Two weeks ago, Washington State took a major step toward shutting off the tap for companies that want to haul away its spring water and sell it around the world. The state senate passed a bill that would prohibit companies like Crystal Geyser and Nestlé from extracting, bottling and selling water from spring-fed sources. If enacted, it would be the first state law in the nation to declare that “any use of water for the commercial production of bottled water is deemed to be detrimental to the public welfare and the public interest.”

Governor Jay Inslee hasn’t taken a position on the bill, but observers say he will likely support it, setting a precedent for other states like Maine and Michigan that have pushed back against water bottling operations in recent years.

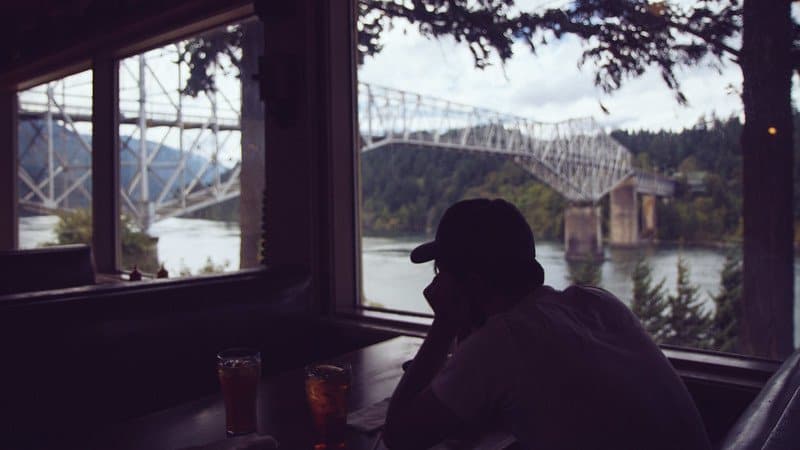

Washington’s law would be the toughest restriction on water bottling operations in the U.S. so far — but it wouldn’t be the first. Across the Columbia River from the state’s southern border, Hood River County, Oregon, won an improbable victory against a Nestlé bottling operation in 2016, setting the stage for efforts like the one in Washington today. Hood River County’s fight against Nestlé took a decade, but in the end it stopped the company from opening up a facility in the small town of Cascade Locks and banned commercial water bottling in the county entirely. The lessons of that fight offer a roadmap for similar efforts elsewhere.

An extractive industry

Despite the snowy mountain peaks and sparkling waterfalls that adorn their labels, nearly two-thirds of all bottled water sold in the U.S. come from municipal tap water. Not only is this water no safer or purer than water from the faucet (tap water is actually tested more frequently) it is 2,000 times more expensive. In addition, the bottled water industry creates millions of single-use plastic bottles that will never be recycled. In 2016, four billion pounds of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) plastic was used for bottled water production.

But it’s bottled water from spring-fed sources that can have biggest ecological impacts. “Bottling spring water can be disastrous to the water table because the company sucks a large amount from a small source,” says Julia DeGraw, who was the senior Northwest organizer at Food & Water Watch during the decade when Nestlé was trying to open a bottling facility in Cascade Locks.

DeGraw says that communities in Mecosta County, Michigan have seen their wells run dry, their springs stop flowing and their fish die off because of Nestlé’s aggressive water pumping operations. A spokesperson from Nestlé Waters North America does not directly deny this, but points to data from Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy showing that the state’s nearly 40 bottled water companies account for less than .01 percent of water used in the state.

Hood River County’s fight against Nestlé began back in 2008, when the multinational company approached Cascade Locks with plans to open a $50 million bottling plant that would have extracted more than 100 million gallons of water a year from Oxbow Springs, which feeds a salmon hatchery.

DeGraw remembers those early days clearly. “We were the lead organization… really early on when we were trying to build a coalition,” she says. That coalition ended up being big, a fact that was key to the effort’s success. It included not just environmental groups like Food & Water Watch and the local Sierra Club chapter, but also public sector unions, Native American tribes, activist nuns, pro-bono lawyers, ultra runners, a hunger striker and ordinary people turned activists.

Also critical was the fact that although the effort was grassroots, it was also well-resourced. Food & Water Watch put money behind the campaign, hiring DeGraw to be the local organizer and helping to pay for the county ballot measure. And in 2012 the Crag Law Center donated its services, filing two protests challenging the Oregon Water Resources Department’s (OWRD) approval of Nestlé’s water exchange permit.

