This article was originally published and generously offered to us by our friends at The Narwhal. Read the original here.

Every summer, biologist Daniel Schindler walks hundreds of kilometers up and down the Wood River in Alaska, counting red and green sockeye salmon homing to spawning grounds from Bristol Bay. Last year, the sockeye kept coming. And coming.

Schindler, a Canadian who teaches at the University of Washington, remembers thinking, “Wow, this thing is going to be bigger than we expected.” Salmon were spilling over the banks of small creeks. Streams and rivers turned crimson as fish jammed together, fin to fin. In places, the volume of fish seemed to be greater than the volume of water. “Fish just kept pouring in,” says Schindler, a professor in the school of aquatic and fisheries sciences.

By early September, almost 69 million sockeye had passed through Bristol Bay en route to the watershed’s six major river basins, where they had hatched an average of four years earlier in tiny sheltered nurseries under gravel in streams and creeks. It was the largest sockeye run in Bristol Bay since tracking began in 1893.

“Our forecast for this year was certainly strong,” Schindler, whose research focuses on Bristol Bay salmon, says. “It was going to be a good run. But it exceeded our forecast by at least 10 million fish.” Even more surprising and interesting for Schindler are the consistent record, and near-record, Bristol Bay sockeye returns over the past eight years. The previous record was broken three years ago, when almost 63 million sockeye swam back to the bay before thrashing upstream to spawn.

Meanwhile British Columbia, the Canadian province directly bordering Alaska on the coast, where wild salmon stocks are declining at unprecedented rates, can only dream of such abundance. In June, Bernadette Jordan, then minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, announced the closure of almost 60 percent of B.C.’s commercial salmon fisheries for the 2021 season, saying “we are pulling the emergency brake to give these salmon populations the best chance at survival.” With fewer and fewer salmon returning every year — “disappearing before our eyes,” in Jordan’s words — there was little choice, despite the harsh economic impact on harvesters, including First Nations businesses.

The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) says it has “serious concerns” about sockeye runs in the Fraser — the longest river in British Columbia — which experienced historically low returns in 2019 and 2020. In 2020, only 293,000 sockeye arrived to spawn — a faint shadow of the 20 to 40 million sockeye that splashed in the Fraser River one century ago. On B.C.’s central coast, not far from Alaska, sockeye populations have experienced a 90 percent decline over the past 70 years, according to research by the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance.

