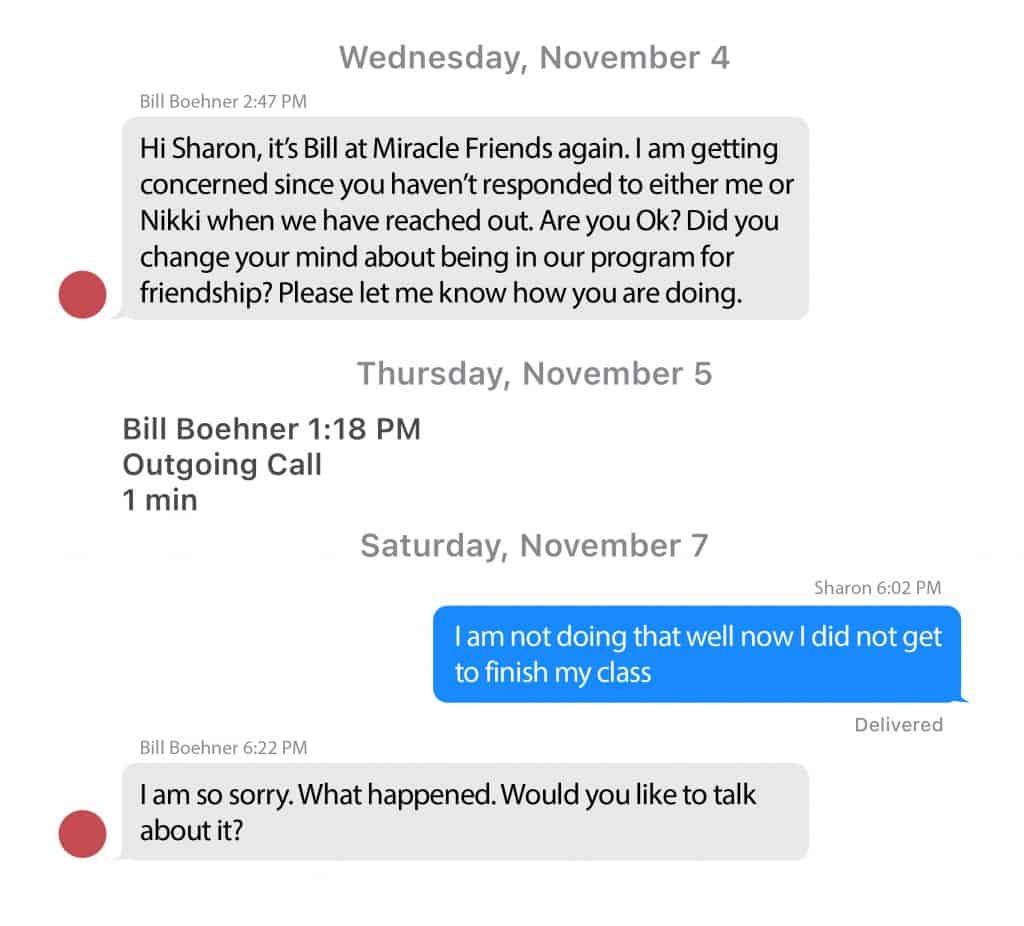

Sharon did want to talk about it. At 64, she’d taught herself to walk again after being shot on the way to work at the San Francisco airport. She’d grieved the loss of her husband to gunfire. And though she’d found relief in drugs and the streets, she was ready for change. A go-getter, she’d signed up for a course called Desk Ready so that she could work at one of the shelters she was staying at. But she didn’t know how to use Zoom or email on her phone, so she’d flunked the class.

“So I was hurting. I called Bill, and I said, ‘Bill, I’m going to get drunk,’” she recalls. “He was like, ‘Well Sharon…You the one who made the first step to decide you’re going to leave them streets alone.’”

Bill, a retired corporate accountant, also in his sixties, is a volunteer with a program called Miracle Friends. The program pairs people who are unhoused with housed volunteers in an effort to tackle what founder Kevin Adler calls “relational poverty.” For people experiencing homelessness, case managers, social workers and other service representatives abound. But what’s often missing is a stable and consistent person to rely on when the going gets rough. A growing body of research shows that relationships with peers or volunteers like Bill can help people living in precarious situations and even improve outcomes within existing programs.

Other programs like Miracle Friends exist. In San Jose, Streets Team builds peer-support networks to help folks re-enter the workforce, and in Baltimore Thread seeks to replicate the social fabric of family for youth-at-risk. And the evidence is on their side. Social support is widely known to protect against health problems like cardiovascular disease and depression. More specifically, one study, showed that 51 percent of unhoused women in Los Angeles reported no substantial source of social support. Yet those with support from someone who was not a substance user reported higher self‐esteem, greater life satisfaction and lower anxiety and depression. One analysis even found that women living in poverty with social supports had a lower risk of experiencing violence.

Adler himself believes that Miracle Friends was integral to the success of their recent universal basic income pilot, Miracle Money. Modelled off a similar program from Vancouver that RTBC reported on last year, Miracle Money gives participants $500 a month, no strings attached. “A little bit of support, walking with someone, not by someone, can lead to a transformative outcome,” he says.

‘I kept talking’

Miracle Friends got its start just as the pandemic hit, when suddenly thousands of people living on the streets of San Franciso were moved into shelter-in-place hotels, alone, and could easily slip through the cracks.

