Ana Carlos likes to ride her horse down the semi-rural streets of Bloomington, California, where she bought a beautiful home on two acres for her family. “Everybody has fruit trees here, everybody has horses and goats,” she says. But five years ago, the school teacher and mother of three got a letter asking if she and her husband were willing to sell their home.

When she looked into the reason for the offer, she discovered that a developer had big plans. “They want to put over one million square feet of industrial zoning right in the middle of our community, bordering on three schools. The new warehouses will bring more than 7,000 daily vehicle trips to our town, including Diesel trucks.” Shortly thereafter, she found out that her small Inland Empire town was in the top one percent of a list no community wants to be on top of: Bloomington scores 99 on the CalEnviroScreen (CES), meaning the air pollution is worse than in 99 percent of the state. “We simply cannot take any more,” Carlos says. “If their plan goes through, it ends our community. I will no longer be able to play with my kids outside if the air gets even worse. Our lifestyle is over.”

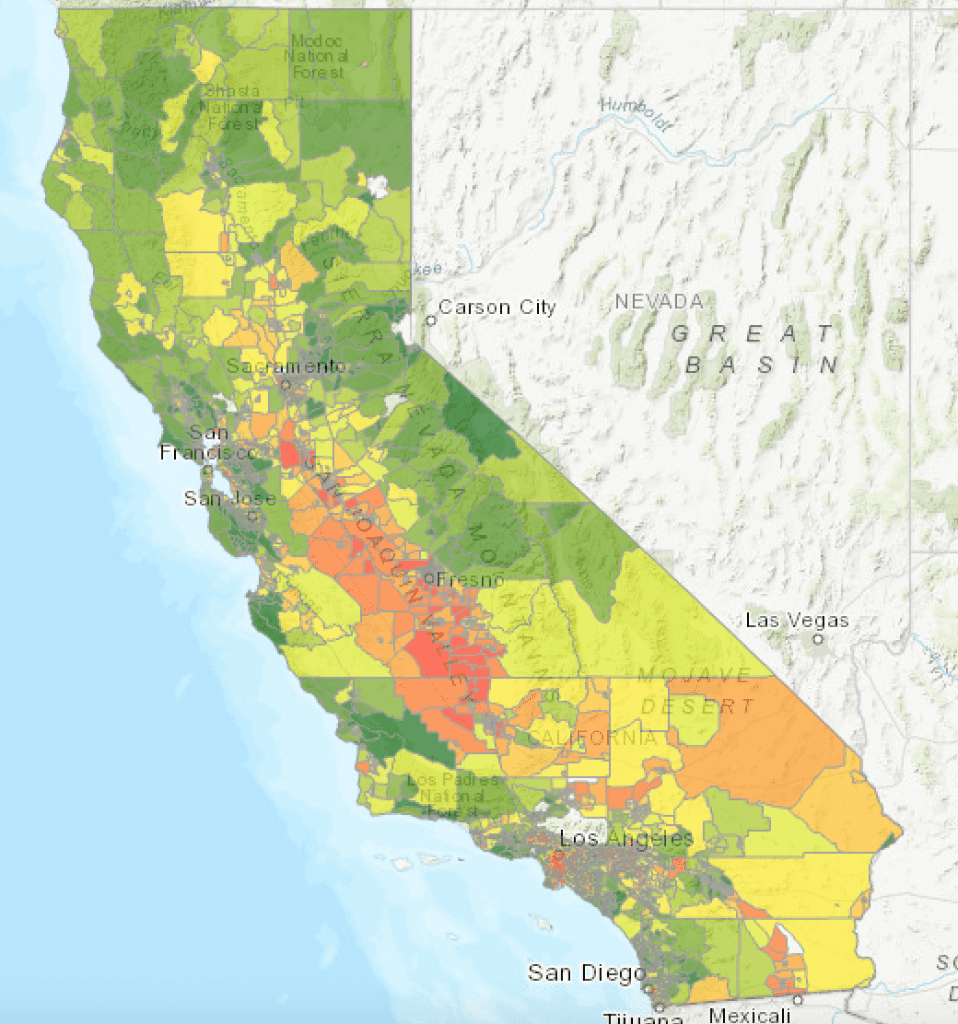

John Faust, who built the CalEnviroScreen, has a unique perspective on California. On his computer, he pulls up a map of the state. On the left and right, along the Pacific Ocean and mountains, are various shades of green. Between these is a cluster of orange and red patches: the state’s industrial and agricultural areas, with their dusty sunbaked plains, warehouses and refineries.

