This year, Scalawag challenged media outlets to embrace Abolition Week by focusing on alternatives to the deep injustices of the prison system — something we at RTBC report on a lot. This story features the work of one of several amazing organizations participating in Scalawag’s virtual event, happening tonight, Realizing Abolition.

—

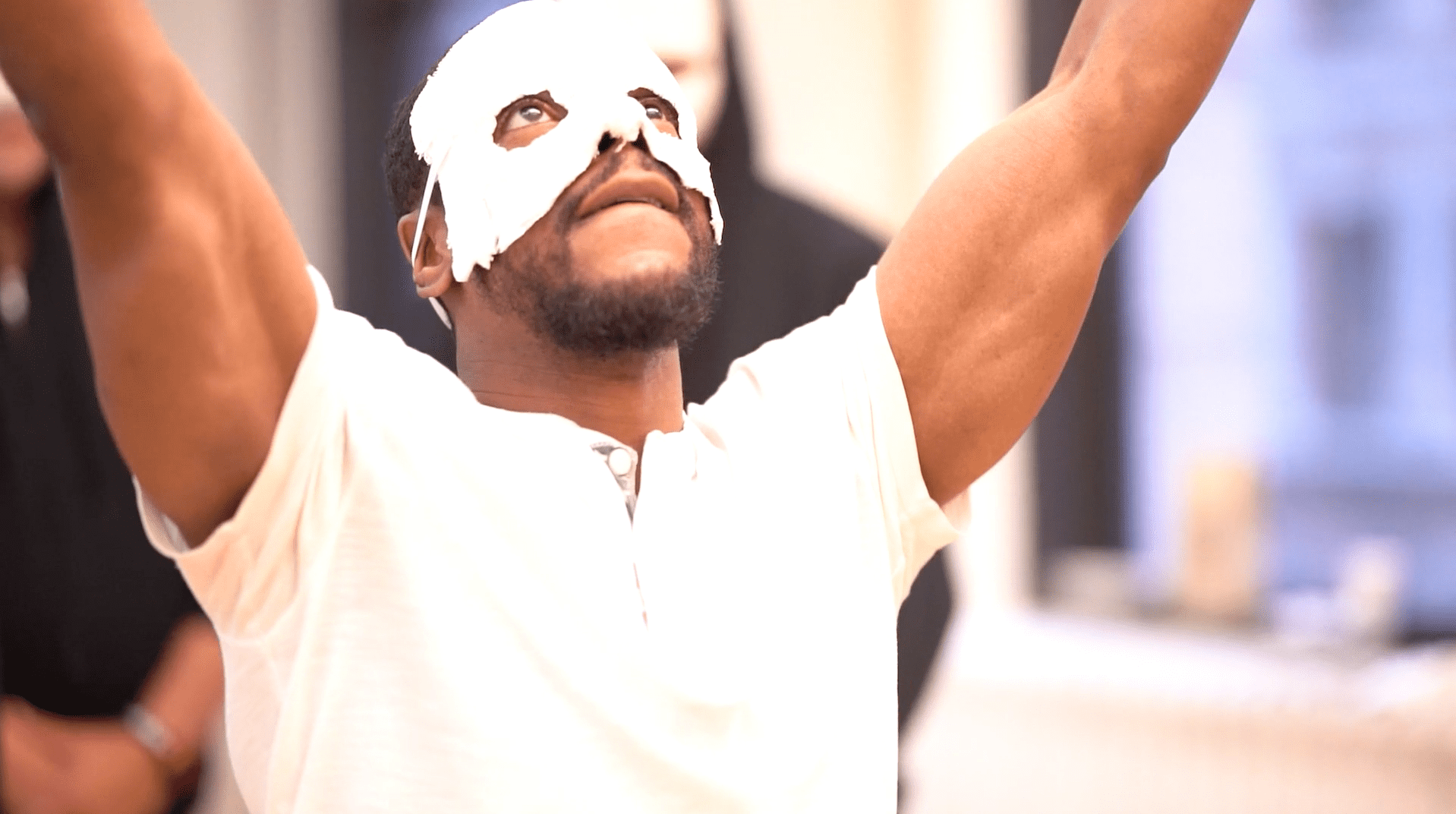

“Meet Bruce — The Mask” the video begins. Bruce introduces himself on the screen and explains that his mask serves as a representation of stigma. He proceeds to apply strips of paper mache onto his face as he talks about the stigma he’s faced through his life, before, during and after his incarceration. “Many times I’ve been called a criminal,” he says. “So I want to put on a few of those strips to represent those many times.”

