Fishing boats on the quay gently rock in the waves of the North Sea. They send their catch to processing plants by the wharf, where refrigerated trucks await out front. Commercial fishing dominates the port of Hirtshals on the Skagerrak strait in northern Denmark. Just a few hundred meters away, however, an innovative company is challenging this centuries-old industry.

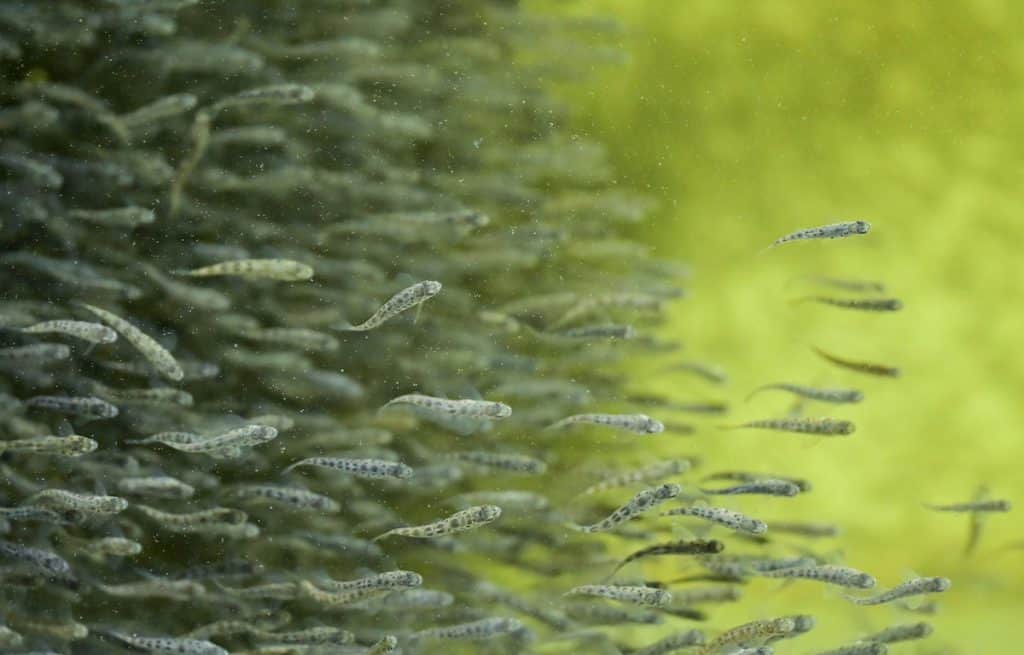

In a closed-loop system, Danish Salmon is raising salmon not in the sea, but on the land. “We check the fish every day,” says the company’s production manager Arndt von Danwitz, flicking on his headlamp. With slight movements of his head, he illuminates perforated aluminum boxes that stand in a long basin through which cold water flows. It’s cold in the room, too — about as cold as the air where you might find a Nordic mountain stream in winter, to “mimic nature as much as possible,” says von Danwitz. In this frigid water, about 15 millimeters long and very thin, are the fish. They hatched just three weeks ago, and won’t be mature enough to harvest for another two years. “Salmon farming is for patient people,” he smiles.

For those who do have the patience, the rewards are substantial. The world is eating more salmon than ever. In 2021 alone, consumption increased by 13 percent. The EU and UK were the largest markets, consuming 1.28 million tons. In the US, the appetite for salmon is also high — Americans ate some 634,000 metric tons of it in 2021.

Only one-fifth of all this salmon — over five million tons — comes from wild stocks. The rest is farmed, most of it in open net cages off the coasts of Norway, Chile and Great Britain. Scotland, Canada, Iceland, Russia and the US also farm salmon this way. But the method has consequences, often involving mass quantities of medicines, pollution, rampant pest infestation, high mortality, and the endangerment of wild stocks.

