This story is part of The New Climate Economy, a series about how the Inflation Reduction Act is accelerating investments in climate action. It is produced in partnership with Nexus Media News.

Before he joined the Civilian Climate Corps, Robert Clark assumed building and electric work was all low-skilled labor, akin to “working at McDonald’s,” he said. That was before he learned to install electric heat pumps, maintain electric vehicle charging stations and perform 3D image modeling of spaces about to get energy upgrades.

The apprenticeship program has been life-changing, Clark said. Before joining, he struggled to find work, in part because of a felony conviction for burglary. “It’s a no-brainer,” he said of joining the Civilian Climate Corps, which pays him $20 per hour to learn skills and receive the certifications that he needs to get work. He hopes to go back to school to become an engineer.

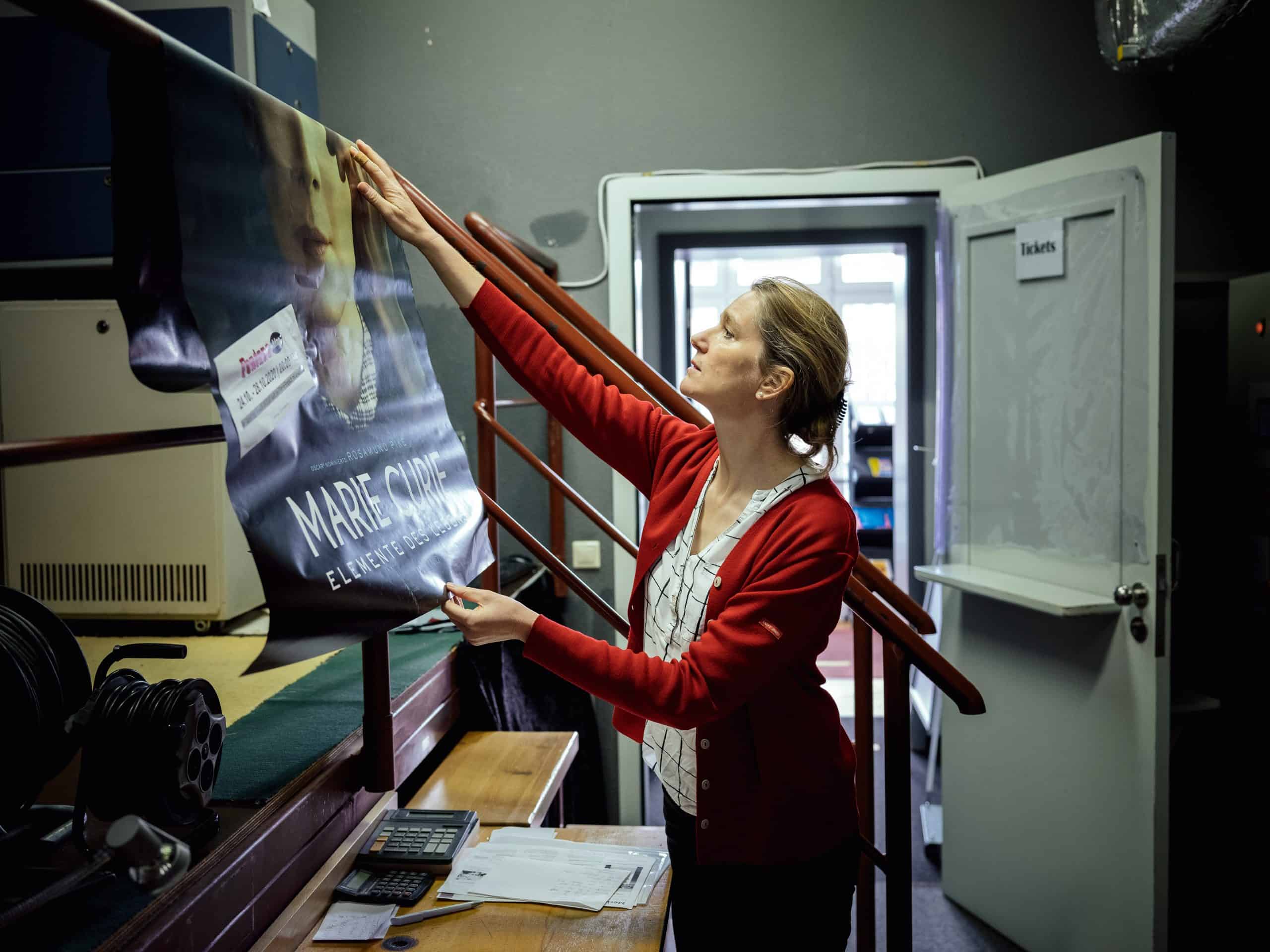

Clark is one of 1,700 New Yorkers who has gone through the Civilian Climate Corps, which was developed by BlocPower, a Brooklyn-based building electrification startup, and the city of New York.

