Diminutive and extremely rare, you’d be lucky to ever catch sight of a black redstart, one of the U.K.’s rarest birds. And yet, in the very heart of Britain’s sprawling capital city, sightings are on the up.

“To hear and then see a black redstart singing in the heart of London, it always gives me a buzz,” says Dusty Gedge, an ornithologist who’s spent his life recording the species’ metropolitan comeback. “So far this year, I’ve spotted six.”

The little bird’s resurgence reflects a sweeping change underway in London, where developers are embracing the concept of “rewilding” — returning indigenous flora and fauna to urban cores. Biologists say such efforts are critical to maintaining these areas’ biodiversity as cities grow and suburbs sprawl into natural habitats. Rewilding brings those habitats back, integrating them into cities so that animals and humans can coexist.

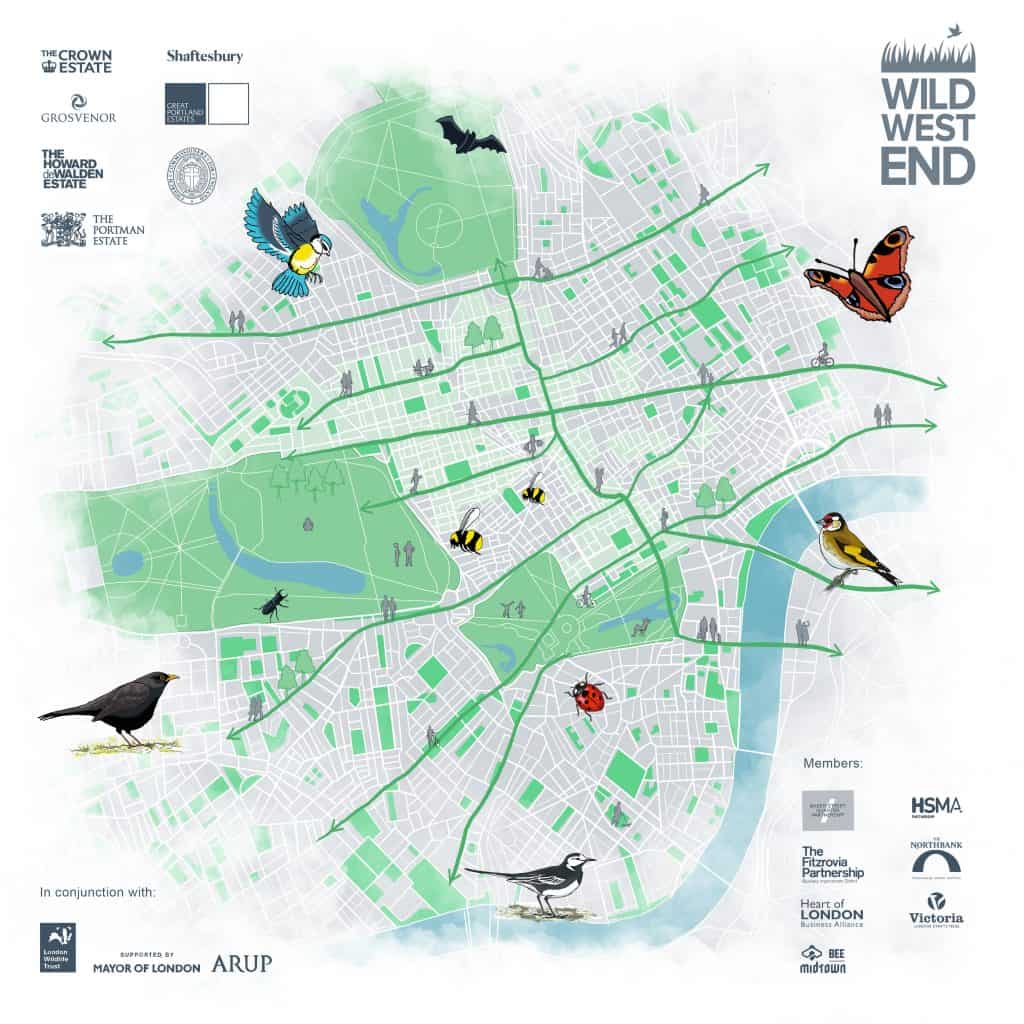

London’s Wild West End project is a prime example. Launched in 2015, the scheme set out to turn the city’s fragmented natural landscape into a place where native species could thrive, weaving pockets of greenery across rooftops, at street level and along the sides of buildings. The goal was simple: to create pathways of natural habitat along which wildlife can travel and flourish unfettered by human activity.

