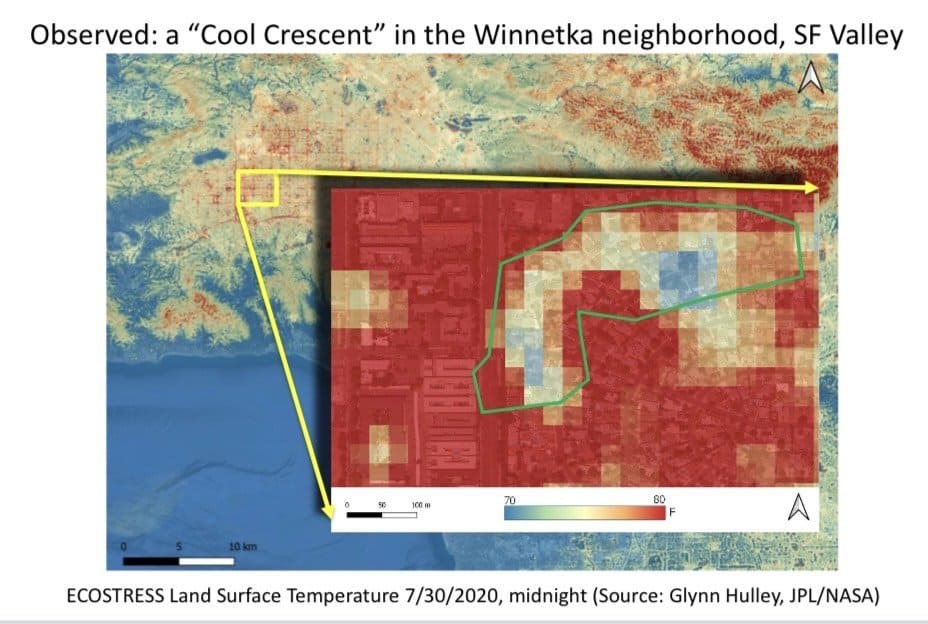

When the scientists aboard the International Space Station direct their thermal camera at Los Angeles, standing out from the sweltering red and orange blob is a crescent of cool, blueish white deep in the San Fernando Valley.

Greg Spotts, Chief Sustainability Officer of the City’s Bureau of Street Services (Streets LA), is proud of these wintry-looking pixels — not many people can say their work is visible from space. In this area, the center of the Valley’s Winnetka neighborhood, the pavement has been painted with a special reflective coating. “The locations near the cool pavement were, on average, two degrees Fahrenheit cooler than the surrounding area,” Spotts says.

“Previously, our measurements were focused on measuring the surface temperature of the roadway itself, which showed a difference of 10 to 15 degrees Fahrenheit on hot days,” he adds. The satellite thermal camera is significant, however, because it shows that the special cooling pavement not only lowers the temperature on the road, but “produces a cooler neighborhood” in general.

Ten streets in ten neighborhoods have been treated with this cooling paint, and the next phase has just started: This month, bright yellow trucks will roll through West Hollywood and South L.A. to spray white coating on ten streets. “We have identified 200 city blocks across eight underserved neighborhoods for the next phase of urban cooling.”

The record heat waves that scorched the earth from Arizona to Antarctica this year will only get worse, and cities, where heat radiates off buildings and asphalt, will bear the brunt of this heat. “We’ve built our cities like ovens,” Spotts says. “We’re largely using the same materials we have been using since World War II. We need a large-scale change.” According to NOAA, highly developed urban areas can experience mid-afternoon temperatures that are 15 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than surrounding, vegetated areas. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions tackles the root cause, but in the meantime, cities are looking for ways to lower the temperature. One of the cheapest is to paint roofs and streets white.

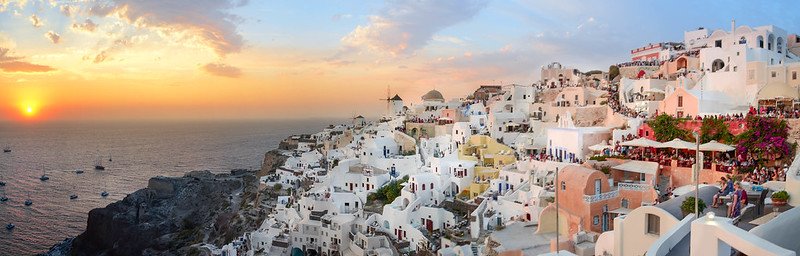

The Greek islanders of Santorini, with their whitewashed earthen buildings, were on to something: white surfaces can keep a densely populated area cooler. To this end, New York City has added white, reflective coatings to more than 10 million square feet of rooftop over the last decade. And Los Angeles has installed more than 30 million square feet of cool roofs as part of its new building code. These days, when you visit certain parts of L.A., such as Winnetka or Echo Park, you’ll notice the black asphalt changing to a light grayish-white on more than 50 city blocks.

