanging fruit [in terms of action that we can take],” he says.