Thirteen-year-old Michael Weilert did everything just as his mother had taught him. He pressed the button to activate a blinking pedestrian signal at Pacific Avenue in Parkland, Washington. He waited until the first car stopped at the intersection before entering the crosswalk on his bike. Then, a young woman in a Jeep Wrangler failed to yield and struck the boy, killing him.

Here is the sad truth: Crosswalks don’t work. According to various studies, only between five and fifteen percent of drivers slow down at pedestrian crossings. The vast majority of drivers simply don’t pay attention to them.

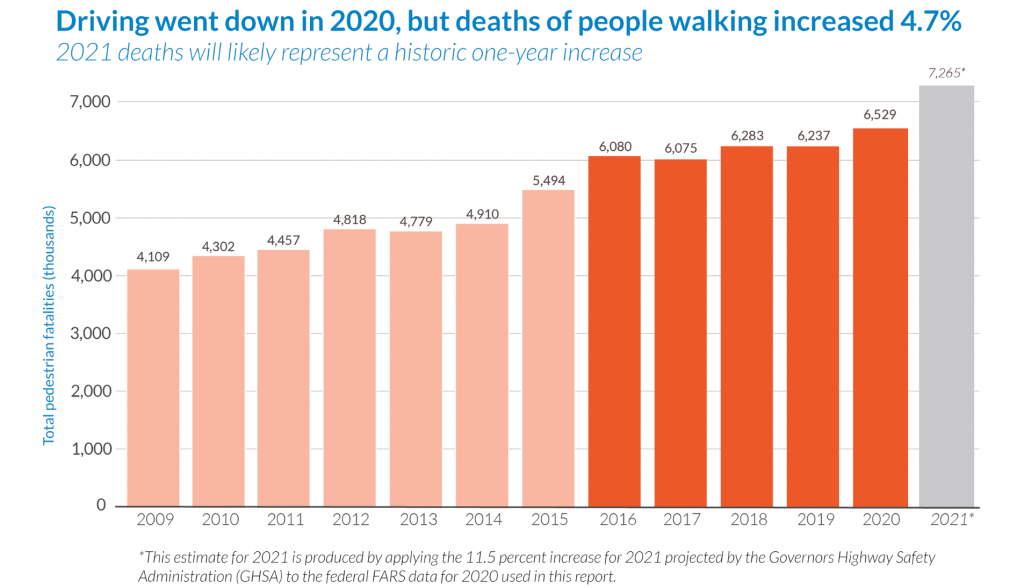

Given their ineffectiveness, it’s surprising that city planners rely on these unassuming white stripes to keep us safe from cars — particularly since America’s streets just keep getting deadlier: 42,915 people died in traffic crashes in 2021, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, a 16-year-high and a 10.5 percent increase from 2020. The risk for pedestrians keeps rising even more, with an unprecedented year-on-year rise in deaths in 2021.

