This story uses SoundCite — click on words that appear grey to hear the music associated with them.

When A., a mother in Canada, needs to calm her two-year-old daughter, she sings the lullaby she wrote especially for her. For the length of that song, everything but mother and child fades away, and their love is the whole world.

There was a time when A. couldn’t hear the music.

“Me and my daughter moved into a transition home when I was pregnant because her father was threatening to cut the baby out of me,” says A., who left her abusive partner in 2017. “Because of how she was conceived, and also spending my pregnancy in a transition home with an uncertain future, my relationship with my unborn child was complicated… All of that trauma had a huge impact on my ability to bond with my baby.”

It’s one thing to become a mother; it’s another to feel like one. That feeling, the one A. experiences when she sings to her baby, is crucial to the health and well-being of both mother and child. It is the seed that Carnegie Hall’s Lullaby Project helps plant by helping mothers in difficult circumstances across the continent write lullabies for their babies.

Turning pain into a healing prayer

In the United States, A.’s circumstances are far too common. Save the Children’s 2015 State of the World’s Mothers Report ranked the United States 33rd in terms of mothers’ support and well-being, and the CDC reports that infants are more likely to die in their first year of life in the U.S. than in any other wealthy country.

Mothers living in poverty (which includes at least 63 percent of teen moms) face the longest odds. For example, Save the Children notes that infants in the poorest section of Washington D.C. die at a rate ten times higher than those in the richest section. These structural inequalities require large-scale solutions, but baby-sized ones can help, too.

The Lullaby Project originated in 2011 at Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx, where teaching artists from Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute were conducting songwriting workshops with HIV-positive teenagers. The workshops’ in-hospital concerts caught the attention of a nurse and psychologist from the OB-GYN department, who asked if they could do a similar workshop for the hospital’s teenage mothers. And so, the Lullaby Project was born.

“They said, ‘we have these pregnant teens, and the main problem for them is that they have difficulty attaching to their children, especially in the first year,’” recalls Tom Cabaniss, a Carnegie Hall teaching artist and Lullaby Project founder. “Because, first of all, they’re teenagers, and there’s some stigma that goes along with having a child at that young of an age. But then there’s also the fact that the families — in a good way, in a certain light — tend to take over… And so the mothers themselves, it’s almost like they sort of skip being a mother because of the position that they’re in.”

Though the program has gone through some modifications, and the number of songwriting sessions can vary, the essential process is always the same. Carnegie Hall teaching artists, from ukulele players to bassoonists, talk with the mothers about their dreams for their children.

Based on those conversations, the mothers write a poem or letter, which the musician converts into song lyrics. On the second day, mothers and artists write the music together, and the musicians arrange it and take down sheet music. The project culminates in an in-studio recording session with professional musicians performing the piece. The mothers are in the producer’s chair, and often, they choose to perform the vocal tracks themselves.

The programs take place in settings that challenge mothers the most: neonatal intensive care units, prisons, high schools, even a refugee shelter on the Mexican border.

At the end, each participant is given a copy of the recording, along with a framed copy of the lyrics.

“I started the Lullaby Project when my baby was just seven weeks old,” says A., whose lullaby “Child of a Star Breather” tells the story of a treacherous journey that leads to great love. “The process of trying to write a song for her was very healing. It was a chance to think about and work through the difficult emotions. I’m probably the only one with the word ‘demon’ in my lullaby! But through the process, I was able to take all the trauma and pain I had and… turn it into a beautiful healing prayer.” (Listen to “Child of a Star Breather” and other lullabies at the end of this article).

A report card

Teaching artist Emily Eagen, who has worked with the Lullaby Project since the pilot program (and throughout her own two pregnancies) describes an enormous mental and emotional shift that takes place for mothers during the songwriting process.

“Having a creative approach to what it means to be pregnant can really save you,” she says. “It keeps you from the panic of how it’s going to go, or all the logistics that are coming into your life… They come forward in everybody’s life, but particularly the women that we’re working with, who are usually in really challenging circumstances, where they feel the crunch of money and sometimes housing instability, or separation from family.”