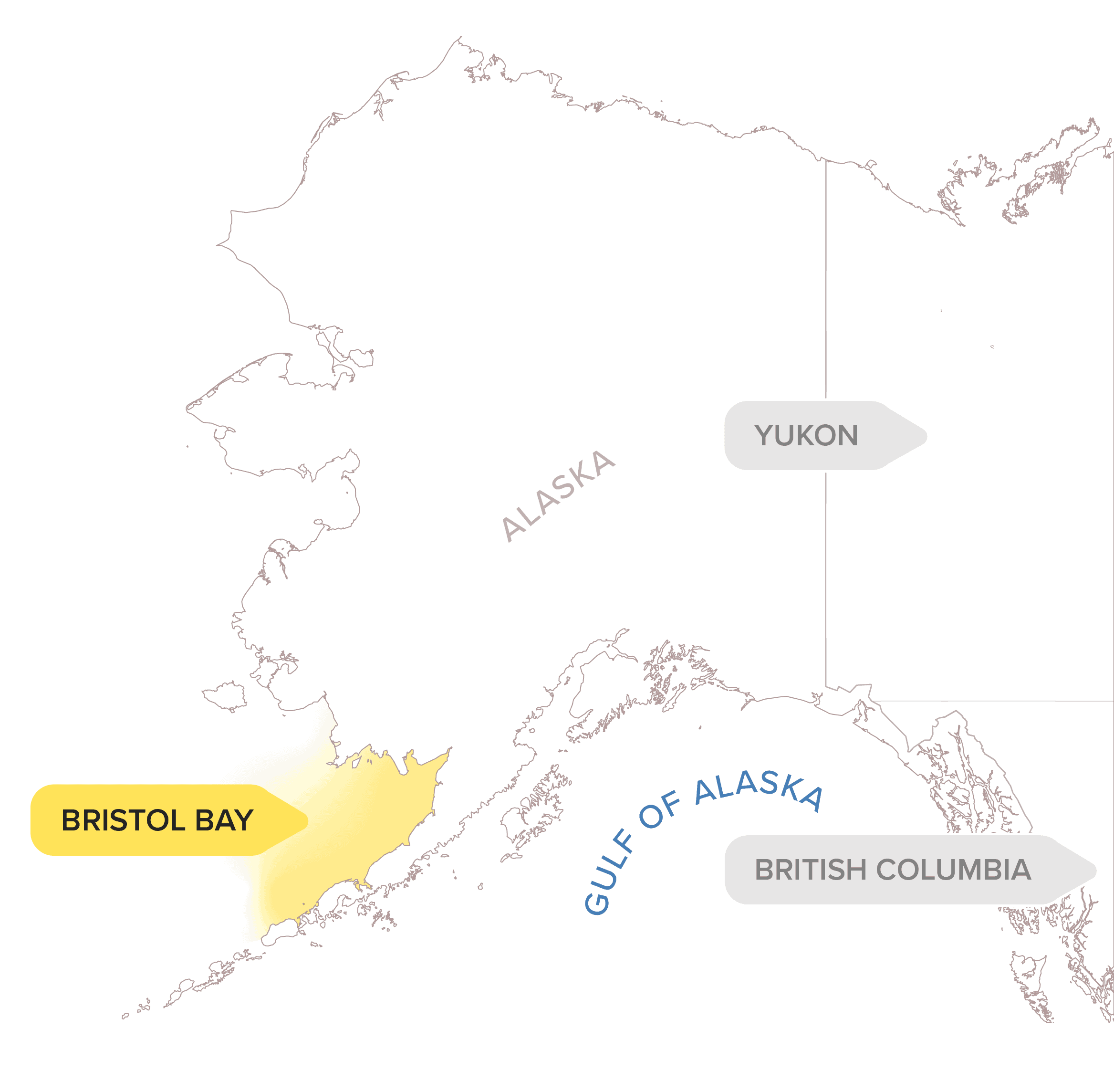

Type in ‘Bristol Bay’ on Google Earth and the globe swivels to the easternmost arm of the blue Bering Sea. Bristol Bay sits just north of the Alaska Peninsula, which drops into the ocean like a tail, eventually cleaving into the volcano-capped Aleutian Islands. The bay is known as “America’s fish basket.” Along with the world’s most abundant sockeye fishery, it’s also home to smaller runs of chinook, coho, chum and pink salmon.

Alannah Hurley, executive director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay, a consortium working to protect the traditional Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Alutiiq ways of life in southwest Alaska, calls Bristol Bay a “salmon powerhouse.”

United Tribes of Bristol Bay, representing 15 federally recognized Tribes, is determined to keep things that way. For more than a decade, along with commercial and sports fishery businesses and conservation groups, the Tribes have been trying to stop a proposed open-pit gold and copper mine that would destroy 445 hectares of wetlands, lakes and ponds and eight kilometers of salmon streams in the Bristol Bay watershed. “It would devastate our watershed and our fishery,” Hurley says.

The Pebble mine is owned by the Northern Dynasty Partnership, a Canadian subsidiary of Northern Dynasty Minerals. The mine poses what Hurley and many others call an unacceptable risk to salmon and the wealth of other wildlife that depend on the watershed, including 24 non-salmon fish species, 190 bird species, more than 40 terrestrial animals such as grizzly bear and caribou and other aquatic species, including Pacific walrus, north Pacific right whale and beluga whale.

“Our people have been able to steward this place for thousands of years, to protect our pristine watersheds,” says Hurley, who last summer caught hundreds of Bristol Bay chinook, sockeye and coho salmon to freeze, smoke and gift to Elders and other community members.

The Wood River, which flows from the icy waters of Lake Aleknagik and braids south into Bristol Bay, supported one to two million salmon in the 1970s and 1980s. “It could have easily been written off as unimportant,” according to Schindler. Now, the river churns with 10 to 20 million salmon each year.

Conversely, the Kvichak River was the biggest sockeye river in the world, by a long stretch, for most of the 20th century. “And then it went away to almost nothing,” Schindler says. “They had to close fisheries on it for 10 years. The habitat hadn’t changed through any human impacts. The fisheries hadn’t changed. Something about that population just wasn’t working very well.”

But the region’s fishery didn’t collapse; salmon populations in other rivers surged as Kvichak River populations waned.

Salmon strongholds refer to regions, not individual rivers, Schindler points out. Divergent habitats throughout regions allow for different responses to the dice roll of Mother Nature. “There’s a lot of randomness in the world, and what we’ve learned from Bristol Bay is that the region is sustainable because all the ups and downs aren’t coordinated.”

Schindler has a message for B.C. and other Pacific Northwest jurisdictions experiencing long-term salmon declines and runs on the verge of collapse: “Just because the habitat doesn’t have fish in it now doesn’t mean it’s not holding the potential for fish in the future.”

That’s a reassuring thought for Bob Chamberlin, chair of the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance, which advocates for wild salmon and encourages restoration efforts in salmon-bearing watersheds damaged by industrial development such as logging, mining and dam-building.

Those watersheds include the Fraser, where mines discharge tailings effluent, and the Similkameen, another B.C. river home to more than 50 abandoned mines. Recently, the active Copper Mountain mine leaked contaminated water into the Similkameen, which flows south across the border into critical habitat for steelhead and salmon, including endangered chinook salmon populations.

Chamberlin, who calls the state of B.C. salmon “beyond critical,” says the federal and B.C. governments need to sink far more resources into restoration efforts — billions of dollars — in a “once in a lifetime investment” to bring back salmon runs. Some Indigenous communities have lacked salmon for food, social and ceremonial purposes for years, even though they have a constitutional right to access fish, Chamberlin points out.

