It sometimes seems we are constantly on the hunt for the best of all worlds when it comes to the climate, the environment and the economy.

So trust the Scandinavians to have hit the win-win-win jackpot. Though small in scale, new projects in Finland and Sweden are proving that energy production, environmental protection and, well, profit, don’t always need to be in conflict—in fact, they can go hand in hand.

The innovation revolves around a substance with a lot of buzz around it as of late, but one whose potentials are often deeply undervalued: biochar. So before we dive into Stockholm, first, a quick beginner’s lesson:

There’s something bizarrely perfect about the potential of the biochar process. A technique that transforms plant waste into a form of charcoal, biochar production both creates a long-lasting carbon sink and acts as an environmentally sustainable soil additive that greatly increases the productivity of agricultural land. Hence the buzz around biochar thus far. These qualities alone have been enough to create a global boom in its production, with the global market size reaching $1.3 billion in 2018.

This is good news in and of itself, especially because biochar is typically made from materials that are often considered garbage. While biochar can be produced from pretty much any plant matter, the typical source for Nordic-produced biochar is either plant waste or what the timber industry refers to as “thinnings”—smaller, juvenile trees cleared out from commercial forests to allow more space and light for larger trees nearby to grow to maturity. These thinnings were long considered such a useless headache that the Finnish government used to offer subsidies for their removal.

As recent developments have shown, however, there’s a lot more that the process can deliver.

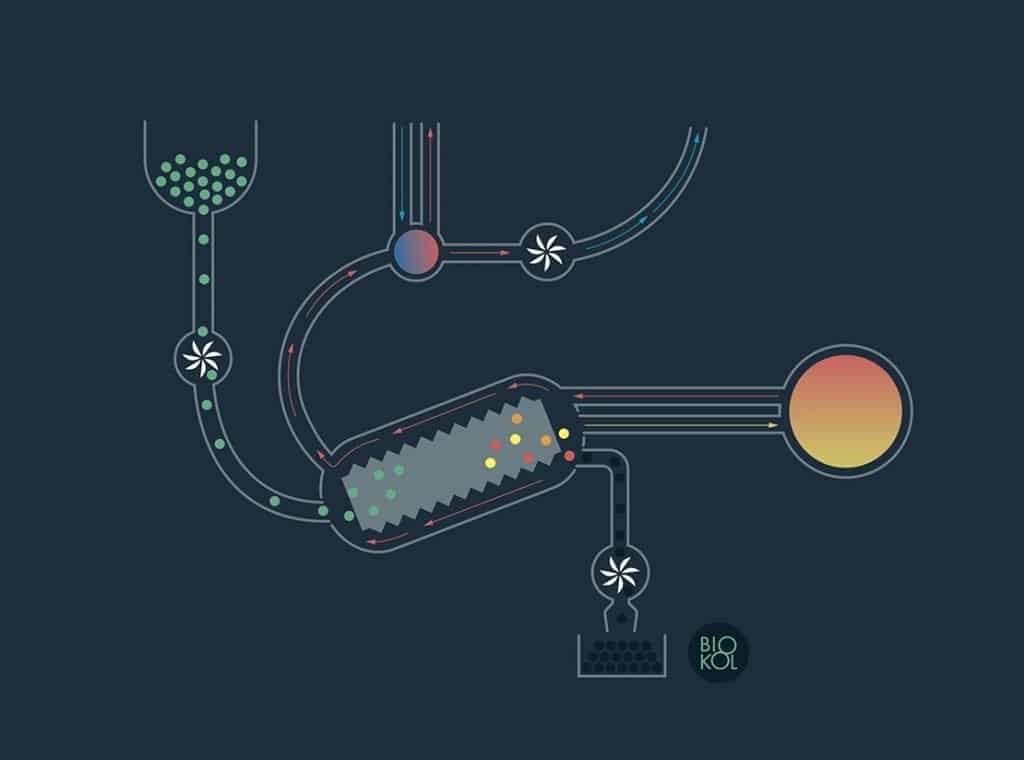

In Sweden and Finland, biochar producers are not just creating charcoal products, but also exporting the heat produced by the process to feed local district heating systems. By siphoning the heat from this process, local energy producers are able to create a remarkable virtuous circle with a new source of energy to warm local homes.

Sure, plant and wood waste products have been used to create heat before, by simply being burned. This in itself is no bad thing. The process is carbon neutral, because the burning only releases CO2 the trees have absorbed while alive. But turning the thinnings into biochar is far more environmentally beneficial. By heating the wood at up to 250 degrees Celsius in an oxygen-free environment, it is transformed into char that can remain un-biodegraded for thousands of years. As Sampo Tukiainen, CEO of Finnish biochar producer Carbofex explains:

“During this process, 55 percent of the carbon in the wood becomes char, while a further 20 percent becomes a pyrolisis oil that can be used as a blending stock for asphalt. Road applications of this oil are actually a long-term carbon sink too, because asphalt is recyclable.”

