Early this spring, employees of the denim producer Candiani dug a dozen holes into the rolling hills and forests overlooking the Ticino River. They were there to bury brand new blue jeans.

“The lab tests had already shown that our new jeans are compostable,” sustainability manager Danielle Arzaga says, “but we wanted to test it ourselves to be sure.”

Labeling something as compostable is a dirty trick many fashion labels use when their products only “compost” in special high-temperature commercial facilities. But when the Candianis dug up the jeans again six months later, they discovered the fabric had mostly degraded to earth. Alberto Candiani, the fourth-generation owner of the family business, had developed the first fully biodegradable denim, called Coreva.

“That doesn’t mean your jeans will fall off if you get rained on,” Candiani qualifies with a laugh. “They are extremely durable, but at the end of their life, yes, you could send them back to us and we recycle them, or you could fertilize your veggies with them. We have even fertilized cotton fields with our scraps.”

Jeans are among the most popular clothing on the planet — and one of the most environmentally taxing. Each pair requires up to 2,000 gallons of water to manufacture. And to produce Indigo blue, the dye that gives jeans their color, almost all manufacturers use benzene (a rat poison), mercury and other toxins. What’s worse, 80 percent of jeans sold nowadays are stretch denim, made with plastic — researchers have even found plastic microfibers from jeans in the Arctic. Overall, the fashion industry is responsible for 20 percent of global wastewater and 10 percent of carbon emissions worldwide. “Most jeans take hundreds of years to degrade,” says Arzaga. “Our stretch denim takes six months. We’ve created a truly circular model where materials can return to the earth naturally at the end of their life.”

The Candianis have been pioneers of sustainable fabrics since the 1970s, long before sustainability was fashionable. They were propelled onto this journey against their will. When the Lombardi region was declared an environmentally protected area 50 years ago, “my father thought the restrictions were nuts,” Alberto says. The family’s factory was located in the middle of the new nature reserve, between Milan and the Alps, and the Candianis thought the new environmental standards would be impossible to achieve. “We still have to test our water weekly,” Arzaga says. “I don’t know of any other manufacturer who has to do that.”

Candiani is now the biggest denim producer in Europe to survive the exodus of textile production to countries like India and Bangladesh. “We’re the last man standing,” says Alberto from his home in Milan. “My dad always says, efficiency is the grammar of sustainability. What we thought was a disadvantage has turned into an advantage.”

By necessity, Candiani managed to reduce water use by 75 percent and the use of chemicals by 65 percent. “We collect and reuse 100 percent of our waste fibers for our recycled denim line,” Alberto says. “It is possible to produce a pair of jeans with 20 or 30 liters of water.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.To reduce chemicals, Candiani bought the patent for a new technique to produce deep Indigo with the help of a natural fungus. And instead of synthetic polyvinyl alcohol that binds the fibers with a liquid plastic film that can shed microplastics, Candiani uses a biobased polymer. “There is no reason for us to create microplastics anymore. We are going plastic free,” Candiani says. “Chitosan is also used to purify the water, which makes it super smart.”

You might not know the brand name Candiani — they have only one store in Milan where they sell custom jeans directly to consumers — but if you’re a consumer of sustainable clothes, you probably have their denim in your closet: Candiani is responsible for the sustainable denim offerings of major brands, including Lee, Levi’s, Lucky Brand, Hugo Boss, JCrew, Stella McCartney, Diesel, Closed and Outerknown.

There is a downside: The labor and production costs make the Candiani denim significantly more expensive. “We charge about six dollars per yard,” Alberto admits, about double the price of conventional denim. “Labor cost alone is a third of the cost.” If he outsourced production to, say, Bangladesh, labor costs would be about 1/100th what they are in Italy.

But as a family business with century-old ties to the region — and grandma Candiani still living on-site — moving is out of the question. In fact, Candiani hopes to bring the cotton sourcing closer to home and even tried to grow organic cotton in Italy instead of India or Africa. He is currently experimenting with growing cotton through regenerative farming and engineering his own cotton seeds. He hasn’t succeeded — yet. But Alberto is convinced it will just take a few more years of trial and error, just like developing the compostable Coreva denim took five years.

