The following is an excerpt from “Solved! How Other Countries Have Cracked the World’s Biggest Problems and We Can Too” by Andrew Wear.

Although it’s a rather agreeable place, there’s nothing particularly exceptional about Samsø Island at first glance. Located off the coast of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula, this former Viking outpost is home to a traditional farming community, best known for producing the country’s first potatoes each year. After arriving by ferry, as you travel around the largely flat island — perhaps by bicycle — you’ll see cows and sheep grazing leisurely, weathered farmers driving tractors and the occasional farm dog.

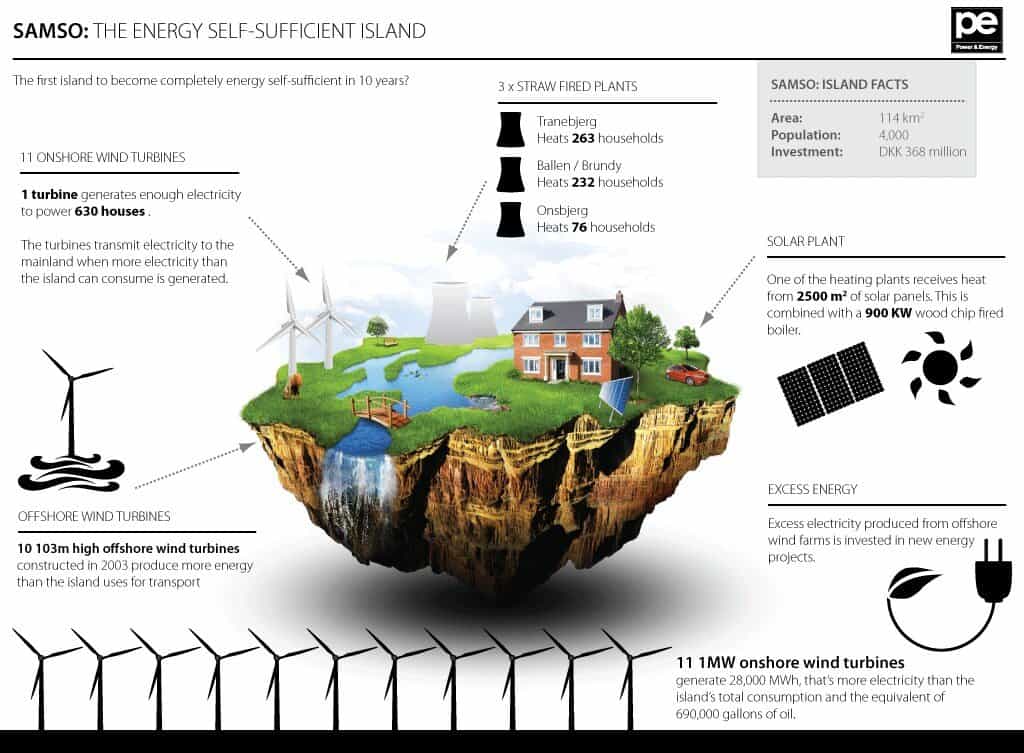

This very ordinariness is what makes it so remarkable that, for the past 20 years, Samsø has been a world-leading green energy community. All of Samsø’s electricity comes from massive community-owned wind turbines, while biomass boilers burning local straw meet 70 percent of the island’s heating needs. Each of Samsø’s 3,724 residents now emits an average of negative-3.7 tons of greenhouse gas per year.

The success of Samsø Island is indicative of broader efforts in Denmark to address climate change. It ranks second in the world (behind Sweden) on the Climate Change Performance Index, and it has succeeded in halving its per capita greenhouse gas emissions over a relatively short time frame. However, Denmark is determined to go much further. With a remarkable political consensus, it has committed to energy agreements that by 2030 will see 100 percent of its electricity generated from renewable sources.

The experience of Samsø Island, and Denmark as a whole, shows that it’s possible to almost eliminate carbon emissions using existing technology — we do not have to wait for some indeterminate future point in which new technology comes to market. It also shows that local communities, with the right leadership and supported by national policy, can drive real change.

Overcoming skepticism

In 1997, Samsø was struggling. The abattoir — the largest private employer on the island — had just closed, taking with it 100 jobs. Like many rural communities around the world, the island’s population was both aging and declining. The Danish government, looking for a showcase opportunity to demonstrate that the 21 percent emissions reduction target in the Kyoto Protocol was possible, launched a national competition to find a Danish Renewable Energy Island. It sought to identify the island or area with the most achievable plan for becoming 100 percent self-sufficient in energy production. The Danish Energy Authority would provide funding to aid the transition.

The national government also wanted to see civic participation. Local businesses, the council and community organizations all had to support the plan. Although the focus was on using existing available technology, the government was interested in exploring new ways of organizing, financing and owning the technology.

