We had planned to call this “The Year in Cheer” because… well, because it rhymes. But then we started looking at the last 10 years and realized how much had changed. Issues that were hardly on the radar a decade ago, like transgender rights, began earning the attention they deserved. Meanwhile, problems from the past, like damage to the ozone layer, turned a corner. A decade that often seemed to be mired in muck actually boasted major progress. But don’t take our word for it—read our list of how things have gotten better since the dawn of last decade.

The developed world used less water, despite population growth

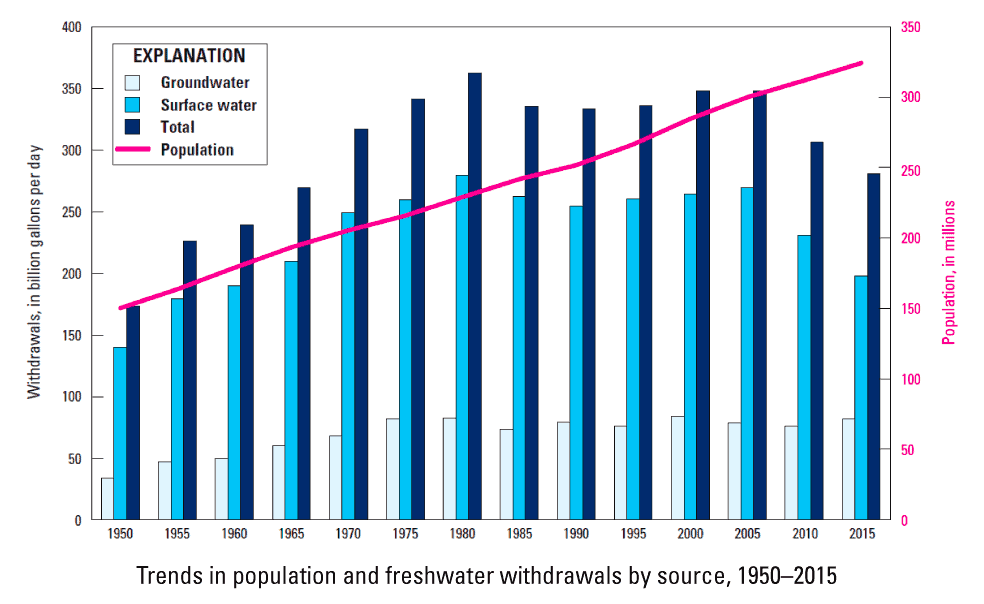

In 2015, the last time water use was measured nationally in the United States, the country used less water than it did in 1970. Despite more than 50 percent population growth and massive increases in agriculture and industry, the United States is consuming less water than it was nearly 50 years ago.

In an era of intensifying drought and water shortage, this news is as welcome as it is surprising. It does not necessarily mean that more of us are turning off the water while we brush our teeth, however — the decrease is attributed primarily to lower water consumption for thermoelectric power and agricultural irrigation. According to a report by the U.S. Geological Survey, this is proof that “water conservation efforts and greater efficiencies in using water have had a positive effect.” Water use peaked in 1980 and flatlined for several years until 2010, when usage began dropping dramatically.

And it’s not just the United States. Water use in Canada dropped 12 percent between 2011 and 2017, and academic reports have showed reduced consumption in major cities across Europe from Sweden to Italy and Spain, all primarily attributed to the same: industry and agriculture. In short: your low-flow toilet is awesome, but water-free farming is the future.

The (whole) world became less transphobic than it once was

Read any chronological list of victories for LGBT rights, and you’ll notice a trend: the word “trans” barely makes an appearance until you hit the 2010s. That’s not to say the victories didn’t exist — trans and non-binary rights activists made incredible strides before the decade hit. But it’s almost as though it wasn’t until the 2010s that LGB rights had come far enough that T rights could really start to share the spotlight.

It was the decade that six-year-old Coy Mathis won the right to use the girls’ bathroom at school, and that gender-inclusive restrooms became the norm in many public buildings and workplaces. In 2014, the Swedish Academy Glossary officially inducted the gender-neutral pronoun “hen” into the Swedish language, and in 2019 the English gender-neutral pronoun “they” became the Merriam-Webster Word of the Year.