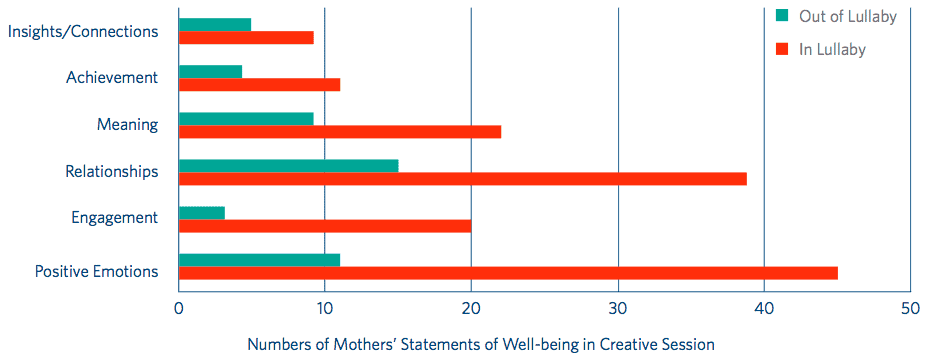

To evaluate the program’s impact, Carnegie Hall commissioned a study from the arts research firm WolfBrown. Their 2017 report suggests that the project encourages language development, expression of feelings and connection with family members, all of which have a positive effect on the growth of the infant and the health of the mother. During Lullaby Project sessions, women talk more about achievement, meaning, relationships, engagement and positive emotions than they do in their lives outside. WolfBrown’s research also includes some notable results that are difficult to quantify, like the transformation that occurs in the mothers when they transition from talking about their lives to writing the lullaby:

As they work on and talk about their lullaby, mothers have a moment to step back, discover insights and make connections between different parts of their lives. They share positive emotions and relationships, a new or re-discovered sense of personal meaning and achievement, new insights, and hopes for the future. These are all signs of well-being. By comparison, when mothers talk about their experience outside lullaby, they are much more matter-of-fact, less positive, and unsure of what they will be able to do as parents or as adults in the world.

Studies of similar programs around the world echo these results. A 2018 study reported in the British Journal of Psychiatry found that women who sang with their babies and created new songs reflecting on aspects of motherhood experienced “a significantly faster decrease in symptoms” of postpartum depression. Other studies have shown that singing and lullaby exercises can help reduce prenatal stress in mothers, aid weight gain in premature infants and decrease the amount of time that newborns spend crying.

The Lullaby Project gives the mothers opportunities to stay connected by offering invitations to free family events, and in some cases, a chance to intern with the program or even perform their songs at Carnegie Hall. The songs that are recorded or performed professionally are officially licensed so that the mothers receive a percentage of the profits, so long as their contact information is accessible to Carnegie Hall. The project takes this financial compensation seriously, too — Cabaniss mentions that the program has been unable to locate one of the songwriters, a former Rikers Island inmate, so their proceeds are being held in escrow.

Room to Grow

By the fall of 2012, after two successful sessions, Carnegie Hall was eager to grow the Lullaby Project. In 2013, they set up Lullaby projects at Siena House, a Catholic shelter for pregnant women, and at the jail on New York’s Rikers Island.

“Working in Rikers has another dimension to it, because parents are separated from their children and don’t know for how long,” says Eagen. “So Tom always says that those lullabies feel like they want to send a message. And they really create a thread between the parent and the child that can stay when they’re separated.”

As word spread about the Lullaby Project, Carnegie Hall began receiving inquiries from organizations around the country, eager to do the workshops themselves. While the Weill Institute couldn’t financially support every offshoot, they encouraged partnerships and began hosting conferences with interested parties. Further publicity came in 2018, when Decca Records released a compilation of lullabies. Titled Hopes & Dreams: The Lullaby Project, it features the songs of New York City mothers performed by artists like Fiona Apple, Patti LuPone, Angelique Kidjo and opera star Joyce DiDonato (who was influential in creating the album).