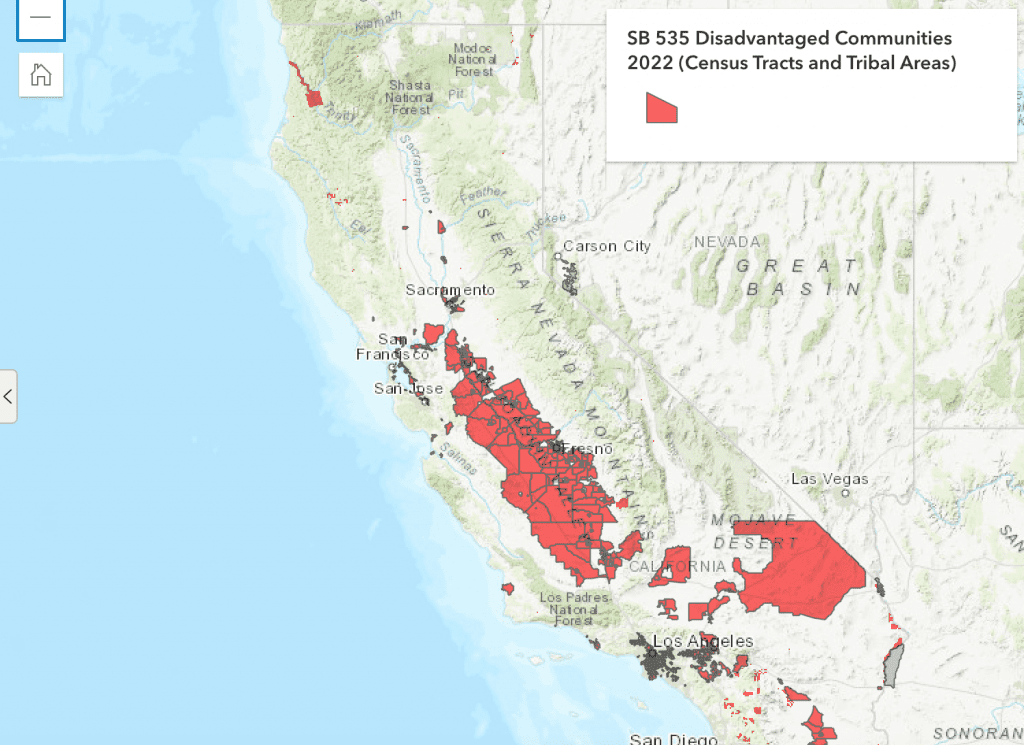

A toxicologist by training, Faust helped develop the CalEnviroScreen over the last two decades and now manages it for the California Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). He is also chief of the Community and Environmental Epidemiology Research branch of the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA). But these bureaucratic titles threaten to obscure the groundbreaking impact of his research: The 25 percent of census tracts with the worst CES scores must receive at least 35 percent of the investments funded by California’s cap-and-trade program. This enormous pot of money – some $20 billion – comes from polluters who must reduce or offset their emissions by paying into the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. It is used to finance a wide array of environmentally beneficial investments for the most polluted communities across California — everything from agricultural worker van pools to electric school buses to community air grants. In addition, CES data is increasingly being used in lawsuits — some of them propelled by the state’s attorney general — to block projects that would add even more pollution to communities already burdened with it.

The pragmatic use of this tool becomes apparent when Faust zooms in on one of the darkest red spots, an area southwest of Fresno. “98 ozone, 88 particulate matters,” he reads, which means that this district has more ozone and particulates in the air than 98 and 88 percent of the state, respectively. This finding correlates with the health and socioeconomic data the screen also displays: “Asthma 88, unemployment 98, and nearly 70 percent of the residents are Hispanic,” Faust reads. This, too, corresponds to the results in most of the state: The worse the air quality, the higher the rates of asthma, heart-related emergencies and underweight babies — and more often than not, the most polluted areas affect Black and brown people disproportionately. As Ana Carlos says, “What makes it really unfair is that these developers just see the cheap land and think it will be easy for them because we are primarily a community of color.”

The CES, which launched in 2013, is being used as a powerful corrective to such historic injustices. “As the state of California was developing its cap-and-trade program and polluters are paying into a fund as they’re emitting carbon emissions, we wanted to make sure that we can prioritize communities that are most heavily impacted by those polluting facilities,” says Sona Mohnot, the Climate Equity Associate Director at the Greenlining Institute, an economic justice public policy organization based in Oakland. “We know that environmental pollution is one of the many injustices that resulted from not just redlining, but a lot of other discriminatory land use policies and discriminatory environmental policies.”

Take the San Joaquin Valley, which has the worst air quality in all of the U.S. When the district issued yet another free pass in 2019 to exempt its four petroleum refineries from complying with state air quality requirements, a broad coalition of community members and activists sued. They found a powerful ally: California Attorney General Rob Bonta joined the lawsuit and they won, in part by leveraging CES data, which factors in not only the individual impact of each refinery, but the cumulative impact of all the polluters in the region. As a result, the refineries now have to comply with the state air quality regulations.