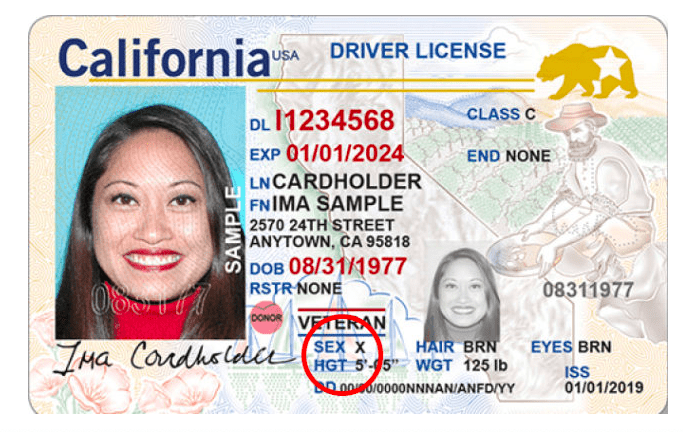

But the biggest changes were institutional, and they come down to one word: recognition. Some might be expected: California and Oregon began allowing a non-binary “X” (in place of “F” or “M”) on birth certificates and state-issued IDs, and Canada allowed the same on passports. Perhaps less expected was the Botswana High Court’s recognition of a trans woman’s gender, or Nepal’s legal recognition of a third gender. Vietnam’s National Assembly paved the way for the legal recognition of trans people, and even Hong Kong and the Philippines showed an openness to learning about what legal gender recognition might look like for them.

The 2010s was also the decade that the WHO finally decided being transgender isn’t a mental illness.

These institutional shifts reflect a more personal reality: the vast majority of people these days are less transphobic than often assumed. “Globally, nations’ media outlets tend to pander to the perceived prejudices of its audiences,” reported the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (IGLA) in 2016. But, the report found, “With exceptions, on most of the questions asked in the 2016 survey, public attitudes in both hostile and friendly nations are not as extremely negative as might have been feared.”

Overwhelmingly, in fact, the majority of people in the world (67 percent), including in places like Saudi Arabia and Algeria, feel that human rights should extend equally to trans people. “Of significant note, the survey reveals that only 17 percent of the world (somewhat or strongly) disagrees with the proposition, and feel that human rights should not be equally applied to all.”

The trans rights movement still has so many battles to fight. But for a brief moment, let’s appreciate the victories… and then get back to work.

The ozone layer started healing

Remember when we worried about the ozone layer? That fleeting era when we stopped using aerosol hairspray until the industry got its $&%# together and stopped putting CFCs in it? Well, it worked. In 2005, almost 20 years after the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, we got the first proof that ozone layer depletion was slowing. But it was 2018 when the UN gave us the news we’d been waiting for: the ozone layer actually healing. At projected rates, the holes we blew in the earth’s natural sunscreen are scheduled to heal completely by 2030 in the northern hemisphere and mid-latitudes, by 2050 in the southern hemisphere and by 2060 at the poles.

The news of the ozone layer healing is a little fraught. A lot of the CFCs that caused the depletion were replaced by fuels that emit greenhouse gases, for example. But the Montreal Protocol was an incredible example of coordinated global action to tackle a major, worldwide environmental problem — possibly the first of its kind. And while it was easier than tackling climate change (the primary emitters of CFCs found substitutes with little disruption to their industry), it’s a reminder that we actually can work together to reverse the havoc we’ve wreaked on the atmosphere.

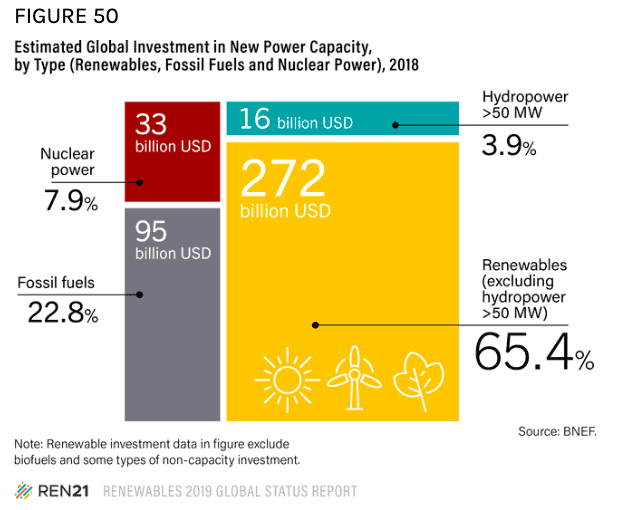

Investment in green energy far, far exceeded investment in fossil fuels

More than two thirds of all the money in the world being invested in energy is now going to renewables. If you count nuclear, that number jumps to more than three quarters. That’s right — 77 percent of the billions and billions of dollars invested in energy today is going to something other than fossil fuels.

