In New York, where I live, whenever there’s a big holiday weekend, the traffic on Friday as folks leave town turns much of Manhattan into a hot, fume-filled parking lot. On those days, one can often walk faster than the traffic is moving. That may be the exception, but congestion in many cities has reached the point where getting around by car at certain times of day is almost not an option.

Folks who live in L.A., for example, simply rule out driving to other parts of the city at certain hours. (The old “nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded” problem.) These drivers have synced their lives to the ebb and flow of other people’s cars, a sad but logical response, since congestion costs Americans more than $1,300 per year and 97 hours of their time. When you consider than almost half of Americans would find themselves in a financial crisis if they got hit with a $400 expense, it’s pretty clear that car-based lifestyles in cities aren’t sustainable.

So why do we keep driving? The simple answer is, in some cities, many of us have little choice. The Barcelona Institute for Global Health says that 60 percent of urban infrastructure is devoted to cars. Years of prioritizing driving at the expense of walking, biking and mass transit have left many people no viable alternative to private vehicles.

The result is more than an inconvenience. It’s estimated that vehicle pollution accounts for 184,000 premature deaths a year globally, and collisions are responsible for 2.5 percent of all global deaths. When all is said and done, cars kill more people than tuberculosis, malaria, diabetes or HIV/AIDS. That’s a lot of incentive to do something, and more and more places are starting to.

Around the world, cities are trying a variety of tactics to reduce congestion and take back urban life from the rule of the automobile. The good news is, in some places it’s working, and where it is, there is less pollution, less congestion, less danger and less heat. (As a cyclist I know that it’s fully five degrees hotter next to traffic).

Reducing car use is good for health, productivity, urban livability and the economy. I was curious who’s trying it, where it’s working and why. There are a few different approaches, each with their own advantages and drawbacks.

Banning cars from city centers

One way cities are reclaiming streets is by banning cars from their core areas, often with an exception made for residents, taxis and delivery trucks (which, in the age of Amazon and Fresh Direct, can be a LOT.)

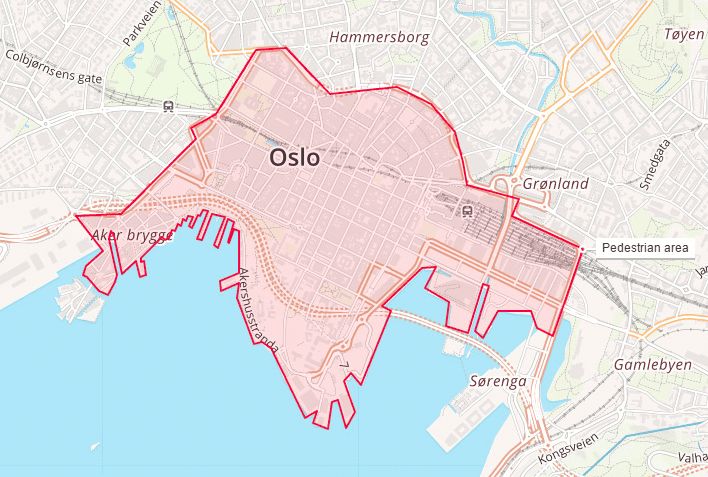

Below is the car-free zone in Oslo. While not 100 percent off-limits to cars, the city is succeeding at drastically reducing car use in this area, eliminating parking spots and banning cars on many streets. The car-free zone is part of a larger plan to make the whole city carbon neutral by 2050 (and this is in an oil-producing country!)

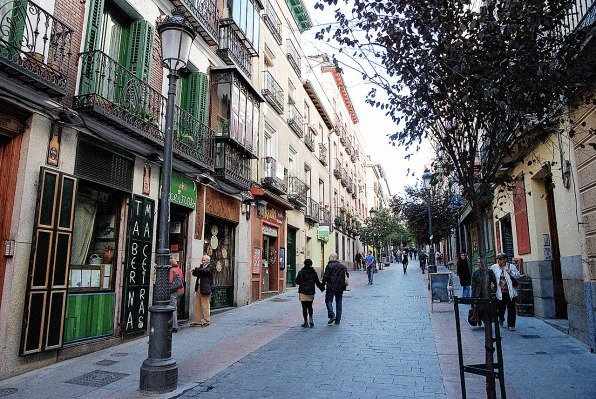

Madrid tried something similar over a year ago. They banned cars from the city center and major streets. Pollution dropped and safety improved, and the streets became a joy to walk. Imagine the street above filled with idling and parked cars. Who would prefer that? Well, apparently Madrid’s new mayor would—he rolled back the car ban, proving that political will is a key factor in any successful car-reduction initiative.