The Lullaby Project now reaches hundreds of families annually, with 10 sites across New York City and partnerships with more than 40 organizations nationwide and around the world, including the Vancouver offshoot in which A. participated, run through the Canadian nonprofit Instruments of Change.

The songs, more than 700 of which can be streamed on the Lullaby Project’s Soundcloud page, encompass many languages and even more musical styles, from Indigenous drumming to traditional folk waltzes and hip hop. “We can go in and right away, people are rhyming, you know, boy with joy or night with light,” says Eagen. “And within five minutes, each song will be a completely different song from all the other songs that have those same rhymes.”

For Eagen, the Lullaby Project is nurturing a vital and underappreciated type of songwriting. “We don’t have a global vocabulary of songs that describe motherhood,” she says. “We have lullabies that describe the baby, and we have love songs. But love songs from parent to child? Over the past seven years, it’s been a real interest of mine to help create more of them.”

Cabaniss and his colleagues are now trying to figure out how to extend the Lullaby Project into more of a long-term relationship with participants. One of their next initiatives will be early childhood labs, where lullaby authors and their children will participate in an immersive music class that uses their own songs. Other Lullaby Projects have taken their own steps to encourage long-term participation.

Cabaniss is particularly impressed with the Lullaby Project at the Hiland Mountain Correctional Center in Alaska, which works with incarcerated Inuit women and men. When participants are released, they are offered a paid job with the Lullaby Project, teaching songwriting to other mothers. As he puts it, “They found a way to take that whole self-esteem idea and kind of pump it with steroids.”

As far as Cabaniss is concerned, the potential for the Lullaby Project is limitless.

“In the first couple of years, we had a staff member who said, ‘Okay, now we’ve written 70 lullabies or something in this project. Are we done?’ Like, ‘How many lullabies can you write?’” Cabaniss recalls. “And the answer of course is, how many children are there?

Listen below to a few of the lullabies written and performed by Lullaby Project mothers, and read their stories.

—

“Child of a Star Breather” by A.

“‘Child of a Star Breather’ was my musical prayer for my daughter’s life. My daughter just turned two in July and I still sing the lullaby to her all the time. She ended up having colic, and there were months where she would just scream for hours and there was nothing I could do to console her. Having the lullaby and singing it every day allowed us to get through that period and the song became a sort of comfort blanket for her.

As she has gotten older, she is very hyperactive and challenging to parent at times, the lullaby remains a touchstone that helps me calm her down… I am so thankful that I got to take part in the project and so thankful that my daughter will have the gift of her song for the rest of her life to know how much I love her. And when she gets older and has questions about where she comes from or who her father is, I feel like the song will be a healing and gentle way to explain to her how she is the light that came from the darkness.”

“My Beautiful Young Man” by Janayha (live version above in video)

“I was attending the LYFE program at Bronx Regional High School [which provides free care and education for the children of students], and a social worker by the name of Jodi Kaltner, she called me into the office and asked me if I’d like to write a lullaby. She explained what it is, and I was like, okay sure.

Liam was only three when I wrote it, but he was already so strong, so independent, so kind and affectionate, so I kind of just wrote it all down. I’m really grateful for the experience, because it led me to have a job as an intern here [at Carnegie Hall]. When I help other moms write lullabies, I tell them not to think too hard, because it’s not as difficult as you think it would be.”

“Aaron’s Song” by Gemma

“‘Aaron’s Song’ means the world to me. We love music and I love this particular way to tell my son how I think, feel, believe, and breathe about him. It is my way [of making sure] that maybe when, in the future, I am not with him, he will have something to keep in mind and he can pass along to his children, in case that happens.

Sometimes, the events in our lives turns us upside down or knock us to the floor, but our love and mind can help us to move on. After I left my country to start a family in Canada, I never expected I would be facing lots of sadness and struggle to keep my son safe. And thanks to all the angels and good people in Canada, I could give to my son a lovely toddlerhood, and I am working day to day so that he will have a peaceful childhood, until he becomes a good man that I [hope] is happy and helping others around him. This song states that in every word.”