The program, launched in 2021 with $37 million from the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, has a heady dual mandate: develop a workforce that can help the city meet its ambitious climate goals and bring those jobs to neighborhoods affected by gun violence.

“The labor supply is a big problem, but it’s also a massive opportunity,” said Donnel Baird, CEO and founder of BlocPower. Baird grew up in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, where he said many Black and low-income families like his own would turn on their gas stoves in the winter to make up for inefficient heating systems.

“We are going into the lowest-income communities, where folks are at risk of gun violence — personally, their families, their communities — we’re training them on the latest, greatest software to install green infrastructure in urban environments, in rural environments,” Baird said in 2021. “That’s going to solve not only crime rates in low-income communities in New York City,” he added. “It’s [also] going to solve the business problem of the shortage of skilled construction workers across America.”

In several studies, access to jobs has been shown to correlate with lower crime rates; one study of youth employment in New York City revealed a 10 percent drop in incarceration for those who had summer jobs.

New York has ambitious plans to decarbonize its buildings, the city’s largest source of emissions. It has banned gas connections in new buildings and put caps on how much existing buildings can emit. By 2027, all new buildings will need to be fully electric. Officials say those changes will help the city reduce building emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.

New federal tax credits that are part of the Inflation Reduction Act provide additional incentives for developers and homeowners to replace outdated gas furnaces and boilers for electric upgrades.

There’s just one problem: there aren’t enough skilled workers.