According to Tukiainen, converting wood to char releases 40 percent of the wood’s latent energy—less than the 80 percent released by straightforward wood burning, but still a substantial amount, and with significantly less carbon output. This heat is then channelled from the facility to a nearby combined heat and power plant that supplies a district heating system for homes on a neighborhood level.

The City of Stockholm’s municipal waste and water department is currently showing the way globally when it comes to extracting biochar’s full potential. Stockholm currently has five biochar production facilities working exclusively with green waste gathered within the city. Last year, they predicted that by 2020 it will produce at least 8,000 tons of char per year. That production output will be enough heat to warm 500 homes year round, which may not sound like much until you consider that in doing so they will have also sequestered the amount of carbon equivalent to removing 4,200 cars from the road.

And they’re scaling up. Jonas Dahllöf, planning and development director at Stockholm Water and Waste, explained that the city is currently considering handing the biochar project from the waste department to the energy department, who could easily increase that output by more than three times. “Exactly which approach we take is not yet fixed, but the city of Stockholm is totally behind the idea and want it to be scaled up as much as possible.”

Meanwhile, a new facility announced in July 2019 by the company Carbofex in Tampere, Finland, is already due to fully integrate biochar production into a new combined heat and power plant on a grand scale. Producing 30,000 tons of biochar per year, the plant will be able to generate 30 MW per hour of peak heat for local district heating systems, which it will do primarily during periods when natural conditions make yields from wind power and other renewable sources low. At this level, the plant could already generate enough heat to warm 10,000 single family homes, or 1,000 apartment buildings. The plant has the potential to scale up to four times that level.

And remember: this heat is all just a byproduct of something that sequesters carbon and enhances soil, which is its primary reason for being produced. Those properties are arguably still the process’s star attraction, as char greatly improves the fertility of soil by locking in nutrients. According to a recently published environmental research letter from the Institute of Physics, enriching soil with biochar could increase U.S. crop yields by between 4.7 and 6.4 percent, with improvement more marked when applied to less productive soils. That fertility boost has the potential to increase the annual U.S. domestic corn crop by between seven and eight million tons (if applied to all U.S. cornfields), while avoiding the potentially polluting effects of other commercial fertilizers and also leaving the soil in a better state. Currently U.S. agricultural producers constitute the world’s largest market for the substance.

Here, too, Scandinavia can still provide another lesson. Adding biochar to soil doesn’t just help agricultural production, it can also radically improve the health of urban plants and trees. Indeed, it is this specific quality that led to Stockholm’s own particular interest in the process.

In the early 2000s, officials in the Swedish capital noticed something interesting: while many trees seemed to struggle in urban conditions, one place where they were particularly thriving was alongside railway lines. Municipal tree expert Björn Embrén realized that this was because of something quite unexpected. The constant vibration from Stockholm’s traffic and construction work was causing soil to pack together, making it harder for water and oxygen to reach tree roots. Trees thrived next to railways, however, because the soil they were planted in was gravelly and loose.

The city realized it could replicate these conditions by digging biochar into the soil around trees. It even had a local source of fuel to create its own char-making process: green waste collected from the city’s own parks and gardens. They thus set up a remarkable system where green waste is being turned into char and producing heat before being plowed back into the soil where the waste had grown in the first place.

And on top of that, it’s lucrative. The city of Stockholm now sells back its biochar to local boroughs responsible for maintaining parkland. The business seems to work for both sides. Initially, the city estimated that, even giving away a quarter of its char free, it would recoup its investment within eight years and then go on to make an annual €854,000 (USD $945,700) in revenue. That estimate, however, has turned out to be too conservative, says Dahllöf.

“When we started we based out projections on a low price of €400 (USD $445) per ton, because we weren’t yet sure how high our char quality would be. Now, though, we have tested the char and it is really, really good quality—and we could easily sell it at twice the price without anyone raising an eyebrow. We realize too that we could potentially get more from selling climate-positive heat from this process.”

Perhaps the best news of all for those who worry about seemingly utopian Scandinavian miracles is that this is not just a northern European success story. Stockholm’s model has sparked interest from across the world, and it may even soon arrive in America. In July 2019, the city of Minneapolis announced that, inspired by Stockholm, it is studying the possibility of building its own biochar plant and extending the city’s environmental applications of char, a product Minneapolis has been using for some years.

It’s too early to say now, but there’s a possibility that, rather than being groundbreaking, combined biochar production and energy generation could one day be the new normal.