“This is a low-income, Hispanic community where a lot of the people are foreign laborers who are not going to say anything,” resident Jose Mireles, who lives down the road from a Kern Oil & Refining Co. facility that processes 25,000 barrels of crude oil daily, told the Los Angeles Times. “Sometimes you are inside your house, the doors are closed, the windows are closed, and you can still smell it.”

The CES has been used successfully in several other cases, including to block a cement factory in Vallejo and to upgrade facilities in the highly disadvantaged community of Stockton. “These are really good examples of how we can use data to address the multiple injustices communities are facing,” says Mohnot. “We have to make sure that the state walks the walk. How can we put our money where our mouth is, and ensure that 100 percent of those funds actually go into the most historically disinvested communities?”

In other lawsuits, CES data has led to compromise, in which the development it challenged wasn’t halted outright, but instead had to be built more responsibly. One example can be found in Fontana (which borders Ana Carlos’s Bloomington neighborhood), where residents are conflicted about the approval of another 200,000 square feet mega-warehouse next to a high school. In April, the courts decided that the Fontana warehouse can be built, but the rulings mandated ecological features such as solar panels, zero-emission trucks and a large donation the city can use for mitigating measures such as air filters.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.While the CES has helped environmental advocates rack up victories, critics point out that legislation that directly forces polluters to curb emissions would be more effective, because lawsuits aren’t always successful. For instance, a lawsuit against the Federal Aviation Administration and developers relied on CES data as it challenged the expansion of a former Air Force Base in San Bernardino that Amazon plans to use as a 650,000-square-foot cargo hub. More than 500 additional trucks and two dozen cargo flights are projected to pollute the area daily once the hub is fully up and running. Already, thousands of trucks buzz through the neighborhood most days, often forming long queues in front of the warehouses, spewing Diesel fumes while waiting to unload their freight. Again partnering with lawyers from the Earthjustice Institute, Bonta’s office used the high asthma and bronchitis rates in the nearby communities as proof that the residents should not bear any more pollution, but his challenge was rejected.

The project sparked contentious debate. Ninety-five percent of the residents near the new Amazon hub live below the poverty line, and some argued they would rather breathe bad air than sacrifice the jobs. Mohnot believes this to be “a false choice. No one should have to pick between their safety and being able to provide for their families.” More than one billion square feet of warehouse space now covers the Inland Empire, much of it built on former farm and ranch land, and offering mostly low-paid temp jobs, according to the Robert Redford Conservancy. “None of my neighbors want these jobs; you can’t build a career on it,” Ana Carlos says. “We spoke to hundreds of community members and out of hundreds, only one said, maybe it’s good for the jobs.”

This speaks to the other aim of the CES, which activists are using as a tool not just to support lawsuits and force companies to reduce emissions, but to bring investment to communities overburdened by environmental hardship. Mohnot says her colleagues at the Greenlining Institute are working with entrepreneurs and startup companies to use the CES to pilot clean energy innovations in these communities and work with local manufacturers to increase economic opportunities there. “We want to work toward a policy solution where we can create an oil and gas transition fund, so that folks who are dismissed from those jobs are able to access funding and training opportunities into similar work but in renewable energy. We want fewer gas and oil industries but also make sure folks aren’t jobless at the end of the day.” However, this is not happening yet.

But the CES findings have already provided the basis for innovative strategies. For instance, the Greenlining Institute co-sponsored bill AB 2722 that created the Transformative Climate Communities (TCC) program, which relies on the CES to prioritize the most vulnerable communities. “If you’re a small or under-resourced community and you want environmental services, whether it’s recycling, urban tree canopy, access to better transportation, bike lanes, whatever, you may have to apply for six different grants to get those holistic benefits,” says Mohnot. “This can be very cost intensive and lead to fatigue, so we wanted to streamline that process. Now that community can apply for a slew of greenhouse gas reducing services through one grant program, and it’s meant to be at a neighborhood scale.”

Keeping CES data current is a challenge. “Some data is continuously updated, and some only available annually or every couple of years,” John Faust acknowledges. In other words, the CES won’t tell you the current air quality in your hometown this very minute. “We’re looking at big picture trends,” is how Faust puts it. Most of the effects of the pandemic and the recent wildfires haven’t been included in the latest version of the CES. Also, not all data is readily available. For instance, the CES factors in the agricultural use of pesticides but not the non-agricultural use because this information is hard to gather. Moreover, Mohnot believes that California needs a similar tool that measures climate risk, not just pollution and poverty.