“At first we thought it might reduce the use of air conditioning and thus help lower associated carbon emissions,” Spotts says, “but we’ve learned that the main driver for this work is public health. We are the only city in the U.S. that records heat-related deaths and emergency room visits in winter.” While Los Angeles is not America’s hottest city (that would be Phoenix), and its climate is tempered by ocean breezes, the heat still carries deadly risks. “We can have hot, humid air in January, and people aren’t prepared,” Spotts knows. “In neighborhoods around the northern rim of the city, the number of days above 95 degrees (35 Celcius) is likely to double, and they already have 40 or 50 of these hot days every year. Can you imagine having 100 days a year of 95 degrees or above?”

For all the concern about worsening hurricanes, floods and tornadoes, severe heat kills more Americans than any other weather event. A recent UCLA study found that higher temperatures even increase the risk of injuries — the researchers estimate that high temperatures already cause about 15,000 injuries per year in California.

In 2015, as part of L.A.’s “Green New Deal,” Mayor Eric Garcetti pledged to lower the city’s average temperature by three degrees over the next 20 years. “Cool Streets LA” is part of the effort, piloting six cool-neighborhood projects in vulnerable communities by 2021 and ten by 2025. “We were the first jurisdiction in California and perhaps even the U.S. to install cool pavement coating on a public street,” Spotts says. Painting streets is clearly not enough: Key goals include increasing tree canopy in areas of greatest need by at least 50 percent by 2028. “Rising temperatures put our local communities on the front lines of the climate crisis,” said Garcetti. “Cool Streets LA is about taking action in ways that will make a real and direct impact on people’s daily lives.”

Spotts, formerly a talent manager in New York who co-founded the Shortlist Music Prize and served as a talent manager for record producers and engineers on projects for Seal, Alanis Morissette and Jewel, enjoys talking with the residents who often come outside to inquire about the new pavement. “Every single resident says that they noticed their surroundings are getting hotter — every single one.” Spotts was originally worried residents might complain because dirt and tire marks are more visible on the brighter pavement, “but that hasn’t happened.” Surveys show that residents appreciate the program. “It feels less hot,” reads one of their comments. “Now, me and my family come out on weekends, and lay blankets out on the front yard and spend the time outside… Since the application of the cool pavements, a lot of people from other neighborhoods walk in our neighborhood.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.It’s not as simple as whitewashing everything. The right materials and strategic placement are critical, otherwise reflective coating can even have the opposite effect. A recent study by Purdue University found that a new “ultra-white” reflective paint is the most effective — it bounces 98 percent of the sunlight back into space — but it contains a rare mineral and is not environmentally friendly. Some cool pavements require enough resources and carbon-intensive production that their climate benefits don’t pencil out. Cost is another issue: Reflective paint is about 50 percent more expensive and probably needs to be reapplied every three to five years. (On the other hand, heat waves are costly, too.)