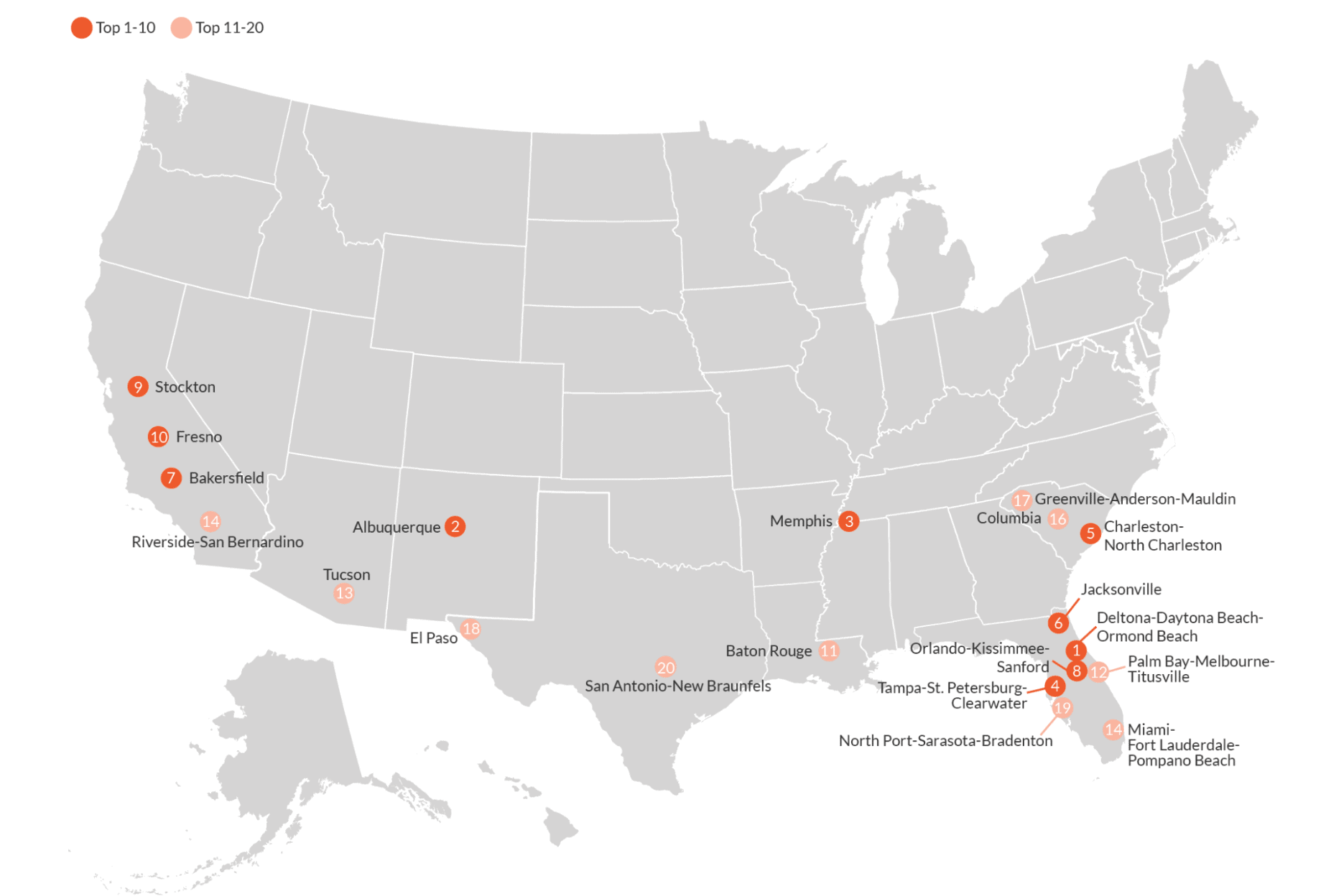

These deadly collisions are worst in low-income communities, which are less likely to have safe sidewalks, street crossings or recreational walking areas. A recent report titled “Dangerous by Design” by the Washington nonprofit Smart Growth America, which advocates for equitable urban planning, mainly blames the way those roads are designed — which is to say, for speed, with wide lanes and scant pedestrian infrastructure. A simple truth is: The wider the lanes, the higher the speed, and US cities have plenty of wide lanes that invite drivers to hit the pedal.

America’s deadly streetscape is the subject of The Street Project, a new PBS documentary about citizen-led efforts to make streets safer. When filmmaker Jennifer Boyd started making it, she assumed distracted driving must be behind the alarming rise in pedestrian deaths. But as she soon learned, digital screens are less of a culprit than most people realize. “Less than one percent of pedestrian deaths involved portable electronic devices,” she found.

Instead, she discovered that two of the biggest factors are speeding and bigger cars. In a chilling demonstration, she lines up elementary school kids in front of a standard size SUV. It takes ten kids until the driver can finally spot their raised hands. “There is no doubt the rise of SUVs has had a huge impact,” Peter Norton, a professor at the University of Virginia who studies urban mobility, tells her in the documentary.

Picturing a solution

If speeding and visibility are the problem and crosswalks can’t stop it, color might. The Asphalt Art Initiative, a program funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, provides grants to create art to modify dangerous streets. One of these projects is in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where artists and residents transformed a high-traffic commercial thoroughfare with a block-long asphalt mural, while students marked safe walking paths in the area with stencils and wheat paste.

