Paved paradise put up an interstate describes the fate of much of 20th century America. And in many cases, those freeways drove their way right through the hearts of America’s urban centers. Today cities are trying to heal those old wounds. While urban America may never be rid of urban highways all together, they are, at least, finding ways to do yoga on top of them.

In 1955, when United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower was planning the expansion of the country’s highway system, he sent a committee report to Congress emphasizing the importance of building more interstate highways. It was obvious in the report’s conclusion that one of the major purposes of the new interstate highway system was to get people out of the cities.

“We are indeed a nation on wheels and we cannot permit these wheels to slow down,” the report stated. “We have been able to disperse our factories, our stores, our people; in short, to create a revolution in living habits. Our cities have spread into suburbs, dependent on the automobile for their existence. The automobile has restored a way of life in which the individual may live in a friendly neighborhood.”

In other words, highways were going to be designed to get people in and out of the cities more quickly—to move the masses from their suburban bedrooms to their city jobs and back again—not to make transportation easier for those who lived in the city.

Now, more than 50 years later, dozens of American cities’ downtown and inner city neighborhoods are still suffering from the effects of that thinking. City cores were slashed apart and chopped up into pieces, not only pelting those neighborhoods with noise and pollution, but effectively cutting entire neighborhoods off from the riches of the rest of the city.

Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx said in 2016 that the urban highways of America exacerbated economic inequality by devastating African-American neighborhoods for the benefit of suburban drivers.

“We have entire areas in this country where the infrastructure that is supposed to connect people is constraining them,” Foxx said in a speech at the Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank. “Achieving a middle-class life [in these neighborhoods] is made harder because of past transportation decisions.” In other words: along with being stinky and loud, these so-called “city gashes” are also deeply unfair.

Fixing this problem is not easy. Highways are incredibly big, incredibly expensive and incredibly ingrained in American transportation patterns. It would be herculean, to say the least, to get rid of them outright. As one urban planner told me, “It’s easier to build a freeway in a city than it is to get rid of one.”

But several American cities are showing that there is another way around the problem. Instead of reclaiming the highways, they’re capping them—bandaging these urban wounds with new parks, new real estate and, most importantly, new connections. And it’s a trend that is quickly catching on.

Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park is the poster child of capped urban gashes. The Woodall Rodgers Freeway was built in the early 1960s as a short link (less than three miles) between two major freeways in downtown Dallas. But it cut off the downtown area from the older Uptown neighborhood. In 2002, the idea surfaced to cap the freeway and was led mostly by the local real estate community. To complete the cap, they needed $110 million. They got that through $20 million from the city, $20 million from state funding and $16.7 million in a federal stimulus grant. The other $54 million came from private donations.

The five-acre capped park was completed in 2012. Today the lush, tree-filled park is home to music, food and movie festivals, dance nights, kids playgrounds, chess, croquet, yoga and fitness classes, and a lot of just plain chilling out. It has led to a 61 percent increase in streetcar ridership, it captures 18,500 pounds of carbon dioxide annually by way of planted trees and it reduces stormwater drainage by 64,214 gallons. A 1.2 acre addition to the park, which will cap another part of the freeway, is being planned now and is set to be completed by 2022.

“This freeway was like a toxic gash that cut through downtown,” said Jody Grant, a retired banker and chair of the foundation that operates and manages the park. “I think we made this a model for how public/private partnerships work. It was a time when we saw that downtown was stagnant, and this freeway was blocking use by everyone in the city. In the end, in order to give people a reason to come back to the city, you have to give them something to come back to. You can’t just build statues.”

In St. Paul, Minnesota, the state and city are considering expressway lids as part of a planning project for overhauling I-94, one of the main arteries through the central city. One of the decks would reconnect Rondo, an African-American neighborhood in St. Paul that was split in two by the highway when it was constructed in the 1950s. About 900 homes and businesses in the Rondo neighborhood were demolished by that highway construction, and it has suffered from a variety of urban cultural, economic, crime and health issues ever since.

“This [freeway] has been for more than 50 years now and it’s a nightmare,” said Marvin Anderson, former chairman of the board of ReConnectRondo said in a recent interview. “Can a land bridge bring that back? The land bridge is an idea, it’s a concept, it shows what’s possible when a community can come together.”