The broad reach and resources of the coalition, which named itself Keep Nestlé Out of the Gorge (KNOG), allowed it to confront the company’s U.S. water division, which has a pattern, the organizers say. They claim it seeks out economically distressed towns like Cascade Locks, which was once a boom town when the timber industry was thriving. In 2010, the town had a median income of just $42,917 and an unemployment rate of 15.5 percent, according to data from the U.S. Census.

“When the mill closed down, it really had a profound effect on the economy,” says Aurora del Val, a retired English teacher who got involved in the campaign to keep Nestlé out. “Cascade Locks is a town that has the profile that I think a lot of these water companies are looking for. And they’re saying all the right things. The Nestlé guy would shake hands with all the business people and gave money to the food bank. He made all these promises. There is a real standard way that they operate in a small town.” Nestlé’s spokesperson confirmed that the company makes significant economic contributions in areas where they operate. “We support many community organizations, locally and nationally, through donations of water, food, supplies, and money,” he wrote via email.

In Cascade Locks, Nestlé promised jobs and economic prosperity while playing down potential environmental consequences, and local officials took it at face value, del Val says.

“It’s kind of like the tobacco industry saying ‘Don’t worry, it doesn’t give you cancer!’” she continues. “The water plant might’ve provided a few jobs locally, but in terms of — for the larger economy — it would’ve put the water supply at risk.”

Resistance coalesces

Concerned about the negative repercussions — depleting groundwater that farmers and residents depend upon, siphoning off the cold creek water that’s essential for fish habitat — del Val started to talk to her neighbors, many of whom were also concerned. In the spring of 2015, she helped found a group called the Local Water Alliance, eventually becoming the group’s campaign director. Even though she calls herself a “reluctant activist,” del Val went door-to-door and talked to Democrats, Independents and Republicans alike.

In Cascade Locks, she and others were able to persuade long-time residents and independents Kathy and Bob Tittle, who own the Chevron station in town, as well as Joseph Shelley and Lynn Pruitt — a Libertarian and Republican, respectively — who felt so strongly about the campaign that they allowed their photos on the Local Water Alliance’s materials. In Odell, in the heart of orchard country, Butch Gehrig, a registered Republican, endorsed the Alliance’s campaign, too. “Water matters, and it doesn’t matter which political affiliation you are,” she says.

The Yakama Nation opposed the bottling plant at around the same time. Chairman JoDe Goudy spoke on the steps of the Oregon Capitol saying that the Yakama Nation would sue the state of Oregon if Nestlé was authorized to bottle water from Oxbow Springs. The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and Umatilla and Nez Perce tribes also sent Governor Kate Brown letters opposing the bottling facility and critiquing the process.

“Our natural resources are important and we can’t be extracting them,” says Carina Miller, who was a member of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs’ tribal council at the time. Miller says that tribal treaty rights were disregarded when the Nestlé deal was set into motion, and was troubled that this wasn’t what motivated Governor Kate Brown’s late-in-the-game decision to oppose the deal. On the other hand, Miller says, the fact that area environmentalists and conservative white farmers alike recognized that tribal people needed to be at the table was huge. “To go and have shared values — just that there was an acknowledgement that tribes should be included. That was a win.”

Even though Nestlé spent $105,000 to oppose the Hood River County Water Protection Measure — more than double what backers of the measure raised — it passed in May 2016 by nearly 70 percent. “It was democracy in action,” del Val says. “The power of the vote was pretty inspiring. Even though this is a real dark time, people do really make a difference.”

Even so, perhaps because Governor Brown hadn’t taken action, Nestlé, Cascade Locks and the ODFW continued to pursue a water rights swap, in violation of the voter-approved measure. (At question was whether a county government has the authority to tell a city government what it can and can’t do with its resources.) After a new round of emails and phone calls from local residents and a damning story from a local news affiliate, Brown finally told ODFW to halt its water exchange in October of 2017, putting the kibosh on the Nestlé facility for good.

Today, business is booming in Cascade Locks, according to del Val. A Basque cidery called Son of Man recently opened, sharing space with two natural winemakers. Thunder Island Brewing just broke ground on a 10,000-square-foot facility on the main street. And Renewal Workshop, a startup that takes discarded apparel that would normally go into the landfill and transforms it into new products or upcycled material, opened in 2016. “Those are the kinds of companies that are opening here,” says del Val. “They’re green and sustainable… and they’re hiring!”

Now Hood River County is passing on the lessons it learned from its epic battle. DeGraw and del Val have recently shared tactics and strategies with resident-turned-activists in Randle, Washington, who have been fighting a similar effort by Crystal Geyser. “You don’t have to reinvent the wheel,” says del Val. “Not everyone involved is a career activist. We’re just ordinary people who care.”