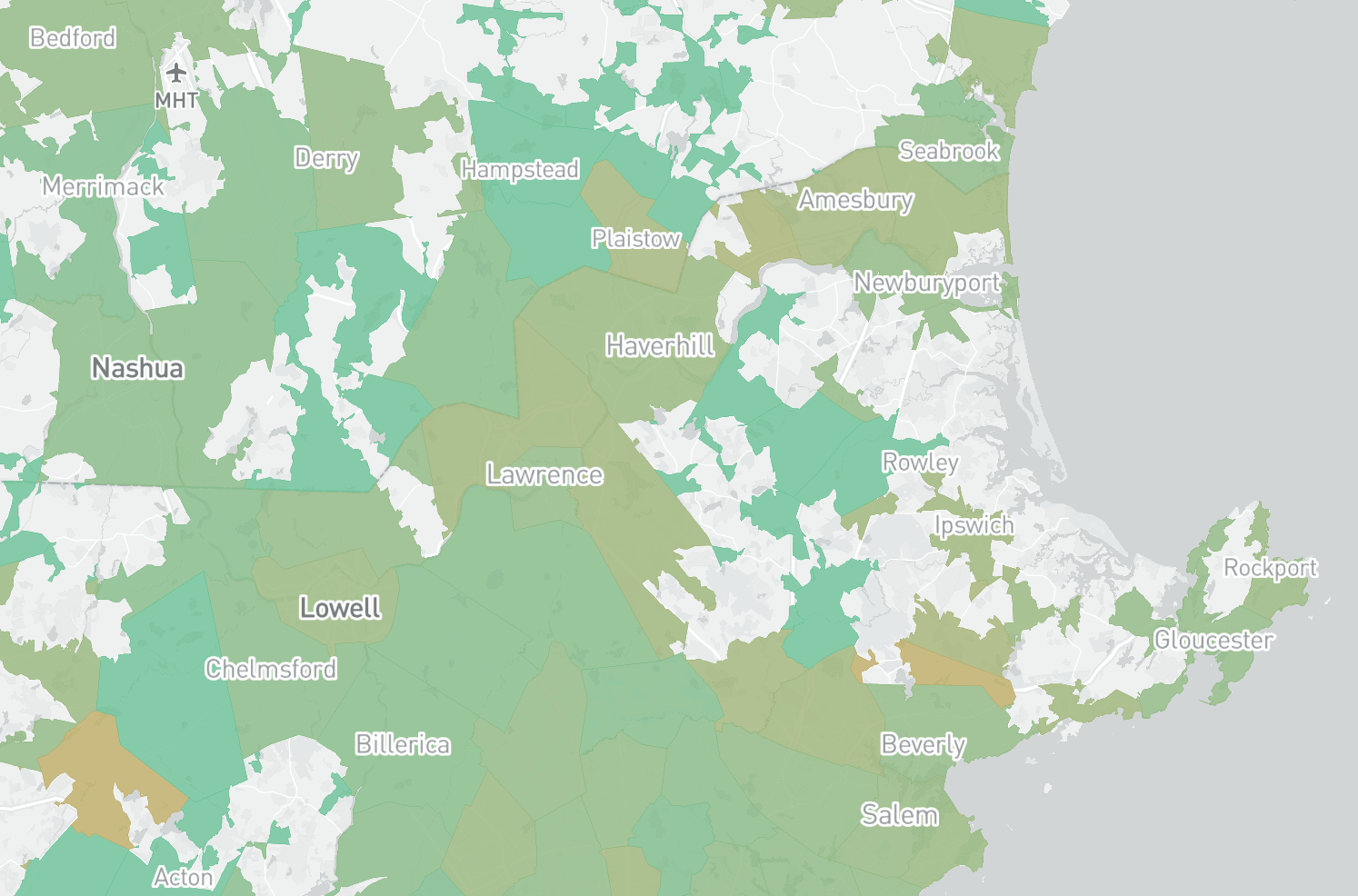

Also, urban heat is not distributed equally. Black and Hispanic residents in U.S. cities suffer nearly double the exposure to urban heat islands. “There are tremendous equity challenges in neighborhoods,” Spotts acknowledges. “These are neighborhoods with overcrowded housing, also often older, substandard housing.” Spotts uses the “Climate-Smart Cities” tool by the Trust for Public Land, a conservation organization, to analyze the city’s hot spots, and a tree canopy tool by Google Earth. “All the tools identified the same neighborhoods: 200 city blocks where we will be installing cooling pavement over the coming ten months.”

He believes that urban cooling supports three principles at once: sustainability, equity and workforce development. “Because if you are transit dependent, and it’s too hot to get to your bus stop and wait there, then you are not going to be well prepared for your workday. Mobility and heat are now linked.” To address the manifold issues, the “Urban Cooling Committee” within Streets LA brings together engineers, landscape architects, and pavement and tree specialists to find the best approach for what Spotts calls “holistic multidisciplinary thinking.”

L.A. isn’t just looking at its own turf: the city is partnering with places such as Phoenix, Tucson and Philadelphia. And 25 U.S. cities have formed a “cool roadways partnership” to exchange information about best practices, maintenance and cost. “We’re trying to leverage the purchasing power of these 25 cities instead of each city following their own effort,” Spotts says. “I think that’s going to end up being a game-changer in the near future.”