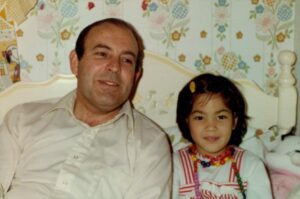

When Jay Newton-Small moved her father Graham, who had Alzheimer’s, into an assisted living facility, he was no longer able to tell or remember much of his life story. His daughter was asked to fill out a detailed questionnaire about his life, but she wondered, who would remember 20 hand-written pages for each of the 100-plus residents in that community? Tapping into her experience as a longtime Time magazine correspondent, Newton-Small tried a different approach: she typed up his story on one page for his caregivers and pasted it on the walls.

Newton-Small says that this simple act of storytelling transformed his care. Born in Australia, her dad had lived an adventurous life on three continents as a United Nations diplomat. “From the food servers to the podiatrist who clips his toe nails, none of them knew much about him,” she says. “Until they read his story, they treated him like a checklist, you know, get him dressed, get him shaved, get him fed. Each of these things is a check, but when you find some form of commonality, it changes your whole relationship.”

For instance, two of his caregivers were Ethiopian and were fascinated to learn that Graham Newton-Small had lived in Ethiopia for several years during his career with the UN, and they wanted to hear all about his encounters with emperor Haile Selassie. “They became his champions,” Jay Newton-Small says. “They would sit with him for hours and ask him what it was like back then, and even though my dad didn’t remember what happened last week or last month, he still remembered what he had done in his twenties. He hardly spoke anymore but asking him about these memories was the way to get him to speak.”

Newton-Small found the experience so transformative and so many families approached her about doing the same for their family members that in 2017, she founded MemoryWell, a platform that allows patients and their families to create short life stories with the help of professional writers. The goal is to enable caregivers to relate to their patients. Families can contribute by uploading photos and memories. The initiative has received several noteworthy awards, including the Not Impossible Healthcare Breakthrough Award in 2021.

Though the pandemic with its caregiving crisis put a huge dent in the endeavor — most caregivers were too overwhelmed to think about anything beyond the demands in front of them — MemoryWell has produced about 1,500 life stories since its start and currently contracts with more than 1,000 freelancers. Most stories run 500 to 700 words.

Some families sign up themselves, some senior homes employ MemoryWell’s services, and several providers reimburse the cost for dementia or hospice patients as part of patients’ care. Costs range from $75 to $300, depending on the level of time and research required.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Each life story has a quick summary for caregivers to get an overview at a glance, and then the platform offers different access levels for caregivers and families to get into the details. “Many senior living places have you fill out a questionnaire like I did when I moved my dad,” Newton-Small says, “but this Q&A is hard to digest, especially for busy caregivers who are on the frontlines and just want to get a quick sense of, okay, who is this person? How can I relate to them? How can I engage them? The more you engage them, the more you keep their brains active, the better their quality of life is, and that’s what you want, right?”

In the early days, Newton-Small wrote the life stories herself. One of the first stories Newton-Small wrote was the mini biography of a retired accountant in an assisted living facility in Iowa who was behaving erratically. Three times a day, an old-fashioned chow bell rang to alert people in the community that food was ready. Whenever that bell rang, the man started accosting people and the staff was at the point of thinking they needed to kick him out. “They tried everything to calm him down, drugs, etcetera, you name it,” Newton-Small says. “Through my writing his life story, they realized he had been a lifelong volunteer firefighter. The bell sounded like the bell in the firehouse and he was trying to evacuate people. They changed the bell to a chime and he was totally fine.”

Newton-Small likes to think that her work “really changed his life, because he was getting very upset three times a day and was potentially going to lose his place in this community over this. It made his life much more peaceful.”

Newton-Small is convinced that the narrative is crucial, and the details that matter are usually quite different from the medical information. “We don’t need to put the date of birth or other information people would want to steal, but it is okay for them to know that a resident loved to pick daisies when she was a little girl, had a cat named Daisy and became a florist.” A separate sheet just for caregivers might inform them about trauma triggers that are too sensitive to publish.

Senior homes find that the patients and families enjoy telling their memories, and that the initiative helps to provide better care, establish closer relationships between caregivers and clients, and surprisingly, lower staff turnover.

Deirdre Heersink heard about MemoryWell when the platform received the Breakthrough Award. As the medical director of Gray Birch in Maine, a senior living facility with 138 residents, she was looking to improve care in the midst of the pandemic.