He adds more and more white strips, covering the top of his face, then writes “Shame” in red letters across his forehead. “How does this look?” he asks his virtual audience. “Don’t look too good, huh? Would you like me to walk around in the street looking like this? You probably wouldn’t. So stop stigmatizing me.”

Bruce’s performance kicked off the first ever virtual rite of passage for Ritual4Return, a program that guides men and women through rites of passage to transition from incarceration back into the community.

The idea for Ritual4Return originated with community-based theater artist Kevin Bott, who studied a 50-year body of criminology and sociology literature on the potential of rites of passage and storytelling tools for people leaving prison. His resulting dissertation pulled from works like But They All Come Back by Jeremy Travis and Making Good by Shadd Maruna.

What he found was that rituals abound when it comes to bringing people into the criminal justice system. Yet, there aren’t formal rituals to welcome people back to society after they serve time.

“What drew me to the program was how Kevin described that during his research, he learned that the legal system is very much a ritual, but it’s a ritual that degrades people from citizen to all types of negative labels. Once you’re done, there is no community there to greet or embrace you, unlike all the rituals you know like baptisms and weddings,” says Lisette Bamenga, who participated in a rite of passage in 2019 and is now part of the leadership team. Woven into the mission statement of Ritual4Return is to transfer leadership to people impacted by the criminal justice system, who have experienced the rite of passage.

Bott led the program’s first rite of passage in 2008. Alex Anderson, a social worker, participated and stayed on in a leadership role. Anderson views the experience as a marker between two different lives: the first encompassed his incarceration and dealing with the shame of incarceration coming home. After his ritual, he was in a place of self forgiveness, self acceptance and self worth.

The process is “a demanding journey,” as the program literature states. “It pushes people intellectually, physically, emotionally, and spiritually as they define and then cross the thresholds that mark the transition from old patterns, behaviors, and identities into the new life they seek to manifest.”

The resulting performance to finalize the rite of passage is also demanding and emotional. For one women’s rite of passage, which took place in December 2019 at The National Black Theater in Harlem, each participant took the stage to share stories and performances about their incarceration, past hardships, resilience, dreams and goals.

After the performances, Bott and Anderson asked each woman to return to the stage, this time surrounded by friends and family. The group affirmed a declaration to “respect, trust, value and support you faithfully … regardless of the obstacles we may face together.” After these personal declarations, Bott asked the audience to gather in small groups to discuss other ways they could support the women crossing the threshold.

“It felt like getting my voice back — I wanted to be back where I was, before my incarceration, and continue moving forward,” says Bamenga of that process. She adds that the “sisterhood bond” formed within her cohort was another core component.

It took almost a decade for enough funding and support to come through to formalize the program after its initial trial run. In 2019, Bott and Anderson led two cohorts for men and women. Participants received meals, subway fare and $500 stipends to participate. Once a week for 12 weeks, they met inside a rehearsal room at the Stella Adler Studio of Acting on the southern tip of Manhattan (artist director Tom Oppenheim is a program supporter) to learn about performance, storytelling and creative expression. They had guidance from Bott, Anderson and visiting teaching artists, but most importantly they used the space to develop and refine their own rituals, which ranged from spoken word, poetry, dance and song.

Anderson believes in the rite of passage so much, he’s continued even as funding runs low. The stipend for the most recent women’s cohort, he notes, was paid by small individual donations, including money from past Ritual4Return participants.

Since 2009, 28 people have graduated from Ritual4Return. Though the number is modest, the impact on participants is clear. “No one can tell your story except for you and no one has gone through that type of suffering except for you. We can learn from each other’s pain, writing and any type of art,” says Sammie Werkheiser, a participant of the latest women’s cohort. For her rite of passage, she performed a spoken-word piece entitled Tiger Lily and Star Gazer.

“Reacclimating is difficult for anyone … going to prison is not a normal or regular thing, so it’s not like in my hometown there are many people I can talk to about it,” Werkheiser says. For her, the cohort provided a safe, supportive space among other impacted women. “For me, the performance was the least important part of it.”