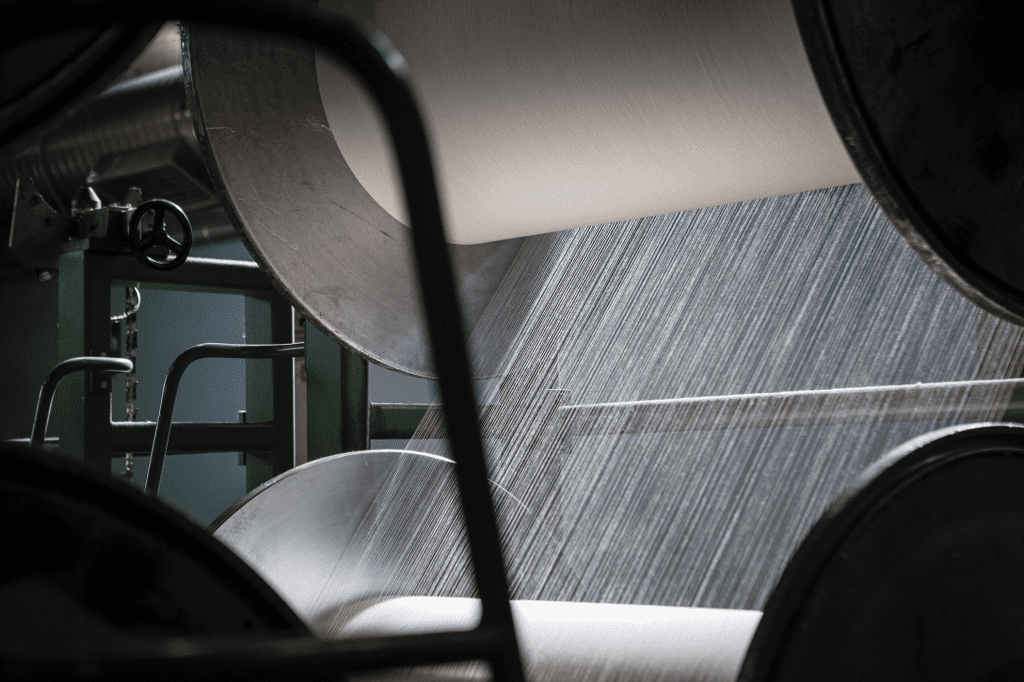

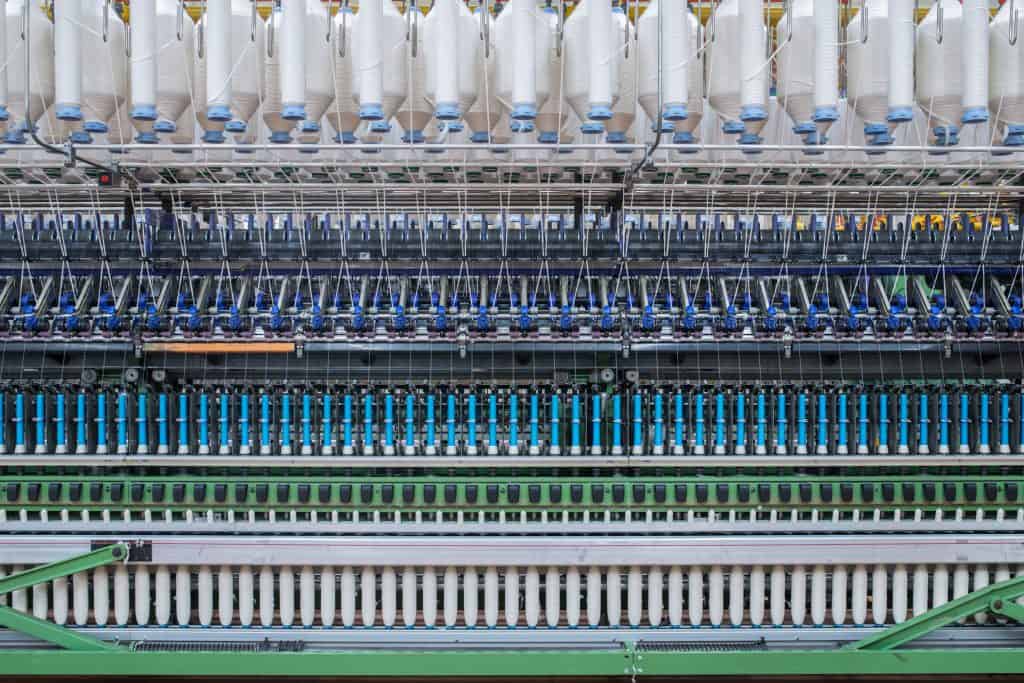

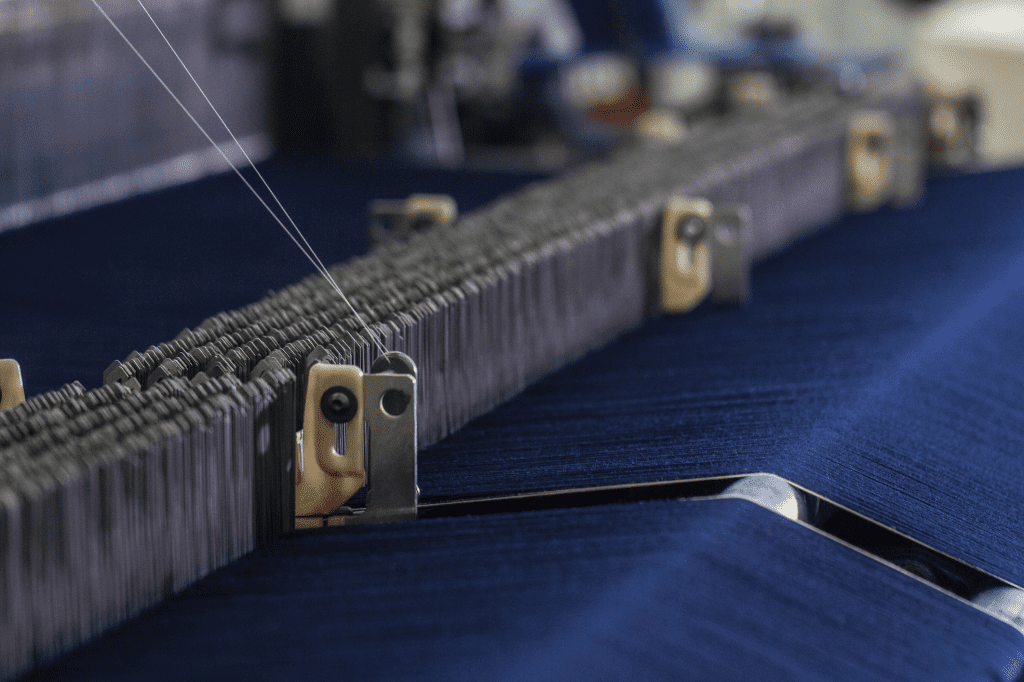

Alberto Candiani is an unlikely eco-pioneer. He became a professional techno DJ and music producer, and toured with his heavy metal band before taking the helm at the company in 2000. “My father started to get seriously worried,” jokes the trim company president with the salt-and-pepper beard. “But I literally grew up in the mill, and I still think of it as a playground.” It was the rubber packaging of salami at the local delicatessen stand that gave him the idea to use natural caoutchouc for denim yarn. “Something clicked. Because it touched food, the rubber had to be free of toxins, so I knew it was possible and that it could change the world of stretch denim forever.” In the mill, giant rolls of white yarn feed into industrial-scale looms. In another room, the needles weaving the denim stitch with a low rhythmic hum that almost sounds like percussion.

Alberto’s great-grandfather Luigi Candiani started the business in 1938 with a single loom, first as a simple weaving facility that wove workwear fabrics to be sold at the markets in Milan. His son, Primo Candiani, transitioned to premium denim. Alberto’s father, Gianluigi Candiani, recognized the potential of stretch denim and took the business international. He still lives on site, makes the rounds daily, and in the evening he shares a bottle of local wine with his long-term employees.

What the founders thought was a catastrophe — the highest environmental standards any textile producer could face — has become a unique selling point that allowed their business not only to survive, but to triple production. Their denim operation is sometimes called “the greenest mill in the blue world.” And their denim formula has been awarded Global Organic Textile Standards GOTS approval and won numerous awards.

A small design center in Los Angeles, where Alberto’s wife Chandra is from, is the only Candiani facility outside of Italy. There, the jeans are washed with small stones instead of toxic chemicals to achieve a distressed look. The repurposed warehouse looks like a giant laundromat with its ocean-blue washing machines. U.S. director Damiano Dall’Anese meets with brand designers to create the style they’re looking for, whether the denim needs to be hand-sanded or lasered. “You can be as green as you want but if the product doesn’t look good, it doesn’t matter,” Dall’Anese knows.

Alberto believes the key is a blend of heritage and innovation. “Milan is the fashion capital of the world, and Los Angeles is the design capital of the world,” he says. Many think of jeans as the quintessential American clothing, but they were actually invented 500 years ago in Genua, Italy — the word “jeans” has its origin in “Genoese.” It’s only fitting that an Italian legacy company forges a new green way to go blue.