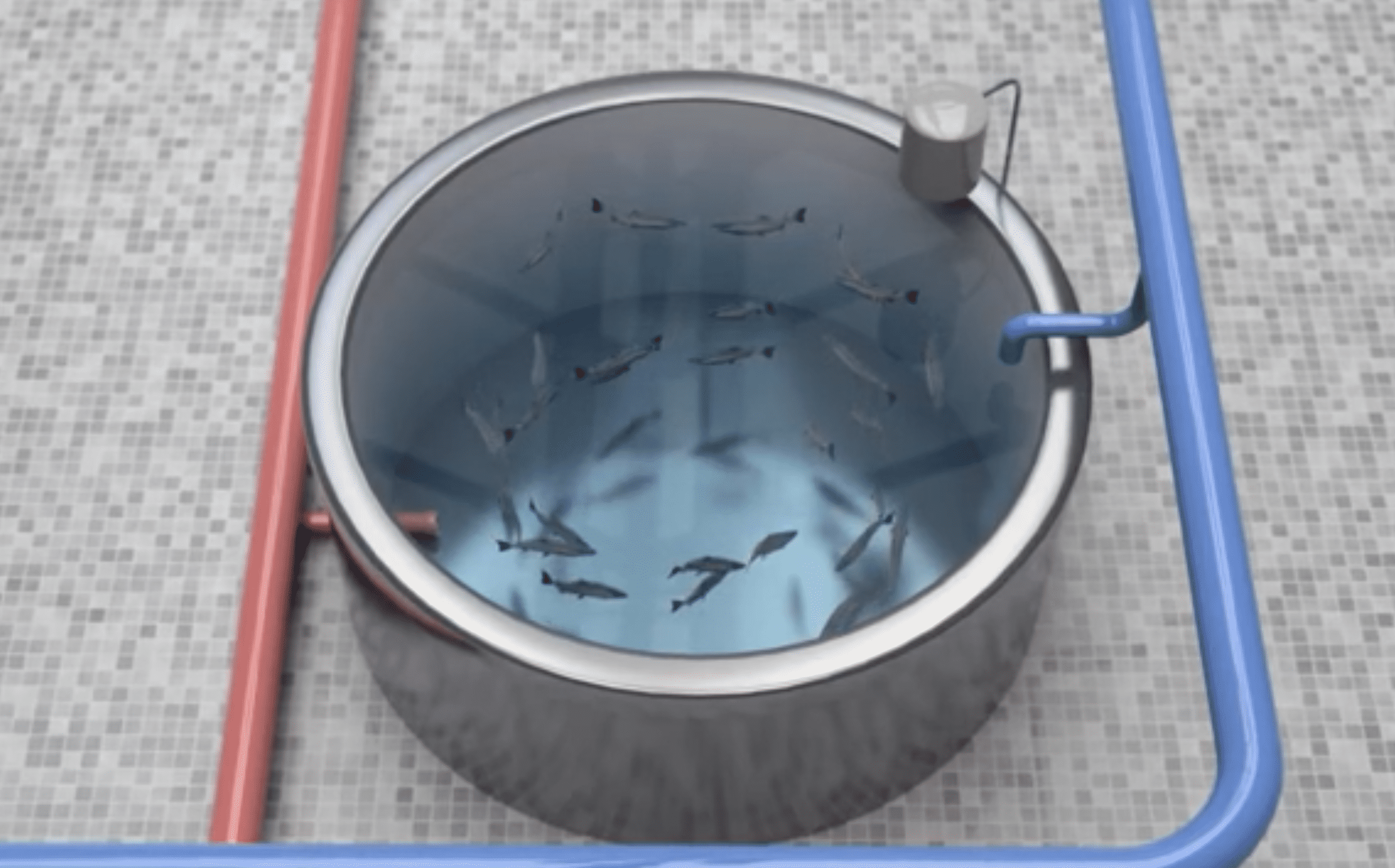

Danish Salmon, on the other hand, raises its fish in a closed water network that is pumped through biological purification systems every 40 minutes. A drum separates fecal matter and feed residues, which are sent to a nearby biogas plant and turned into green electricity, renewable natural gas and fertilizer. Bacteria break down the dissolved substances in the water of the breeding tanks, such as urine and ammonium. In addition, the plant enriches the water with oxygen.