In Durham, North Carolina, residents chose a high-risk crossing in front of an elementary school for a makeover. Together, they created a vibrant mosaic of dots and a blue mural with colorful fish. “Our oasis,” as the residents called it, had a surprising effect. “Potentially dangerous conflicts between drivers and pedestrians crossing the street decreased by 30 percent, and the percentage of people who felt unsafe crossing fell from 85 percent to six percent.”

In Lancaster, California, locals designated a busy five-way intersection for an artsy redesign. With the help of concrete stain, they shortened the crosswalks by more than half, added over 3,000 square feet of new pedestrian space, narrowed car lanes and added a stop sign. The result got the drivers’ attention: The average speed at the intersection dropped by 20 percent, the rate of drivers yielding to pedestrians increased by 10 percent, and bike ridership increased by 12 percent.

Overall, according to the Initiative, “the data showed a 50 percent drop in crashes involving pedestrians or cyclists and a 37 percent drop in crashes leading to injuries. Intersections with asphalt art saw a 17 percent reduction in total accidents.”

Dozens of places around the world have treated their streets to similar forms of art therapy, including Boston, Oklahoma, Vancouver, Delhi, and several cities in China and Europe. In some cities, 3-D decals painted on the road create the illusion of raised roadblocks or children in the street. In Delhi, 20 streets now appear to be cut off by knee-high cement blocks — a sophisticated optical illusion. Ontario has experimented with painted potholes in the road to convince drivers to slow down.

The illusion works best in the first few weeks when drivers are surprised, then tapers off a bit when commuters get used to it. But even then, it continues to slow down drivers, according to the founder of Delhi Street Art, which painted crosswalks in Delhi, and a spokesperson for Transport for London. In Vancouver, a painted “Pavement Patty” dashes into the street, seeming to chase a ball on Delta Avenue between two elementary schools. Along with signs reading “In a rush at a school zone? Seriously?” the effect has slowed down drivers there as well.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=931_Fq65gl4

Despite these successes, the model faces roadblocks, not least of which is the U.S. Federal Highway Administration, which has a history of cracking down on communities for non-regulation crosswalk art. But this might be changing. The agency is currently revising its rulebook, and as part of those revisions, aims to “reinforce the primacy of safety for all users in the interpretation of design standards” and “make ‘Complete Streets’ FHWA’s default approach.”

A culture of blaming the victim

Colorful crosswalks may reduce vehicular violence one intersection at a time, but the broader problem is more difficult to tackle: most US cities prioritize cars. Even costly new projects, such as the 6th Street Bridge in Los Angeles, come up short in regards to pedestrian and bicyclist safety. Contrast this with many European countries, particularly in Scandinavia, that have redesigned their streets by taking space away from cars and designating lanes exclusively for people and bikes. Since Sweden implemented “Vision Zero,” an initiative that has since been adopted by other cities in Europe and the US, traffic fatalities there have fallen by half. Likewise in Norway, where, after five years of committing to safe traffic strategies, Oslo, a city of over 600,000, marked its first full year with no pedestrian or cyclist fatalities in 2019.

“Good design keeps people safe,” says Mikael Colville-Andersen, a Danish-Canadian city planner, in Boyd’s documentary. An avid bicyclist, Colville-Andersen has a suggestion: “City planners should be forced to ride their bikes to work every day for at least a month before planning a city.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.But in the U.S., urban planners and police tend to blame the victims. In Michael Weilert’s case, the crosswalk was equipped with a center island and signals on both sides of the road. The driver had ignored all the cues, and yet here is how Robert Reyer of the Washington State Patrol described the crash: “He all of the sudden appeared in front of her car, and she was unable to stop.”

So far, the driver has not been so much as ticketed because the trooper didn’t consider her driving reckless. “Charges would only be forwarded if there was a criminal offense, such as being impaired and killing somebody, or driving in a manner that is, basically, reckless,” Reyer said. “We could completely exclude both. There was no impairment, and there was no reckless driving.”

Meanwhile, Weilert’s mother is fighting to prevent more accidents where her son was killed. She is advocating for changes at the intersection and points out the obvious: that failure to yield at a pedestrian crossing is by definition reckless. “I can’t imagine knowing that someone is stopped at a crosswalk and you wouldn’t stop, too,” she told local TV station KIRO 7. “Just that behavior alone is reckless.”