It was only 2010 when the scales first tipped and the world spent $187 billion on wind, solar, tidal and biomass production, over only $157 billion on fossil fuels. Since then, renewables have skyrocketed, raking in $288 billion ($321 billion if you include nuclear) in 2018 over the meager $95 billion fossil fuels cobbled together.

On top of that, about a thousand major investors have divested from fossil fuels since 2011, meaning they’ve pulled out of the stocks and bonds they had invested in fossil fuel companies. And while those divested dollars haven’t always gone to support renewables, together they equal between six and eight trillion dollars worth of power taken out of the hands of fossil fuel companies.

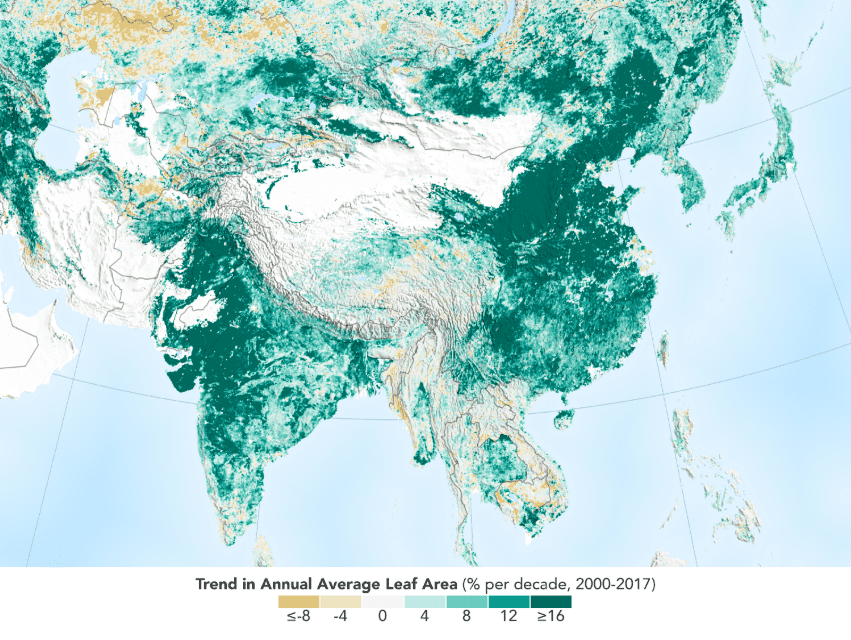

The world got greener

Not only did it get greener, we made it greener. That’s right, counter to every narrative we might hear, humans have made the world a greener place over the past decade.

To be fair, the world has been getting greener for some time now. NASA scientists first noted the phenomenon in the mid 1990s, but didn’t have the data to put their fingers on how it was happening. Now, a couple decades later, the results are in: the world has gained two million acres of leafy cover per year, an increase of about five percent since 2000, equivalent to the leaf area of all the Amazon rainforests. The primary source of the new foliage? India and China — “a surprising finding, considering the general notion of land degradation in populous countries from overexploitation,” according Chi Chen, lead author of the study.

According to NASA, China’s “outsized contribution to the global greening trend” can be attributed primarily to aggressive forest conservation and expansion projects designed to mitigate local soil erosion and air pollution, as well as climate change. Meanwhile, 82 percent of the greening in India (and 32 percent in China) is a result of food crop cultivation. Interestingly, the land area used to grow crops has remained constant (about 770,000 square miles) in the two countries over the past 20 years. Instead, the increase in yearly green is the result of greater crop rotation throughout the year.

While researchers note that this news doesn’t make up for the devastation of, say, the Amazon rainforests, study co-author Rama Nemani sees hope in the findings.

“Once people realize there’s a problem, they tend to fix it,” he said. “In the ‘70s and ‘80s in India and China, the situation around vegetation loss wasn’t good; in the ‘90s, people realized it; and today things have improved. Humans are incredibly resilient. That’s what we see in the satellite data.”

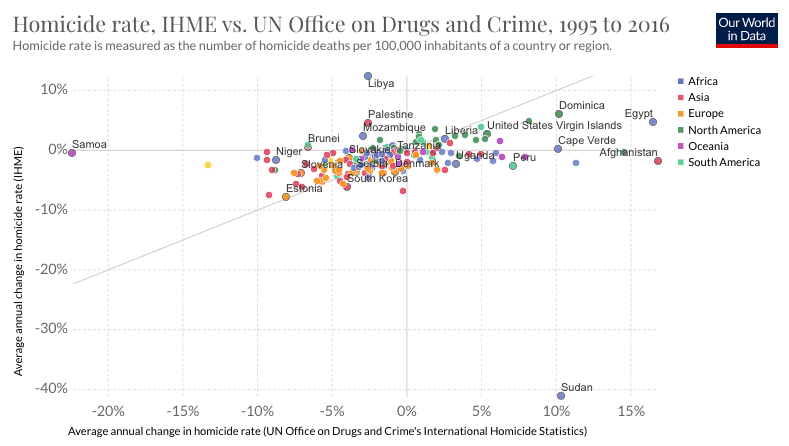

Homicide rates fell worldwide

Despite what the true crime boom would have you believe, homicide rates are scraping record lows across the world.