“We thus remove 80 percent of the phosphorus and nitrogen from the water before pumping it back into the sea,” says von Danwitz — two substances that cause oceanic dead zones, and are produced in abundance by fish farms.

The seawater that streams through Danish Salmon’s breeding facility comes from the Skaggerak, a heavily trafficked strait of fishing and cargo ships between Denmark and Norway. The water is biofiltered with sand, then treated with ultraviolet light, which prevents a parasite called salmon louse, which bites through fish skin to cause open wounds. Salmon louse can spread rapidly through dense populations of farmed fish, and outbreaks often controlled with insecticides, bleach and disinfectants. With no chemicals whatsoever, Danish Salmon has been producing parasite-free salmon for nine years. Nevertheless, a veterinarian checks in every month as required for the ASC seal for sustainable aquaculture.

Danish Salmon also eschews artificial pigments to color its salmon, and its closed system eliminates the need for antibiotics. “The use of antibiotics alone is prohibited by our bacterial culture for water purification, which has been built up over a long period of time,” says von Danwitz. And needless to say, salmon farmed on land can’t escape into the wild. This is a real problem. Norway reports an average of 450,000 escapes from its fish farms each year, and many more desertions go unreported. These fugitive fish mate with wild salmon, changing the gene pool.

Currently, 850,000 salmon ranging from one one-hundredth of an ounce to nearly nine pounds live in Danish Salmon’s tanks. As of August, that number is expected to increase significantly. Next door, heavy machinery is adding capacity that will allow the company to produce two-and-a-half times as many fish. At present, however, even 1,100 tons of salmon per year is far less than the average 8,000 tons produced in a single open farm in Norway (several hundred of which exist). The cost of sustainable salmon is also about one-third higher than the conventionally farmed product. Nevertheless, demand for it — from caterers to supermarkets — always exceeds supply.

Though land-based salmon farming is rare, with a global production volume of roughly 10,000 tons, it is growing very quickly — by 30 percent in the past year. Not far from Danish Salmon, a new facility has just started production. In Florida, Atlantic Sapphire plans to produce 220,000 tons annually by 2031 in a closed-loop system. Even high in the Swiss Alps, salmon swims on land. Most of these farms are built where fresh salmon is consumed, depriving the fish of the wasteful habit of flying. (Shipping salmon from Norway to the four most important Asian export countries results in 5.3 to 6.3 kilograms of CO2 emissions per kilogram of fish.)

But land-based salmon farming is resource intensive, too. Danish Salmon’s electricity bill includes seven to eight million kilowatt hours each year, mostly for cooling and pumping. The company gets this power from renewable sources, mainly wind. In Danish Salmon’s new building, production is already expected to consume one-third less energy. In the next few years, the operators aim to save an additional 20 percent.

Danish Salmon’s CEO Kim Hieronymus Lyhne expects steep growth in onshore closed aquaculture. “It’s really just taking off,” he says. That’s also the assessment of the Japanese investors who recently financed Danish Salmon’s expansion. “Land-based, closed-loop systems are seen as having great potential; they offer some advantages over open systems, and not just for salmon,” says Fabian Schäfer, an aquaculture expert at Germany’s Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries. Some policymakers are also pushing the technology. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau wants to move all farmed salmon production in British Columbia from the sea to the land by 2025.

Already, more than half of the fish consumed worldwide comes from aquaculture. For global fish stocks to survive, that share will likely have to grow even more. More than one third of the world’s fish stocks are overfished, and the other two-thirds are largely at the limit of what they can produce. A more sustainable future for the world’s salmon may be one in which fishing boats no longer bob picturesquely on the waves of the Danish Hirtshals.