The winning location was expected to function as a demonstration of Danish renewable energy expertise that could be displayed to the rest of the world. Samsø’s municipal government submitted an application, and in 1998 it won, beating three other islands and a peninsula.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The prize included funding for a coordinator to develop a ten-year plan. This role piqued the interest of Søren Hermansen, director of the Samsø Energy Academy. “Because I had been around for a little while, and I made my voice heard every now and again at meetings, I was asked if I wanted to be the manager of the Energy Island. I accepted the position, just to give it a go, and had to keep on farming. But it very soon turned into a full-time job, so for the last twenty years I’ve been working in this field.”

The competition win was not like “a golden ticket,” Hermansen says. “We didn’t get a lot of money for it. We had to do it with the same conditions that any community in Denmark had at that time.”

Initially, the project met with some community resistance. “People were like, ‘Thank you but no thank you. It sounds really expensive and complicated and we can’t do this alone.’” To engage the somewhat skeptical locals, Hermansen spent a lot of time talking with them. If a section of the island was holding a town meeting or an event, Hermansen would turn up, bringing sandwiches or beer. He’d go door to door, talking with people in their kitchens.

The plan was to quickly transition the island to wind power. By 2000 — just two years after winning the competition — 11 wind turbines were due to be installed, each with capacity to generate one megawatt of power.

The idea was not universally beloved. Residents had concerns about the potential noise and visual impact of the turbines. The challenge for Hermansen and his team was to bring around the local community. They undertook extensive public negotiations over the location of each turbine.

A crucial step in gaining community support was to invite locals to own the turbines. As Samsø Island’s website notes: “Windmills are much prettier when you are a co-owner, making money when the wind is blowing.” A decentralized structure was created, with cooperatives being formed, or shares being sold in each turbine. Hermansen says that “everybody who lives in the neighborhood had a chance to invest their money in the turbines, giving a sense of local ownership that was strong enough to overcome the flip side of the turbines.” Locals signed on to this scheme enthusiastically, contributing enough through cooperatives to purchase two turbines, while individuals purchased the remaining nine. These 11 turbines generate enough power to make each of the island’s 22 villages self-sufficient.

In 2002, to offset emissions from the island’s cars, tractors and ferries, a further ten offshore turbines were installed, with a combined capacity of 23 megawatts of power. These turbines are located in relatively shallow water, with foundations fixed in the ocean floor. Sub-sea transmission cables connect the turbines to the electricity grid.

Offshore wind farms such as this are increasingly the norm in Denmark, as its ocean areas have strong and consistent wind patterns, and farms can be larger while generating less visual impact and noise for residents. Turbines are also often easier to install offshore, since ships can carry the massive components, which are difficult to transport on land.

Two of Samsø’s offshore turbines are cooperatively owned. The municipality owns a further five turbines, which generate income that the local government can reinvest in sustainability measures. This includes smarter methods of heating and incentives for the purchase of electric cars.

Samsø is cold in the winter, with an average January maximum of three degrees Celsius (37 degrees Fahrenheit). To address the island’s heating needs, three plants were installed between 2002 and 2005. These burn biomass, mostly local straw, and supply 70 percent of the island’s heating requirements. Many of those not on district heating have replaced old oil furnaces with solar collectors or biomass burners of their own. Like much of the world, electricity use on Samsø has increased over the past two decades, as people use more appliances more often. However, because of the emphasis on retrofitting old houses with energy-efficient electric heat pumps, and thick insulation made from recycled materials, consumption has decreased more than 20 percent since 1998.

Samsø also has the highest number of electric cars per capita in Denmark. The municipality changed its fleet to electric vehicles, powered by solar panels.

Samsø continues to make progress in reducing emissions and remains a shining example of a community-based response to climate change. But most compelling is that much of the technology underpinning Samsø’s energy shift is common. There are now hundreds of thousands of wind turbines spinning around the world, producing about six percent of the world’s electricity demand. The story of Samsø is not of new technology; it’s about how a concerted effort and an engaged community can use existing technology to eliminate carbon emissions. This proved possible when people saw that addressing climate change aligned strongly with other community interests, such as economic development.

The experience of Samsø Island is instructive. This small rural community has shown that with leadership and commitment, climate change is a challenge that we can take on. It has inspired community efforts across the world, such as Hepburn Wind, a community-owned wind farm in Australia, and Sustainable Molokai, a community-based sustainable energy group in Hawaii.

Hermansen’s roots will remain on Samsø Island, though. He wants to be there to help the island to achieve its next goal: complete independence from fossil fuels by 2030, 20 years ahead of the rest of Denmark. “We plan to get rid of oil completely by 2030,” Hermansen says. “This is very ambitious too, because we still have tractors.”

As a step towards this goal, the Samsø municipality recently bought a large new ferry, capable of transporting 600 passengers and 140 cars. In a first for Denmark, it has a dual-fuel engine, which makes it possible to run on liquefied natural gas rather than heavy fuel oil, reducing carbon emissions significantly. However, it can also run on locally produced biogas. It’s quite possible that if you visit Samsø in future, you’ll arrive on a ferry powered by methane produced from household waste or pig manure. And you may even run into Søren Hermansen, with his mischievous smile.