As soon as the National Museums Scotland curator finished her presentation on the country’s Jacobite movement, the 14 people in the sun-flooded room erupted in chatter.

One woman weighed an 18th century-style beret-like bonnet in her hands. “Heavy,” she commented, to agreement from her neighbor. Others discussed similarities between Scottish and Irish history. Chuckles arose from yet another group as they passed around reproductions of a sword and “targe,” a shield padded with animal hide. “I thought it was a dart board!” one woman laughed as it caught her eye.

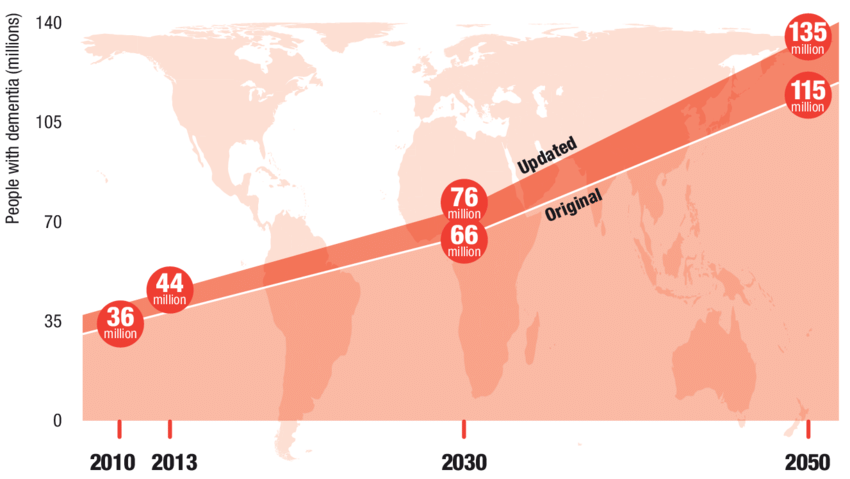

The participants were your typical museumgoers with one slight difference: they were people with dementia, their caregivers, and others who have connections to the umbrella of diseases that impact memory and cognitive abilities. Held monthly in central Edinburgh, each museum social features a different subject from the institution’s vast collection. Over squares of millionaire’s shortbread and coffee, the events bring together those whose lives are touched by dementia –– a growing population.

More and more, researchers who study dementia, which has no cure and very few treatment options, are studying whether immersion in cultural environments can be a non-pharmacological option to improve quality of life and mental health. What they’ve learned is encouraging. Opportunities to delve into history and art have been found to offer a range of benefits to people with dementia, including social engagement, cognitive stimulation and improving general feelings of well-being.

Jane Miller, National Museums Scotland community engagement manager, has organized socials on science fiction, Roman history and the history of flight. Participants have joined in quizzes, and handled ancient Egyptian charms and meteorites. For her, the socials emphasize that a dementia diagnosis need not hinder people from exploring new interests.

“It’s not just what we did in the past, or when I was a child, when I was younger, when I was supposedly more alive,” Miller says. “You’re still alive now. It’s still valuable to be learning and thinking about the future.”

Paul Camic, honorary professor of health psychology at University College London, is also interested in the potential of non-pharmacological programs, like art and culture-based initiatives.

“It’s not just focusing on the problems of dementia, or the illness aspects of it, but it’s also focusing on what can be done when you have a condition that medicine could do very little right now to alter,” he says.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York City pioneered the approach 20 years ago. While MOMA had a long history of working with people with disabilities, Francesca Rosenberg, director of access programs and initiatives in MOMA’s department of learning and engagement, says the institution hadn’t focused on dementia until a pilot with local care homes started in 2003. The program expanded in 2006 with Meet Me at MOMA, regular events open to people with dementia and their care partners.

MOMA’s format has since been adopted by other museums, Rosenberg says, adding that the dementia-focused sessions follow a similar format to programs for other audiences. Facilitators ask participants what they observe in a piece, how they interpret it and any connections they feel. They try to foster conversation between people who arrived together, and new social connections.

Over the years, friendships bloomed. Once, when two groups of Meet Me regulars arrived at the museum on a day when there wasn’t an event, Rosenberg was concerned they’d gotten the time wrong. It turned out they’d set up their own museum date.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.MOMA went on to develop guidance for other institutions to engage people with dementia in art. Today, about 140 museums worldwide have similar initiatives, according to Rosenberg. Art galleries, historic properties, botanic gardens and more built programs that suit their own collections, spaces and communities.