Before the pandemic, Sharon was getting tired of life on the streets and had started to turn her life around. When she first connected with Bill a year and a half ago, “I think we stayed on the phone for a couple of hours,” she recalls. “And you can say a lot talking to somebody in a couple of hours. He made me feel so comfortable… And from that day on I kept talking to him.”

Shortly after that, she flunked the course. She was also facing many other challenges — bureaucratic barriers to stable housing, racist bullying in the shelters, less-than-on-top-of-it case managers. But having Bill there as a nudge to persevere helped her stay accountable to her own goals. He’d remind her of her many accomplishments: that she was one of the best cleaners at the airport. That she cared for her sister who was disabled. That she’d always kept herself out of debt.

She hung in there. Months later, Sharon finally secured a suite in an income-assisted housing complex for seniors.

‘You’ve gotta be ready’

A couple of months after launching, Miracle Friends conducted a survey of participants. Using the UCLA Loneliness Scale, they found unhoused friends were less lonely than when they started. Forty-three percent said the program uplifts their spirits. This is important, but Miracle Friends is really about connecting people who are unhoused with a stable and emotionally supportive person. Whether the volunteer is simply listening, helping them open a bank account or serving as a reference, over time, this relationship could be the thing that indirectly helps them secure housing.

Importantly, people in the program are met exactly where they are at. They opt-in for a friend and only stay in the program if it’s benefitting them. If a participant stops responding, the volunteers do their best to find out why. In one instance, a fellow’s primary language wasn’t English so they matched him with an Urdu-speaking volunteer. But he became frustrated with the volunteer’s limited vocabulary. The volunteer asked her dad to break the ice, and the original pair have since grown to be friends.

At times, underlying mental illnesses as a result of life on the streets can get in the way, and in a few instances, pairs have required intervention due to inappropriate behaviour from the participant toward the volunteer.

According to the program, the biggest barrier remains access to phones — they’ve had to turn people away who don’t have one. But the biggest barrier as far as Sharon is concerned? “You’ve gotta be ready to want to clean your own life up.”

‘It goes both ways’

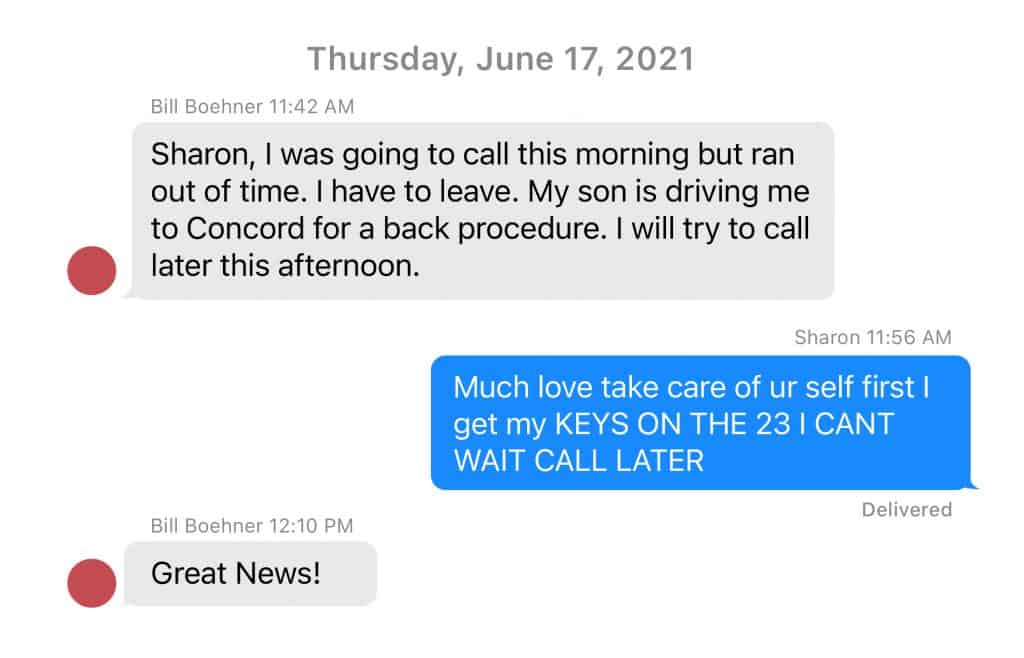

Miracle Friends volunteers can nominate unhoused friends who they think would benefit from the Miracle Money program. In December, 2020, Bill nominated Sharon. Sharon thought it was fake. Bill still titles the call he got from her after she received her first payment in May “The Happy Call.” She used the funds to get settled into her new place.

“I moved here with an air mattress and nothing else, a bunch of boxes of packed clothes,” Sharon says. “Today, I have a living room set, a dinette set and a bed, and I am very happy.” She’s returned to a healthy weight. Recently, she came full circle and was hired to work full-time at a shelter.

Having spent over a decade working with another homelessness outreach organization, Bill says the beauty in Miracle Friends is its simplicity. “You listen, you encourage. Sometimes you have to hold them accountable. It goes both ways.”

He’s clear he can’t take any credit — Sharon did it all herself. And while she’s enormously grateful to Bill, she agrees. “I came from the gutter back to reality,” she says. “I’ve done it and I’m not going to stop doing it now.”