Every global region other than Latin America saw a drop in murder rates between 1990 and 2015, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Declines in North America and Western Europe were especially precipitous — in a 25 year period, homicides in both places fell by 46 percent. The effect has been felt most strongly in large cities, which are home to most violent crime. New York is experiencing fewer murders today than any time since the 1950s. In Glasgow, dubbed the “murder capital of Europe” 15 years ago, homicides have fallen by 60 percent. Even countries like Australia and Sweden that never had high murder rates have seen significant drops. What’s going on?

There are lots of theories, from people carrying around less cash to technology keeping more people in the house. But one of the most compelling explanations is that the world is getting older. Most violent crime is committed by young people (particularly young men), and older societies tend to be more orderly places. The online magazine Mic crunched the data and found that in the safest countries, a one percent increase in young people corresponded with a 4.6 percent rise in murder rates. (Japan, one of the world’s oldest nations, is also one of the safest.) Older people may pose certain challenges to society, but rarely do they kill people. (And when they do, it makes the news.)

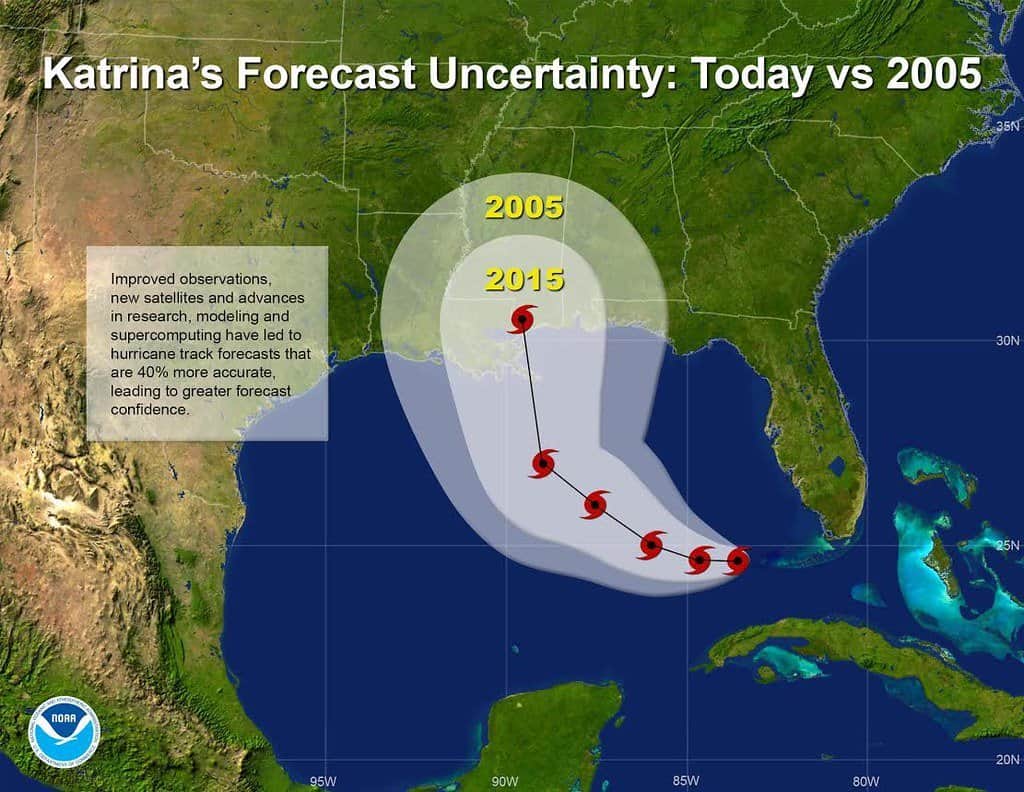

Weather forecasting became a lot more accurate

Weather forecasts “have advanced light years” over the past decade, saving not just holiday weekends at the beach, but thousands upon thousands of lives.