“These are not like replicas of what we do at MOMA,” she says. “They kind of take the idea and then run with it, which is fantastic to see.”

Rosenberg says that instead of reflecting on the past, the museum’s sessions focus on people’s abilities in the present. She remembers once asking a man in his eighties with dementia, “What did you do?” expecting him to respond about his former profession. Instead, he responded, “I’m still learning.”

“That has stayed with me ever since, that these individuals are still … open to learning, to being part of the world and part of new experiences,” Rosenberg says.

That emphasis on new learning, rather than reminiscence, is a common theme across many museum-based programs, according to Camic. Different institutions build programs around handling heritage objects, viewing artwork, or participants creating their own art.

Museum-based events combine engagement in new subject matter with social settings — a particularly important element because cognitive impairment can be very isolating, he says. Making public spaces and institutions more accessible for people with dementia is also impactful.

“It allows people with dementia not to be seen just as patients,” Camic says. “They really get to be seen as people, people participating in a usual and normal activity.”

In his research, Camic says, participants in museum programs have reported a sense of happiness, curiosity and increased confidence. The sessions are found to be cognitively stimulating. One study at a German museum, which included viewing and then creating art, found attendees experienced reductions in depressed moods, apathy and anxiety. A study in Australia that tested saliva of participants in an art museum’s dementia program found stabilized levels of cortisol — a hormone that can indicate stress. In adults generally, cultural engagement has been linked to reduced depression and anxiety, findings that Camic says also apply to people with dementia.

Research on the long-term impacts of museum-like programs on dementia has not been done, according to Camic. It’s also challenging to study, he notes, because there are many forms of dementia, and individuals’ courses of illness differ significantly.

Despite this, Elizabeta Mukaetova-Ladinska, a professor of old age psychiatry at the University of Leicester, sees many benefits of art. Activities provide structure to the day, and occupy participants with something they enjoy doing. People tend to be more focused, and wander less, she says.

“The well-being and the achievement and the pleasure out of it lasts for some time,” she says.

Wendy White noticed differences in her parents, who were both diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, on days when they attended the socials at National Museums Scotland.

Her mother could be grumpy at home, she says, but would be cheerful and more settled. Her father often made pleasant comments after museum visits, like how lucky they were to live in Edinburgh.

“He was sort of happier,” she says. “You knew he’d had a nice day out.”

National Museums Scotland’s monthly socials, and similar events at other Edinburgh cultural institutions, became fixtures on her parents’ calendar. Dementia can be a very isolating experience for individuals and carers, she says.

“Gradually, step by step, month by month, year by year, their worlds become smaller,” she says. “It’s just very hard to actually enjoy life when there is nothing to do and nowhere to go and no one to see.”

White’s father, a former engineer, was particularly engaged by topics related to science — presentations about the history of flight and clocks triggered his interest. Her mother, who died last year, loved learning about objects of great beauty, and enjoyed the chance to chat with fellow attendees. White says even just the opportunity to visit the architecturally impressive museum in the city’s historic center was stimulating.

Practical considerations like handicapped accessibility are important, she notes. For her father, who is hard of hearing, listening devices made it easier to follow along. Visual cues, like name tags and signs in big letters, help, too. Presenters who speak slowly, loudly and clearly are easier to understand. Subjects that had some relatability, like looking at domestic objects from distant past, could be particularly engaging.

As White’s father’s health declined, she says his quality of life remained high because of these types of programs, shaping his schedule and giving something to talk about.

“To actually have something in the diary that’s going to be accessible where you can do something new, different and enjoyable, and see a welcoming group of people and hopefully, learn something new or hear something new is just immensely valuable,” she says.

Back in the National Museums Scotland’s session about the Jacobites, after about an hour and a half, the group got ready to splinter. Some prepared to head home, others off to explore the museum’s galleries. But before departing, someone pulled up the lyrics to “The Skye Boat Song” — a Scottish folk classic about Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape after his Jacobite forces were defeated — and cued up the music. Miller, who organizes the events, says gatherings often involve a song, which is one of her favorite parts.

The soaring chorus swelled. Everyone, even the attendees who hadn’t spoken much, joined in.