Working as a creative in Portugal’s video and animation industry, Vanessa Oliveira quickly became used to last-minute demands from clients.

“There were always crazy deadlines,” says the 30 year old, who is based in the northern city of Porto. “I would get calls at 8 p.m., when I was at home already, saying: ‘There’s this project and you have to deliver it tomorrow morning.’”

One time, when working for a large creative studio, Oliveira made an exception and refused to pull an all-nighter. “The next day at the office, they told me: ‘Because you went home, all your colleagues had to work an extra hour,’” she says. “Sadly, these conditions are very common in the creative area. Employees are afraid to say no.”

But an amendment to Portugal’s Labor Code, passed into law in November, could put an end to these practices and protect the work-life balance of citizens by introducing a so-called “right to rest.”

Under Portugal’s new laws, proposed by the ruling Socialist Party, workers will have the right to at least 11 consecutive hours of “night rest,” during which they can’t be contacted by their employers unless there is an emergency. Employers with more than 10 employees now face criminal sanctions if they message, phone or email their workers outside of working hours. However, Portugal’s parliament stopped short of voting for employees to be able to turn off all work devices when off the clock.

Responding to the rise of remote working, under the new law companies will also need to contribute to staff’s work-from-home expenses, such as internet and electricity. Bosses will also be expected to meet with staff in person at least every two months, to prevent those working outside of the office from becoming isolated. And the right of parents to work from home, previously reserved for those with children under four, will be expanded to include those with children up to eight years old.

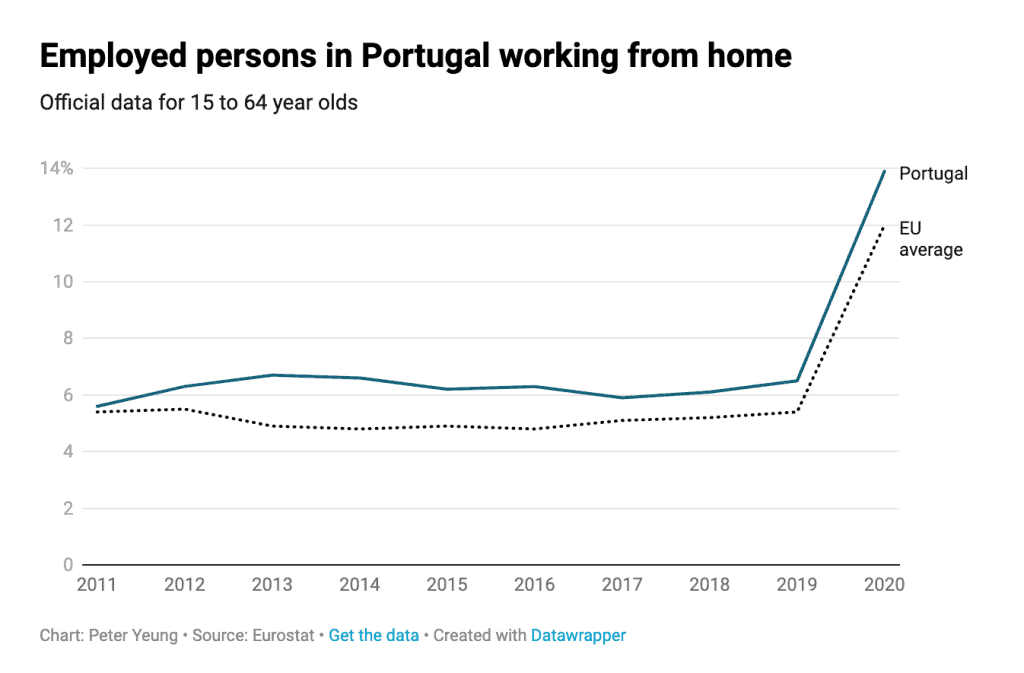

The growing digitalization of the workplace and, more recently, the pandemic-induced spike in remote working, has put a huge strain on workers like Oliveira. According to the EU agency Eurofound, the proportion of people in the EU working remotely rose from five percent in 2019 to 48 percent in July 2020. That rise appears to be part of a long-term trend. Research by Gartner has estimated by the end of 2021, 32 percent of the global workforce will be remote workers.

“For me, it was really difficult in the beginning to disconnect,” says Oliveira, who is now freelance. “When the pandemic started, since we were at home we were working more. At one point, I felt like I was only working and sleeping.”

Catarina Tavares, international secretary at the trade union UGT-Portugal, says that the pandemic has made updating workers’ protections for the digital age a priority.

“This pandemic has not been helpful for working conditions,” she says. “It’s been a heavy duty on these workers. So I think the law is likely to make a difference.”

Portugal’s law, one of the boldest moves to modernize workers’ rights to date, is part of a wider movement in Europe. France, Spain, Germany and Italy have enacted similar protections, and in January the European parliament voted overwhelmingly in favor of a resolution to propose a pan-European “right to disconnect” law.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.While data on the impact of these measures remains limited, research by Eurofound suggests that they are influencing corporate cultures. German chemicals company Evonik, which in 2013 independently introduced right to disconnect rules for its 32,000 staff, found that between 2013 and 2020 the percentage of emails sent after 8 p.m. decreased from 13 percent to six percent and those sent over the weekend from two percent to one percent. In addition, interview respondents said the policy “has contributed to improvements in work-life balance,” thanks to a greater awareness of flexible working and the risks of constant connection.

UGT-Portugal’s Tavares says work from home protections could also mean greater gender equality, since women are more likely to take on the burden of childcare. However, she does have some concerns about Portugal’s law. It will take months or years for companies to properly adapt to the new regulations, she says, and adherence will be difficult to monitor and enforce.

“There are always challenges,” she says. “You can’t go into people’s homes and check if they have good working conditions. But in terms of compensation for working from home and the need to have consensus, I think it is a really important law.”

David Carvalho Martins, an expert in Portuguese labor and employment law and founding partner of the labor law firm DCM Littler, is more sanguine about the impact that the law could have. “This is not a massive change to the current system,” he says. “In most cases it’s just a rebranding of what we have already.”

For instance, the ban on contacting employees during an 11-hour “rest period” is not the same as preventing them from working during those hours, according to Martins. And in professions that already have “working time exemptions” or those that require employees to be on call, such as finance, tech and emergency healthcare, little will change. “They can still be contacted, but this must be justified by the employer,” he says.

Oliveira has similar concerns about those emergency exceptions. “It is sad that you have the right to disconnect, except if something urgent happens,” she says. “The concept of urgency to the company could be up to them to decide.”

Yet there is consensus over the symbolic impact of the “right to rest” law, and how it could mark a societal shift. “Now it’s a worldwide topic,” says Martins. “It could be the first step to change mentalities. It opens up the discussion.”

Oliveira agrees. “People really have to know when to disconnect now,” she says. “Even now, if I receive an email at 9 p.m., it’s still difficult for me not to look. If the law changes that mindset it could be really important for so many people.”