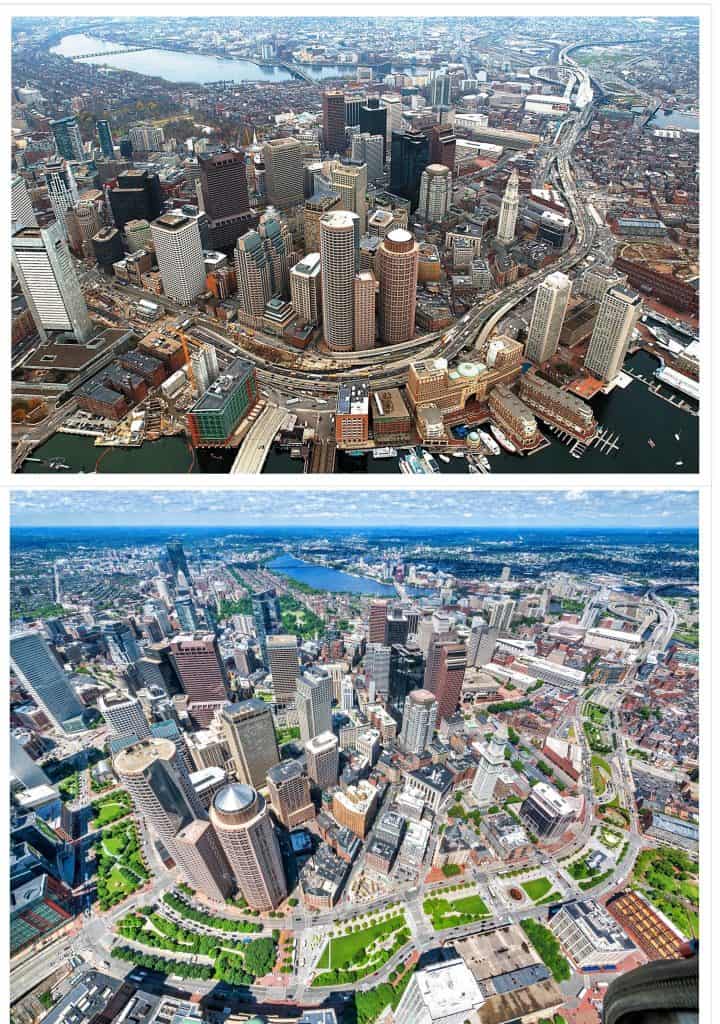

Alongside St. Paul are more than 50 cities considering capping their inner-city freeways. All of them are unique in scope and context, so it is nearly impossible to come up with a firm number that defines how much one will cost, how long it might take, or what the economic benefits might be. Chicago’s Millennium Park, built over railroad tracks, cost $490 million and opened in 2004, four years after the millennium it was intended to celebrate. The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway, created during Boston’s “Big Dig” to bury its Central Artery, cost $40 million. Almost half of the $110 million cost of building Klyde Warren Park in Dallas came from corporate and private donors, but that is not a guarantee in every city.

Clement Lau, facilities planner with the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation wrote in a recent study that “Capped parks offer hope and benefits that simply cannot be ignored. In particular, larger cap parks have the potential to: improve regional air quality; help reduce obesity and its associated problems; create short- and long-term jobs; raise adjacent property values; and enhance the overall quality of life.”

“While they can be costly and complex projects that are challenging to implement, cap parks represent a strategy that must be seriously considered to promote sustainability, address the need for more parkland and reconnect neighborhoods that have been fragmented as a result of freeway construction.”

That’s why cities like Boston (Rose F. Kennedy Greenway); Denver (I-70 through the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood); East Los Angeles (CA 60 through Belvedere Park); Pittsburgh (Cap Park over I-579 at the Hill District); Seattle (Freeway Park over I-5); Philadelphia (Penn’s Landing over I-95) and St. Louis (I-44 along the riverfront), just to name a few, are all finding ways to take the plunge.

Sometimes even more difficult to figure out than how to create this new land, however, is what to do with it.

Interstate 5 runs through downtown Seattle and the city and activists want to cap about eight city blocks of it to create an estimated 15 acres of new land. Seattle’s center city needs an estimated 28,000 more homes and 55,000 new jobs over the next two decades. Given that growth, and the need for more public infrastructure such as parks and open space, affordable housing, and other civic facilities such as schools or community centers, the capped acres on what is called “Lid5” might help solve those needs. However, there is talk that some of the open space might be best used by a big, local corporate entity like Amazon. That is a deal-killer for some.

“No one is saying let’s keep it the way it is because we love noise and pollution,” says John Feit, a Seattle architect and co-chair of a group studying the freeway capping issue. “No one is against it in principal. But we have what we refer to as ‘analysis paralysis.’”

Many see freeway capping as pulling together two purposes: increasing property values in urban downtown areas and making central city neighborhoods more functional.

Atlanta is studying the feasibility of the “Stitch,” a $300 million proposed project to cover portions of the I-75/I-85 freeway “connector” that creates a 14-lane gash through Atlanta’s downtown. It would include parks, a rebuilt transit station and land for new development.

But others say that the development must also work hand in hand with reconnecting neighborhoods bisected by 20th century urban freeway construction.

Initial plans for the Rondo project in St. Paul have that at the forefront: “Improvements are needed to not only repair the highway and restore mobility, but to also restore the sense of community and belonging once enjoyed in the corridor,” officials noted.

Recent three-term St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman (2006-2018) put it more succinctly: “It’s a first step. This is about rebuilding a community, not just making I-94 pretty.”