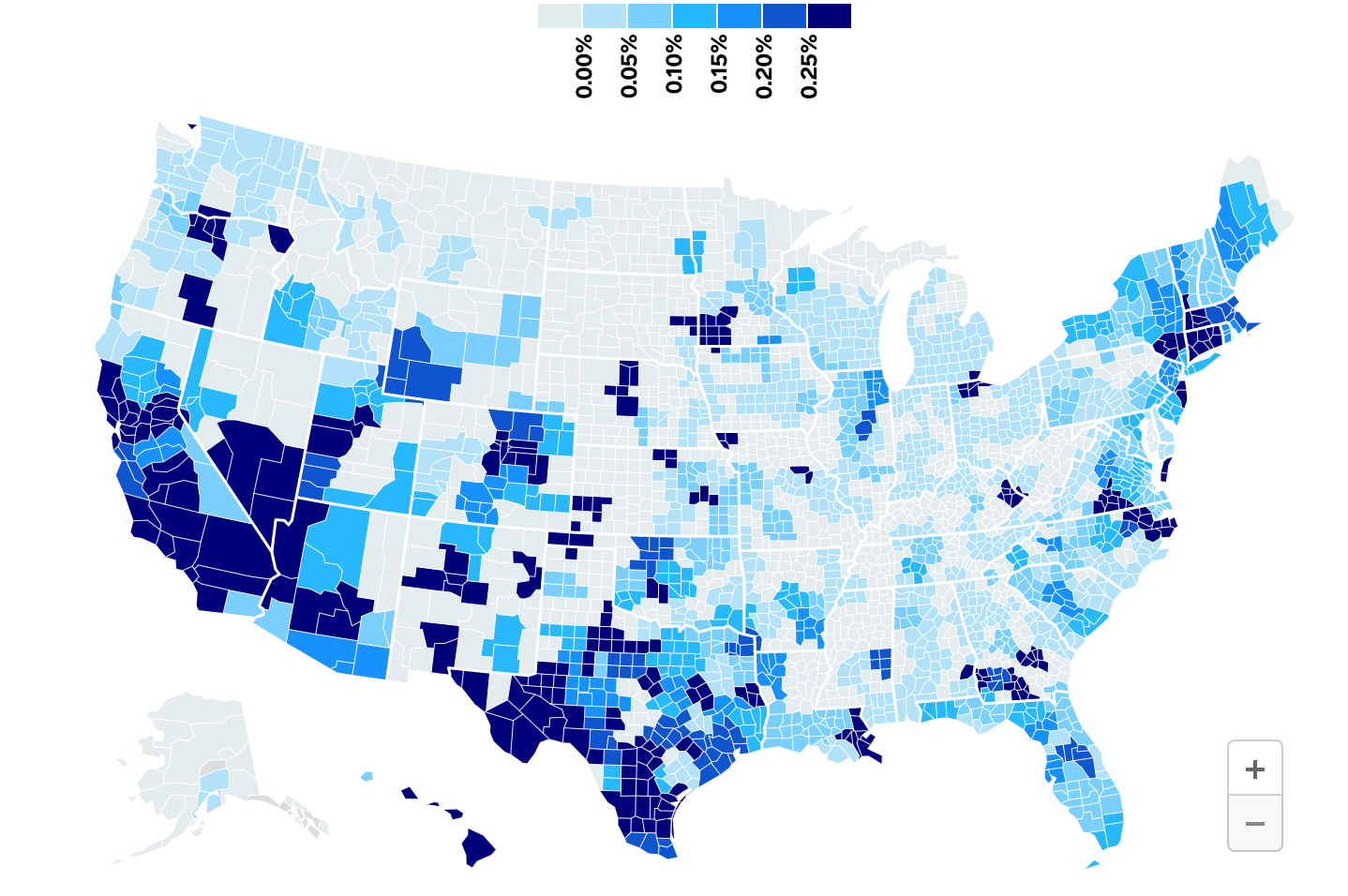

“America has a shortage of skilled construction workers of any kind,” said Baird. Finding skilled construction workers who know how to install heat pumps, solar panels and transmission lines is especially challenging, with more electricians retiring each year than are replaced, according to the National Electrical Contractors Association. Rewiring America, an electrification nonprofit, estimates that the country needs a million new electricians to complete the new wiring needed for the energy transition.

“The pipeline for new electricians has been too narrow for too long,” said Rewiring America CEO Ari Matusiak. By his organization’s estimates, over a billion machines will need to be installed or replaced across American households over the coming decades, from breaker boxes to rooftop solar.

“The scale that is needed to meet the moment when it comes to our climate goals—but also to deliver savings to households and to reinvest in our communities—is pretty massive. And that requires people who know how to do that work,” Matusiak said.

Sam Steyer is the co-founder and CEO of Greenwork, a startup that connects clean energy developers with local contractors. Like Matusiak, he is intimately acquainted with the labor shortage in clean energy, a reality which he partly attributes to negative messaging about skilled trade work to Millennial and Gen Z workers.

“If you look back ten years, even, everyone was saying, ‘Oh, everything’s going to be replaced by automation and globalization, and the only path to a strong economic future is college,’” Steyer said. “I think we’re suffering the consequences of that now.”

Baird and his colleagues designed the Civilian Climate Corps program specifically to address these shortages. The program recruits trainees (or, as BlocPower prefers to call them, “members”) from low-income areas identified as having high rates of gun violence. It typically offers one month of workplace etiquette and business communication classes followed by about two months of technical training, which includes low-voltage electrical work, heating, ventilation, and air conditioner (HVAC) installation and workplace safety training. Most members then move on to on-site apprenticeships.

According to BlocPower, over 400 Civilian Climate Corps participants have secured jobs in related fields, and 62 percent have completed OSHA training. And perhaps most significantly for members, over 81 percent of whom were previously underemployed or unemployed, they get paid $20 per hour during their training.

This fall, BlocPower opened two training hubs in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn and the South Bronx. In October, Mayor Eric Adams announced a $54 million expansion of the program, which will allow 3,000 more New Yorkers to participate in the year ahead.

Policymakers in Washington have been pushing for a federal civilian climate corps for years. Early in his administration, President Joe Biden called for a program “to mobilize the next generation of conservation and resilience workers,” and Democratic lawmakers have introduced legislation calling for the creation of a national civilian climate corps. Funding for such programs was ultimately dropped from the final version of the Inflation Reduction Act, but BlocPower hopes its program can “serve as a model for future national programming,” according to a spokesperson.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.BlocPower is in the early stages of bringing its job-training program to cities like Buffalo, Denver and San Jose, according to a BlocPower spokesperson.

Cities like Ithaca, Philadelphia and Menlo Park, California have tapped the company to help electrify their buildings. Menlo Park has the ambitious goal of electrifying 95 percent of its existing buildings — about 10,000 of them — by 2030.