California’s strategy of prioritizing communities hardest-hit by environmental injustices is now about to become national policy: Last week, the administration announced it is launching a new Office of Environmental Justice to address climate change and pollution in low-income and minority communities. The new office will identify places that “bear the brunt of the harm caused by environmental crime, pollution and climate change,” said Attorney General Merrick Garland, and focus enforcement efforts on mitigating those effects.

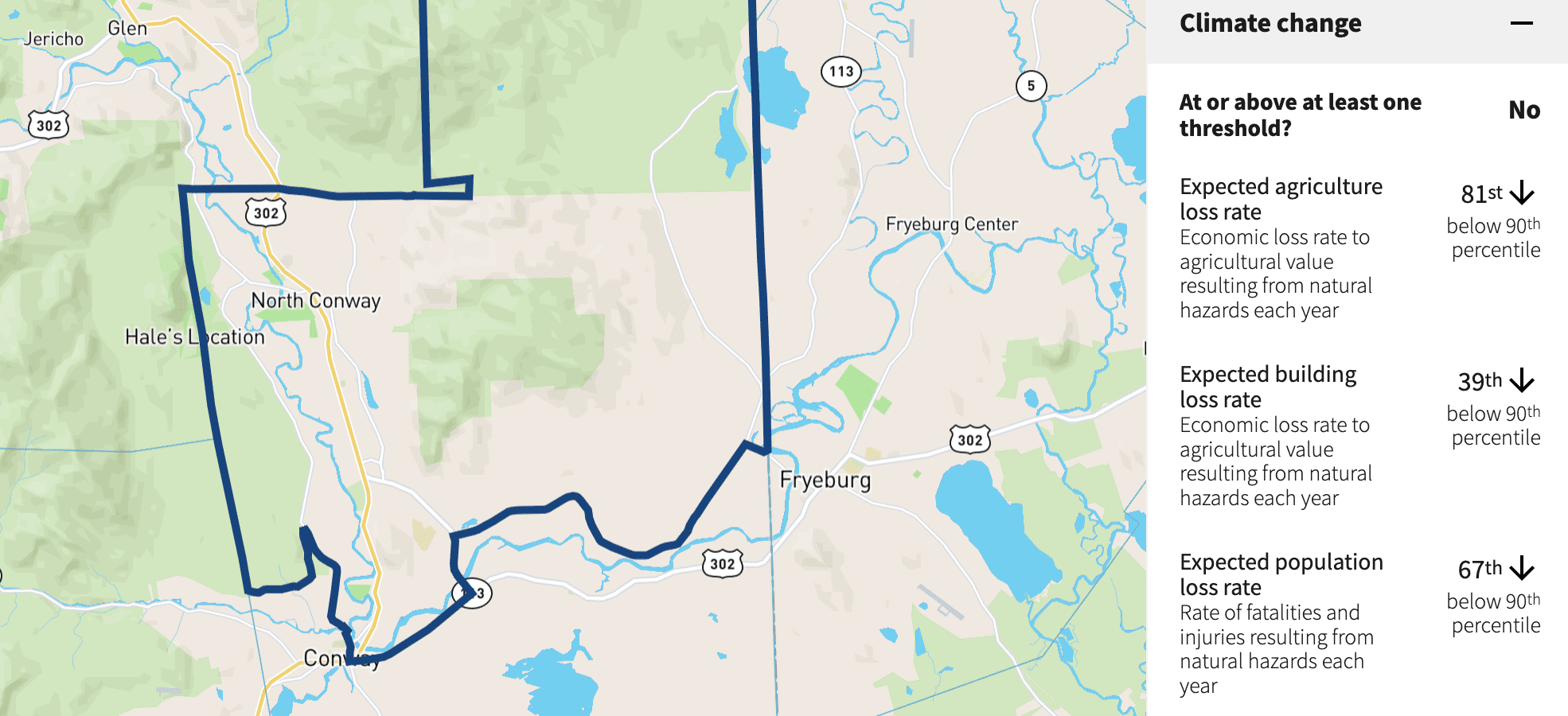

In addition, earlier this year, the federal EPA entered into a partnership with California to share tools and resources. Other states are taking note, as well. New York just launched an environmental justice unit that is looking into building a New York version of the CES. And in February of this year, the Biden Administration released a beta version of the “Justice 40” program, which stipulates that at least 40 percent of the benefits from the government’s investments in climate-related programs, including infrastructure and clean energy, will go to underserved communities. The administration modeled its tool for assessing these needs, the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST), on California’s CES.

Meanwhile, Ana Carlos hopes that the supervising board of her small town, Bloomington, “will vote in the interest of their constituents who voted them in — that they will make the decision that is best for our health, our families, our homes, our community.” But when she asked about the prospect, she was told that the board has never voted down a major business development.

However, this school teacher has learned that she is not alone. “We have learned how to organize a community. If the developers think they can just push us out of the way, they are wrong.”