With seven of London’s largest property developers on board, progress has been swift — today, more than 2,500 square meters of green space stretch across the cityscape, encompassing dozens of green roofs, flower walls, foliage patches, planters, beehives and boxes inhabited by bats, birds and butterflies.

For Emily Woodason, senior landscape architect at Arup, an urban design firm that helped bring London’s Wild West End to life, the scheme’s success is clear to see.

“We’ve witnessed a significant increase in wildlife in the city center,” she says. “We’ve had some fantastic sightings, including types of bats rarely seen in central London, woodpeckers, and, of course, the black redstart, which had been in decline. It’s really fantastic to see that coming back into the city.”

To keep abreast of the project’s progress, Woodason and her colleagues conduct green space audits every two years. On the most recent audit in 2018, four bat species were recorded, including one, the serotine, that hadn’t appeared in the prior surveys. Observers also recorded great spotted woodpeckers, great tits and blackbirds, in addition to four sightings of the black redstart, which wasn’t seen at all in 2016.

These sightings speak to habitat restoration’s healing effect on ecological systems. Scientists recently tested the “bioscores” (a measure of ecosystem complexity and resilience) of green spaces around the city of Aarhus, Demark, finding a “positive relationship between urban wildness and biodiversity.” In Washington, D.C., pipes and drainage ditches have been turned into streams, and the city is planting 11,000 trees per year to cover 40 percent of the city in tree canopy by 2032. The early results are encouraging: shad are rebounding in the Potomac River, and native eagles and ravens are nesting in the city in increasing numbers.

Such anecdotal progress validates studies that underscore the ecological merits of returning urban land to its original owners. “Rewilding will often enhance a variety of ecosystem services, including the supply of freshwater, reduction in soil erosion, flood prevention and the removal of air pollutants,” writes Richard T. Corlett, a scholar of worldwide rewilding schemes based in China.

A look at America’s monarch butterfly population shows this ecosystem strengthening in action. An important pollinator and bellwether of environmental health, the monarch has been in decline in recent years — a trend that could be reversed with the introduction of milkweed plants across urban centers in the Midwest, researchers say.

In London, the return of wild habitats is a boon to local residents, too. Soho Parish Primary School, which sits in the heart of London’s West End, was an early beneficiary of the scheme, receiving allotment planters, soft landscaping spaces, bee and bird boxes, and a wormery fed with kitchen waste. The effect on pupil welfare has been marked, the school says, with increased opportunities for youngsters to explore nature, keep fit and play outside.

Survey data from people visiting the Wild West End Garden, another of the project’s installations, paints a similar picture. Among those who spent time at the site, an oasis of greenery just off London’s bustling Oxford Street, two-thirds reported an increase in feelings of wellbeing, with 29 percent dwelling in the area for longer than usual.

The findings are consistent with urban rewilding schemes emerging elsewhere. Local authorities in Dublin have, for the past five years, been fostering the return of native wildflowers and invertebrates long since absent in the Irish capital. Though the public response wasn’t uniformly positive early on — a tradition of well manicured lawns had to be overcome, explains the city’s biodiversity officer Lorraine Bull — Dubliners are now all for the natural approach.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.“If I’m ever doing a talk on biodiversity, I always say: ‘Look, the fundamentals of biodiversity give us our clean air, our clean water, and our food’,” Bull says. “So it’s really, really important in an urban context, as well as a rural context, to preserve as much biodiversity as possible. Over the past few years, there’s been much more public buy-in for that.”

When the scientific health benefits of urban greenery are considered, it’s clear this heightened sense of appreciation is well founded. A recent piece of research from the University of Adelaide, for instance, concluded that children exposed to wild environments are at a smaller risk of non-communicable diseases in later life, and experience less stress and anxiety.

A related investigation by academics at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) reached similar conclusions. “Studies have highlighted how people can cope better with major life issues, reduce their mental fatigue as well as improve attention capacity simply by being able to look at trees and plants from the windows of their apartment buildings,” said RMIT researcher Cecily Maller, noting the “strong social and community ties” linked to the expansion of urban nature.

Wild greenery can also play an important role in sequestering atmospheric CO2 — an issue of particular concern in London, where air pollution cuts short the lives of over 9,000 residents every year — a toll far higher than the majority of European capitals.

That, among other reasons, is why Woodason and her colleagues won’t be dialing down their Wild West End ambitions anytime soon. And though challenges remain, particularly around a paucity of space and changing climate, she’s optimistic about the future. That’s good news not only for London’s little black redstart, but for his human neighbors, as well.