Staff turnover was 400 percent that year, caregivers were aching under the protective Covid gear, and the rotating staff and the masks made caregiving even less personal. “Patients couldn’t have visitors and the isolation took a great toll,” Heersink recalls. In one unit, they had lost 50 percent of their residents after a Covid outbreak.

Heersink wrote the first five client biographies herself with the help of MemoryWell and was so surprised by the “remarkable” changes they prompted that she found funding for 45 resident biographies. “When people move here, they are often afraid and feel nobody knows them,” she says. “And it’s true. We really don’t know them. The nutritionist asks them about their favorite foods, the social worker is asking social worker questions, physicians ask their set of questions, but there is no place where we draw back and see a cohesive picture of the whole person.”

One resident in a wheelchair had been a successful race car driver, and posting the photo of him next to his race car made the staff realize what a daredevil he had been. “Because of the story they understand him better, so I don’t need to try to constantly explain who he is, and the things that he has done, to the staff,” his sister said.

One hundred percent of staff at Gray Birch said it improved the quality of work, and an overwhelming majority of patients and their families reported back that they felt care improved. “You get a whole picture of them as a person versus just a bunch of medical diagnoses,” one therapist said. “Being in a lot of facilities, this program is phenomenal. It should be everywhere,” an agency nurse reported in her feedback.

“When you ask caregivers why they’re doing this work they’ll tell you it’s all about relationships and connection,” Heersink says. “But it’s also the first thing that gets lost. There are many problems in caregiving. Sometimes we think all the problems are too big and that stops us from doing anything to solve them.” She believes humanizing the residents is at the core: “When people are invested in the people they’re caring for, they go the extra mile for them.”

Some caregivers were able to use information from the biographies to calm patients. For instance, one ALS patient’s favorite song was “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” His Jamaican caregivers would break into song when he got upset, and it would immediately transform his mood.

Jay Newton-Small’s father became difficult and erratic during his struggle with Alzheimer’s. “He was reliving some childhood trauma and became really aggressive,” Newton-Small remembers. She has seen that behavioral issues are rather common with dementia and Alzheimer’s patients, including biting and kicking. “If you tell him, ‘Sir, please calm down,’ it would just enrage him more,” Newton-Small says. But calling him by his childhood nickname, Gray, or showing him photos from his childhood in Australia would calm him. “If you knew the right things to say to him, then he was easy to deal with.”

Another client she likes to remember is a patient who had ALS. “He couldn’t express himself very well anymore and it took him over two hours to tell his story, but he was really insistent, he really wanted to tell it himself. By the end, tears were just pouring from the wife’s face because, she said, ‘This recording is the final gift to our kids, to hear his voice tell his own story and for them to be able to cherish this for the rest of their lives.’”

Usually, the interviews take 45 minutes or less, but Newton-Small and her writers have learned to be flexible.

As a reporter, Newton-Small had covered the Bush and Obama administrations for Time magazine. Her last assignment was covering Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016. When her editor asked her what she wanted to do next, she told him she wanted to write about aging issues. Her editor suggested she cover the White House again instead. “I was getting a little burnt out on DC politics and the lack of solutions,” Newton-Small admits. “Some of the stories I wrote for Time, I wrote for an audience of millions. I might write a story for MemoryWell for an audience of 20 people, but you can really tangibly feel the difference you’re making in people’s lives. To me, that was so powerful, and it just felt like a calling.”

She took the risk to quit her job and start MemoryWell. Unlike in her work as a journalist, Newton-Small doesn’t fact-check her interview partners. “If someone tells me they were on the first manned mission to Mars, I might include this if it’s important to the person.”

Newton-Small says she has tremendous respect for caregivers who are often overworked and underpaid. “They can earn more at a chain store, so they usually do this work out of compassion,” she says. “A lot of situations can be heartbreaking. If you don’t find ways to bring empathy and joy to your work, this is not a job you’re going to stick to for very long. Being able to form these bonds vastly improves how caregiving is done.”

If Newton-Small had unlimited funds, she’d love to help what she calls “Alzheimer’s orphans,” senior folks who have no family and no friends. “So, nobody knows anything about them. They can’t really tell you about themselves anymore, and they’re probably the people you’d really need to engage the most because they are declining the quickest.” She worries that “they are the most at risk because nobody’s engaging with them. In the end, it’s about recognizing them and treating them as whole people, not as a checklist or a diagnosis.”