(Luckily, there’s another city in Spain that has dramatically decreased car use and kept it that way. Read about it here.)

In my opinion, banning cars from city centers makes for nicer, more livable places. But isolated islands of quality urban life, as charming as they may be, don’t solve the larger problem. So I’m encouraged to see that some cities are going step by step to end car use on a much larger scale, gradually making driving less relevant to residents so that someday they may have no cars at all.

Getting used to it: partial and incremental bans

A growing number of places have begun by giving their citizens a taste of what a car-free city would feel like. Bogota, for instance, bans cars from over 75 miles of streets once a week. Cyclists fill the streets and there are mass aerobics classes to cumbia beats.

Hyderabad, India’s tech hub, has experimented with banning cars from its IT corridor every Thursday. New York and Mexico City have both taken back major streets from cars periodically. (Just a few weeks ago, Manhattan banned cars from 14th Street, a major crosstown artery, and now buses move swiftly across the island.) Paris bans cars throughout most of the city for one day every year, and on that day nitrogen dioxide levels drop by 40 percent in some neighborhoods. But just one day?? To be fair, the city’s new mayor has championed street pedestrianization, banning cars along the Seine and, soon, around the Eiffel Tower, too.

Paris also banned older diesel vehicles this year and plans to ban ALL gas- and diesel-powered cars by 2030. This is indicative of a growing trend in Europe, where diesel cars are more common than in the U.S. Hamburg recently banned most diesel vehicles from two of the city’s key arteries, a move ushered through court by the environmental organization ClientEarth. Many other European cities—including Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Oxford and Stuttgart—are planning or implementing similar bans on diesel cars.

Congestion pricing

Other cities are focusing on making drivers pay to use city streets, a precious and finite commodity that, until recently, has been given away for free.

Congestion pricing, in which drivers are charged a fee to enter certain areas, has been pioneered by three cities: Singapore, Stockholm and London. Singapore was first (in the 1970s!) and it seems their scheme was both the cheapest to implement and the most successful. It is also the most flexible. Prices change automatically depending on how much traffic there is. Drivers are required to have an electronic smart card that is read when their car passes under a gantry. Taxis and ride-hailing services are NOT exempt, a crucial key to making it work.

The result is that congestion has gone down (along with pollution), drive times are faster and public transport use has increased. Singapore’s population is growing, however, and congestion is creeping back up to where it once was …but the system has been in place since the ‘70s, so they know it’s time for an overhaul and they can imagine what it would be like if no plan were in place.

Stockholm’s system launched in 2007 and was initially met with lots of resistance, but even delivery drivers have come to love it—their jobs are more pleasant and more efficient. The prices vary by time of day, and taxis and ride-hailing services pay the fees, too. Stockholm has good public transport, and commuters seem to be using it—even as the city’s population has grown, the number of cars that cross the congestion zone has remained steady.