“When we think about what really needs to be done for B.C. salmon, we need multi-decade resourcing. We can’t just go out there and do a couple of years of work and think it’s going to be enough. With diverse salmon runs across B.C. there’re a lot of watersheds that need to be restored so they can receive salmon.”

Government funding for the B.C. Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund is just a “spit in the bucket,” Chamberlin says. The entire wild salmon industry in the province employs about 6,600 people, compared with 14,800 people directly employed in Bristol Bay’s salmon industry, which is valued at USD$2 billion. According to the consumer group Wild BC Salmon, the wild salmon industry is valued at $150 to $250 million annually, a wide fluctuation due to dominant salmon years.

Tim Bristol, executive director of Salmon State, an Alaska-based group advocating for science-based decision making and precautionary management, eagerly anticipates the annual return of the Bristol Bay sockeye. “It’s a miracle that you get to witness it year in and year out,” he says. “It does kind of leave you a little bit concerned or shaken when you think that — [although] maybe not quite at the scale of Bristol Bay — this happened all along the west coast of North America. There are so few places that are still seeing that. And that’s sobering.”

Aaron Hill, executive director of the Watershed Watch Salmon Society, a science-based non-profit group that defends B.C.’s wild salmon and their habitats, points to B.C.’s controversial salmon farms as one reason for the precipitous decline of wild salmon in the province. “They don’t have salmon farms in Alaska, so the diseases and parasites from salmon farms that B.C.-bound fish are exposed to [are] not an issue for Bristol Bay sockeye.”

Bristol Bay also doesn’t have salmon hatcheries, which are common in B.C., where DFO operates about two dozen facilities to enhance salmon stocks. Hatchery salmon pose a number of risks to wild salmon, Hill says, such as reducing the genetic fitness of the wild populations and competing for limited food.

Bristol Bay’s prolific salmon runs are also made possible because of the effective and transparent management of the Alaskan salmon fishery, according to both Hill and Schindler. Decisions are made in real time, on the ground — or, to be precise, overlooking the water — compared to the much more cumbersome and bureaucratic Canadian system.

Bristol Bay’s sockeye fisheries are managed around an escapement goal — the number of salmon in a particular stock that must escape the fishery to spawn and achieve a maximum yield — set on a river-by-river basis. Individual managers have complete authority to shut down a fishery as the fish arrive if the escapement goal is not being achieved. The fishing industry might grumble, Schindler says, but people know how the rules work and accept them. The management system is set up to be as responsive as possible, with a rapid transfer of information. Data is accumulated and made public.

“These are managers who are out in the rivers, they’re in the districts, they’re talking to the fishers every day,” Schindler says.

Hill says Bristol Bay sockeye populations have been managed to maintain the full diversity of stocks, a practice he likens to maintaining a diverse financial portfolio, “so there’s always something coming back strong.” If one population is returning at a lower abundance than others, fishery managers don’t allow it to be overfished with the stronger populations.

“That’s something we’ve been very bad at in B.C.,” Hill says. “For the most part, we allow weaker populations to be overfished in order to get at the stronger populations that are swimming alongside.”

For Chamberlin, the path to healthier B.C. salmon stocks starts with allowing First Nations greater involvement in decision-making. Such involvement would also move beyond the “lip service of consultation” and represent a significant step towards reconciliation, he believes.

Embracing substantive shared decision authority with First Nations when it comes to watershed management and salmon runs would benefit both the environment and British Columbians, Chamberlin says. He’s deeply involved in a First Nations salmon restoration framework for B.C., which includes First Nations all over the province who are determined to recover salmon runs in their territories.

“To me it’s a great big win, win, win. We can have reconciliation occurring on the lands, which I believe would then push the government to more substantive reconciliation from a legal and political perspective.”

Late last year, facing ferocious opposition from the coalition, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers denied a key permit for the Pebble mine, concluding the project would significantly degrade the surrounding environment and was not in the public interest. But the company didn’t take no for an answer and appealed the decision. Its website, which describes the project as the most significant undeveloped gold and copper resource in the world, says the mine “is in federal permitting” and “is being advanced towards development” by Northern Dynasty.

On Sept. 9, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency dealt a serious blow to the company’s plans, saying it would invoke powers under the Clean Water Act to ensure the Bristol Bay region’s waters are not filled in or contaminated by material from the mine. The company’s media contact number directs reporters to a company called Hunter Dickinson, which did not respond to a request for comment by time of publication.

Hurley points to the 14,000 long-term, sustainable jobs fueled by Bristol Bay’s salmon industry, compared with several hundred short-term jobs offered by the mine. “Salmon are such an essential part of our being, our way of life. There’s just no way that our people can continue our way of life here if our water, and our fishery is poisoned and toxic. For us it’s being able to continue being Native people in Bristol Bay. Which is why we’ve never, ever backed down.”

For Bristol, protecting salmon runs all over the Pacific Northwest comes down to tough choices and hard calls. “Salmon are incredible and they are resilient but they can only take so much,” he says.

“We’re just going to have to decide as a society whether we want to have wild salmon in our lives moving forward — and now’s the time to be starting to have those conversations and thinking about making those tough choices.”