It was early 2018 when Matthieu Préel complained to his friend Michaël Roes about how costly and complicated it was to get rid of all the urine received by his waste management company in Bordeaux, France.

Surely there was some way to make use of this abundant liquid, Préel said to Roes, because paying to chemically dispose of the urine was beginning, frankly, to take the piss.

“Matthieu wanted to know if there was some way it could be reused,” says Roes, who at the time was working for a French biostimulant company, using natural plant processes to make crop yields more efficient. “I immediately thought it would be much easier to reuse this urine in agriculture.”

The pair conspired to no longer let this liquid gold go down the drain, and Roes soon began testing ways to see if the urine — which contains several important nutrients for crop growth including nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus — could be turned into an efficient, natural fertilizer.

The challenge was making it potent enough to compete with the leading brands, given that studies have found urine contains only one fifth of the nitrogen found in standard fertilizers and less than five percent of the potassium and phosphorus. That meant, according to Roes, every hectare of crop required around 200 kilograms of nitrogen — the equivalent of 30,000 liters of untreated urine. “But logistically, that’s too much for a farmer to deal with, and economically it doesn’t make sense,” he says.

At first, Roes tested concentrating the urine and then extracting the nitrogen. But the end product was more expensive than farmers would usually pay. So he tried something else: fermenting it and adding natural bacteria to help crops assimilate nitrogen from the air and the plants to absorb nutrients and water.

“When I did the tests, I saw it worked,” explains Roes, who went on to co-found TOOPI Organics, a French biotech company that collects and transforms human urine into fertilizer products, in 2019.

Testing carried out at Bordeaux’s National School of Agricultural Engineering found that the fertilizer later produced by TOOPI helped corn plants grow 60 to 110 percent more than a traditional mineral fertilizer.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

TOOPI has since set up its own factory close to the city of Bordeaux that is capable of producing 2,500 liters of organic fertilizer per day, with the aim of producing fertilizers that are less expensive yet just as effective as their industrial counterparts. Its process costs around two euros per liter — a fraction of the cost of competitors such as BASF, whose products cost around 40 euros per liter. By 2025, TOOPI aims to have 10 pilot plants worldwide.

But for all TOOPI’s talk of a “peevolution,” the idea isn’t entirely new. Less than a century ago, before the arrival of the petrochemical industry, half of all urine was still being recycled in Paris, according to Fabien Esculier, a researcher at the Ecole des Ponts ParisTech engineering school and lead of the OCAPI program, which is studying ways of reusing human waste.

The problem, Esculier says, is that now human urine is processed by a hugely flawed infrastructure network. In the European Union, almost 6,000 billion liters of drinking water is used to flush away urine each year, according to TOOPI’s estimates. Needless energy use, sewage pollution and antimicrobial resistance created by treatment facilities add to Esculier’s concerns. “We’ve developed our Western society since pre-war in a way that makes it difficult to exit this infrastructure,” he explains.

Yet already TOOPI has secured six million liters of urine per year from various stakeholders, and in April it was awarded 3.8 million euros in funding from the French government’s Agency for Ecological Transition to create a urine recycling network, improving the current infrastructure in conjunction with toilet manufacturers, designers, construction companies and waste collectors. It will source its urine from waterless toilets to be installed at schools, stadiums and businesses as well as gas stations, festivals and medical analysis laboratories across the country. TOOPI has also been selected to install waterless toilets at the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris.

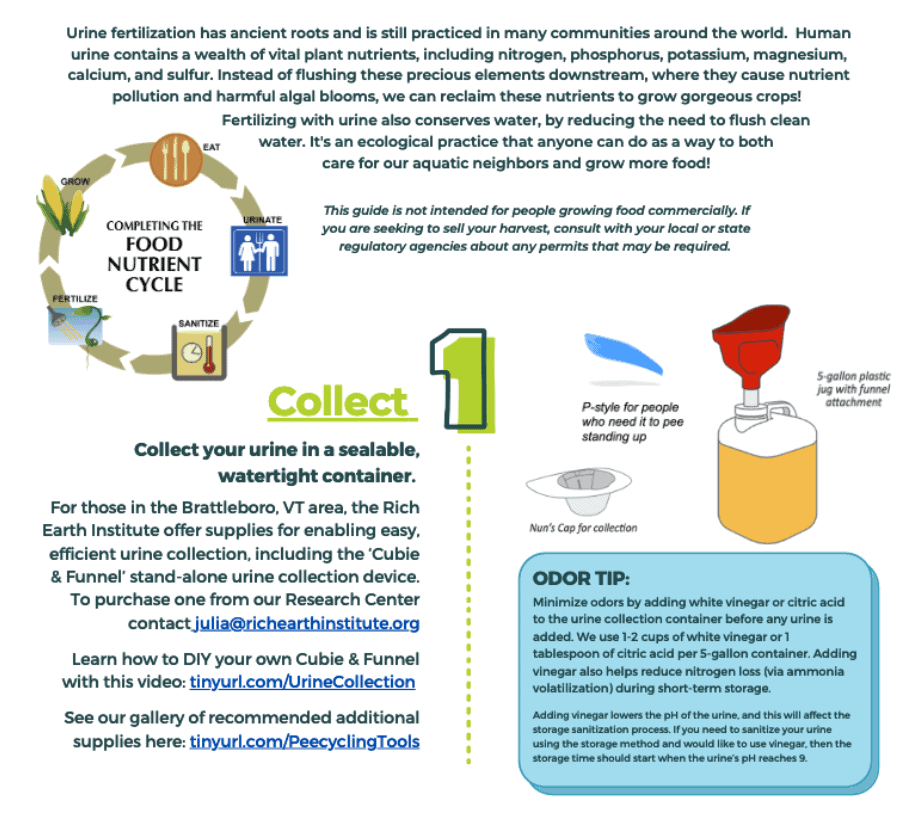

In the words of Kim Nace, co-founder of the Rich Earth Institute, a U.S.-based nonprofit that researches using human waste as a resource, if those infrastructure issues can be addressed this so-called “urine nutrient recovery” could prove revolutionary. Each human produces more than 450 liters of urine a year, she explains, and if harnessed properly it could benefit rather than cost society.

“We grow food, transport food and excrete it and it goes through centralized treatment plants,” she says. “The energy use is unsustainable and unfortunate. We need to manage our human waste in a different way — it’s a resource, not waste.”

The institute, which in 2014 was awarded the first permit to pasteurize urine in the U.S., is taking a localized approach to repurposing urine through initiatives such as “Urine My Garden,” which promotes the use of urine as fertilizer in private gardens, as well as projects with subsistence farmers in Mozambique and Kenya.

But for more significant changes in society to come about, Nace believes it’s only a matter of time. “The technologies need to mature, but they are developing fast,” she says. “It’s about the transformation of cities into more resilient, circular economies. Our imagination is the only thing holding us back.”