Of course, it’s not as if weather forecasting wasn’t getting better before this decade. Six-day forecasts in 2015 were as good as three-day forecasts in 1975. But the past ten years have seen a big jump in precision. When Hurricane Katrina struck the U.S. in 2005, scientists had the ability to issue cyclone warnings an average of 24 hours before landfall. By 2015, that lead time had increased to 36 hours — a 50 percent leap, and an extra 12 hours to run for the hills.

Today’s forecasting techniques make yesterday’s look like reading tea leaves. For instance, in the ‘90s, meteorologists measured hurricane intensity by comparing satellite pictures to storms from the past. The difference today, as the Washington Post recently put it, is “like comparing television resolution in 1960 to the 4k-flat screens.” Supercomputers, a greater number of weather satellites orbiting the earth and more dynamic data measurement techniques have changed everything, cutting one-day hurricane track errors down to half of what they were back then. So if you get caught in a downpour, you’ve only yourself to blame.

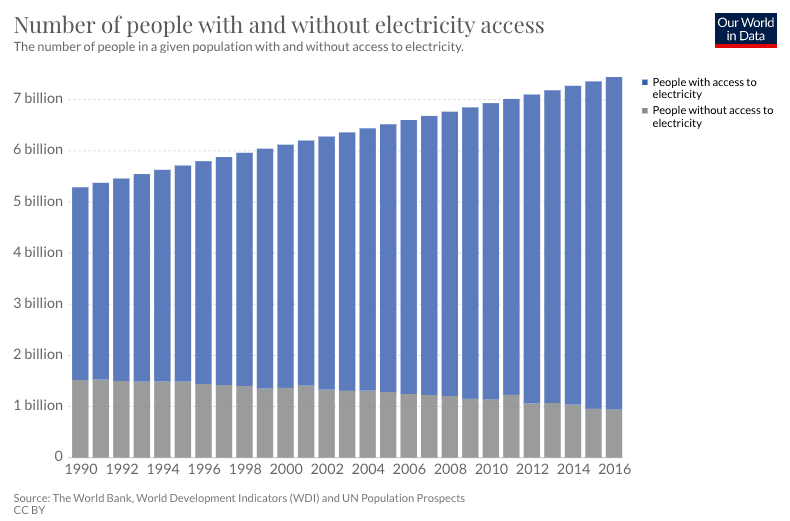

The number of people without electricity fell below one billion

In Bangladesh, one out of five people had electricity in the year 2000. Today, 93 percent do, including those living in the most remote villages. Bangladesh reflects a worldwide trend: countries that were dark and quiet 20 years ago now hum with hospitals, factories and refrigerators. Life in those places will never be the same.

The electrification of the world is one of this decade’s quieter global phenomena. In 2010, 1.2 billion people had no electricity. By 2016, that number had fallen to billion. Today, it’s 840 million. In a single year in 2017, over 120 million people gained access to electricity for the first time. In 2018, India, soon to be the world’s largest country, electrified all of its villages. Kenya went from 32 percent electrified just five years ago to 75 percent today.

Electrification has drawbacks. Depending on the power source, it adds emissions to the atmosphere. And some researchers have questioned whether electrification even accomplishes its primary goal: lifting people out of poverty. The upside to getting electricity at this late stage is that, done right, it can leapfrog fossil fuels entirely — in Kenya, an amazing 90 percent of the energy produced is renewable.

Universal health care went from privileged ideal to global ambition

Efforts to make sure everyone can see a doctor began centuries ago, but the past decade saw a major global shift toward universal health care. The progress came not from the developed world, where most countries have had UHC since the 1970s, but from a wave of developing countries that moved toward universal access in the new millennium.

Few have actually managed to cover everyone — that’s a very long-term goal, which is why the World Bank gives much greater weight to efforts to expand coverage dramatically. By that measure, the gains have been enormous. According to a 2015 report, dozens of countries have made “significant strides toward UHC with a focus on the poor and vulnerable.” It was only in the past decade or so that the world’s biggest middle-income countries — China, India, and Indonesia, for example — made major reforms aimed at achieving UHC. Their efforts gave health coverage to 1.5 billion new people, and “over half the programs have more than doubled their coverage rate over this short time.”

Perhaps most heartening, until recently, many UHC programs failed to reach the poorest. The newest programs, however, are much more oriented toward marginalized people. The World Bank describes them as “at once new, massive, and transformational: new because they have mostly been launched since the turn of the century; massive because they cover almost 2.5 billion people (and counting), or about one-third of the global population; and transformational in that they do not just expand coverage but fundamentally change the way that broader health systems work.”

And that’s not all…

From same-sex marriage in Taiwan to the booming fake-meat market, this decade produced countless examples of progress. Here are just a few more: