In recent years the idea of eliminating library fines has been adopted by one city after another. As a result, people, especially low-income folks, have returned books and gone back to using their local libraries.

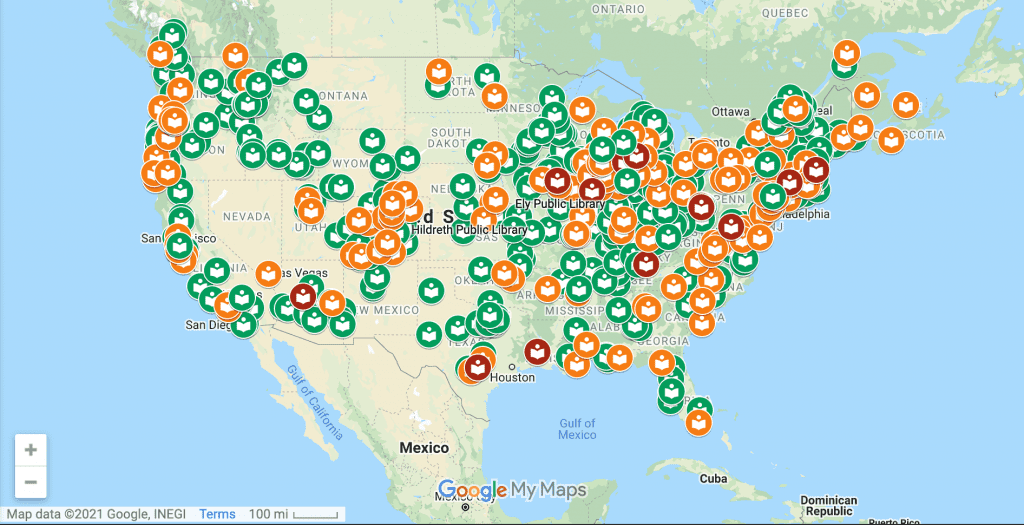

Above is an interactive map of fine-free libraries. You can access it here.

I’m not sure who initiated this idea, but it has caught on widely. Here’s a timeline of its adoption in some major cities:

- Columbus, Ohio: January 2017

- Salt Lake City: July 2017

- Baltimore: June 2018

- Denver: January 2019

- Cleveland: July 2019

- San Francisco: September 2019

- Chicago: October 2019

- Phoenix: November 2019

- Philadelphia: February 2020

- Los Angeles: Spring 2020

- London: November 2020

I’m sure I have left out a lot of cities and towns — clearly the idea is a snowball that has gained momentum. But does it work? And does it have any negative consequences? Here are the questions that typically come up.

Why eliminate library fines?

As with lots of fines, overdue book fines discriminate based on income. For instance, in New York, of children and teens with blocked public library memberships, nearly half came from branches in “high-needs” neighborhoods. (In response, the New York Public Library wiped clean all fines for kids and teens in 2017, but it still charges fees for overdue materials.)

This suggests that folks for whom a fine is a financial burden often simply stop using the library, while wealthier folks can just return their late books and pay the penalty. Since income in the U.S. often correlates with race, this leads to a lot of BIPOC kids losing access to books, computers or even a quiet space they need to improve their situation.

So fines are as much a social justice issue as a simple economic one. Library use fosters reading, and reading and literacy leads to better health outcomes. It’s a win-win for the whole community.

And sure enough, eliminating fines works. When fines aren’t in the way, folks return their overdue books and begin using their libraries again. For instance, when the San Francisco Public Library held a six-week fine amnesty period, some 700,000 items were returned — including a book that had been taken out a century earlier — and 5,000 patrons had their memberships restored.

Aren’t fines a source of income for libraries?

They are, but for many libraries it’s a tiny percentage of their budget. In Baltimore, which got rid of fines in 2018, it was less than one-quarter of one percent of the library’s operating budget. In other cities like Denver, it’s likewise less than one percent. Can they survive without it? Yes — but there’s a sort of humorous twist here: In some cases, the money brought in from fines was often used to track and process those same fines. Eliminating the fines is therefore often a wash.

Aren’t fines an incentive for people to return their items?

It turns out, for the most part, they are not. In the ‘80s the Philadelphia library doubled its fines in the hopes of getting more books returned on time. It had zero effect on return rates but overall borrowing went down.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.In fact, studies have shown that fines have almost no effect on the timely return of books — the stick does not always encourage good behavior. Fines not only don’t encourage borrowers to return books, they act as a barrier that deters folks — especially low-income folks — from using the libraries at all.

Won’t folks just steal books if there are no fines?

Siobhan Reardon, president of the Philadelphia Free Library, which eliminated fines last year, told WHYY that hasn’t been the case. Since you typically can’t check out more books until you return the ones you have, the potential for theft or hoarding is very limited.

How did this wave of policy changes happen so quickly?

In many places it was more gradual than it appears. Eliminating ALL fines makes the news, but many libraries were already chipping away at them incrementally. Cleveland eliminated fines for seniors way back in 1977, for children the following year, for disabled folks in 1992 and for teens in 2001. So for some libraries eliminating all fines was simply the final step in a long process during which they could monitor the effects along the way.

What are the effects?

A number of library systems have seen patronage rise as overdue books are returned and outstanding fines are forgiven. In Chicago, for instance, the number of returned overdue books jumped from 900 a month to 1,650, and 11,000 of the folks returning them renewed or replaced their library cards. Now, more books in Chicago are being checked out overall — circulation has increased by seven percent from before fines were cut.

The pandemic put a serious dent in that trend, as libraries had to close, but now folks are checking out more e-books instead. If e-books are the future, we may soon see a day when library fines cease to exist altogether, since you don’t return an e-book to the library — it simply vanishes from your device when the borrowing period expires.

Cleveland Public Library Executive Director Felton Thomas Jr. explained the movement to eliminate fines in a quote I think sums it up nicely: “We want to remove barriers, not block people from accessing the library. We want to connect people to knowledge and ideas, not stand in the way. This important step will help us do our everyday work of fostering learning experiences — sparking curiosity, making connections, and building skills every day for all Greater Clevelanders.”