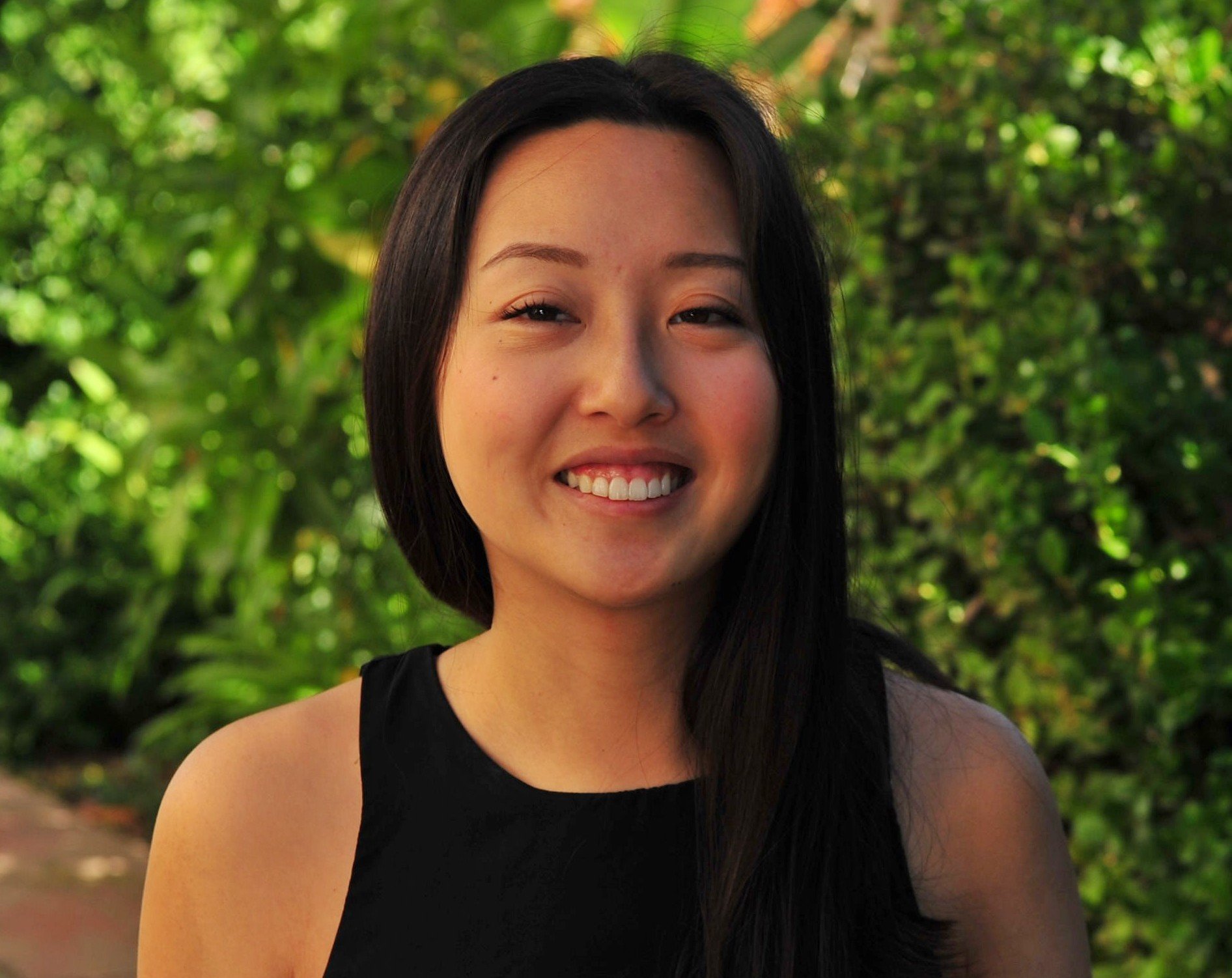

“One of the reasons we chose BlocPower is they’re very much aligned with our goals to focus first in areas that are predominantly communities of color, where the folks have been left out of energy innovations and need good-quality, long-term jobs,” said Angela Evans, Menlo Park’s environmental quality commissioner, who’s responsible for the city’s electrification program.

Though it’s known for being home to tech companies like Meta, Menlo Park is deeply segregated with large pockets of poverty and unemployment, especially in formerly redlined neighborhoods, Evans said. Menlo Park enlisted a local organization to build out its own job training program and plans to select its first cohort of 20 participants — primarily women and people of color — in early 2023.

“We absolutely have the tech, and we know that [electrification is] more efficient than gas, but it’s finding the folks who can do this and who are willing to do it,” Evans said. She’s spoken with quite a few “first-movers” who are eager to electrify their homes but are having a tough time finding available contractors.

Evans said that the city is raising funds to pay participants a comfortable living stipend; the state of California recently granted Menlo Park $4.5 million for its electrification program, part of which will be used to support job training, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has also committed $75,000 to workforce development efforts. The training program will also offer onsite childcare and other benefits, Evans said.

Menlo Park’s program has not yet launched, but Evans said she is already getting calls from other cities across the country, including Chicago and Denver, interested in learning about Menlo Park’s decarbonization and workforce development efforts.

“My genuine hope is that not only will building electrification scale in cities throughout the country, but that we’re going to create good quality, clean energy jobs while we do it,” she said.

For Baird, it’s not just about training low-income communities for good-paying jobs. He wants to ensure they’re also able to get the same energy upgrades their wealthier neighbors have. If BlocPower can help increase the nation’s labor supply, it will reduce the cost of electrification for everyone, he reasons.

Clark, who is now in his second year in the program and helping BlocPower mentor new members, said he’s become a green-jobs evangelist and hopes to excite friends and families about opportunities in the burgeoning field. “The only reason people are hesitant about it is because they don’t understand it. They don’t know about green jobs,” he said.