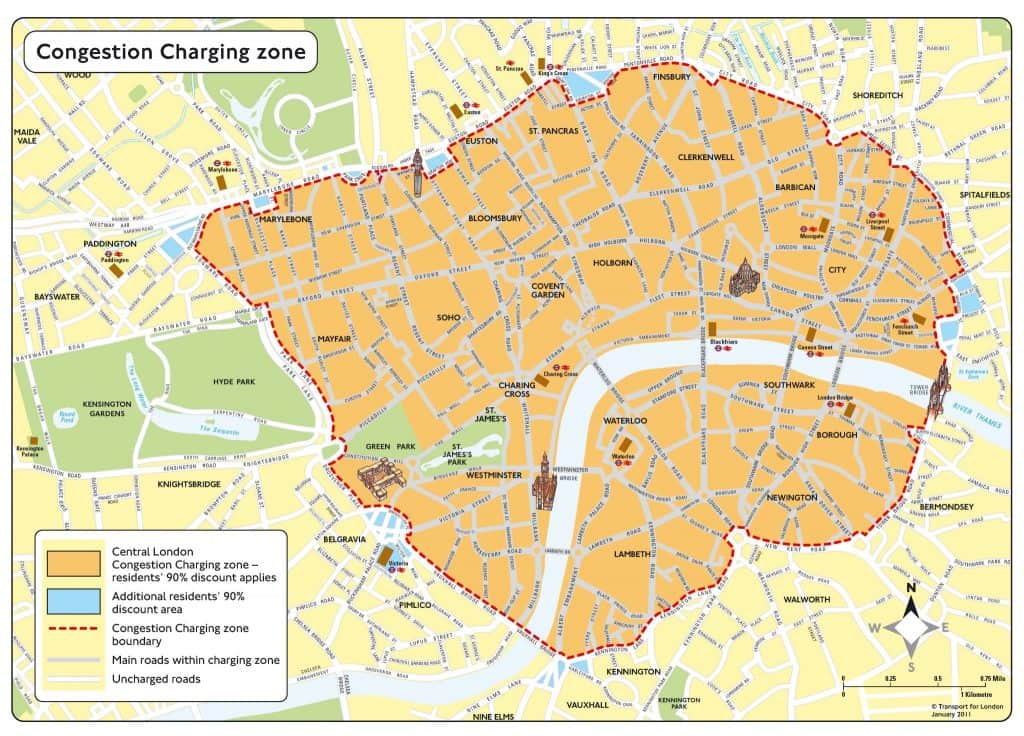

London’s system was very successful at reducing congestion initially, but in the time since it was implemented in 2003, traffic has crept back up, and now, by some measures, it’s worse than it was before congestion pricing began.

There are a few possible reasons for this. For one, until earlier this year, app-based ride-hailing services like Uber were exempted from London’s congestion fees. Uber, of course, did not exist in 2003, but now it’s everywhere. So are idling delivery vans, which block the twisty streets of London Towne. London charges drivers a flat fee, which also doesn’t work as well as the more flexible systems in Singapore and Stockholm. And most London residents are unaffected by the congestion charging zone, which only covers about 1.5 percent of the city.

Transport for London, the city’s transportation agency, claims that one of the reasons congestion has gone back up is because of the additional road space given over to pedestrians and bikes. Part of that is intentional. Making a city less car-friendly (by eliminating some on-street parking, for example) is meant to discourage driving in the city—a worthy goal. But even though London has bike lanes—notably its “cycleways,” which work pretty well—compared to New York (and forget about Copenhagen) London does not, in my experience, offer many safe and protected lanes for cyclists.

The London congestion scheme does appear to have been very successful in one respect: significantly more people have started using public transportation and other means of getting around. So, even if the traffic has crept back up, imagine how much worse it would be if those folks now on buses and trains were clogging up the streets in cars.

In April, New York voted to begin congestion pricing south of Central Park with a program modeled on London’s. Why doesn’t New York emulate the more successful programs in Singapore and Stockholm? I suspect political will is an issue.

Transportation alternatives

Along with all these initiatives to deprioritize cars, there need to be other ways available for folks to get around. Otherwise, the system simply punishes those with less money. Without other good transportation options, the rich can afford to pay the extra costs while the poor can’t afford to commute. Public transportation and bike lanes need to be in place. Lots of cities, especially in the U.S., have poor public transportation due to the fact that they grew and expanded in ways that prioritized cars. They now have their work cut out for them, but at least they’re learning that the solution isn’t more freeways.

So, good news: these systems can work. They’re good for public health and safety, and they improve general urban efficiency. But there need to be transportation alternatives and the system has to be flexible. If done right, we may someday be able to stop organizing our lives around traffic. The fact is, as more and more people move into cities, we don’t really have an alternative.

This story is part of a collection called Pay for What You Get: Stories about paying for the true costs of how we use cities. Read more here. And read this article’s companion story, Spain’s Happy Little Carless City.