Can we change our behavior or are we stuck?

The good news is that the answer appears to be: yes, we can change. We’re not doomed to repeat destructive behavior. We can change our habits.

How do we come to change our behavior? Does the arc of our actions tilt towards beneficial behavior, or does it oscillate wildly? Is there a methodology—a tried and true means and model that has been used and proven successful to turn us towards more constructive habits?

I’d like to look at a few places where people’s behavior has changed for the better and see if there emerge any common techniques or conditions that allowed those changes to happen. I’m curious whether, if one “zooms out,” broadly applicable processes reveal themselves.

A good place to start could be Melbourne, Australia.

Changing water use, changing people

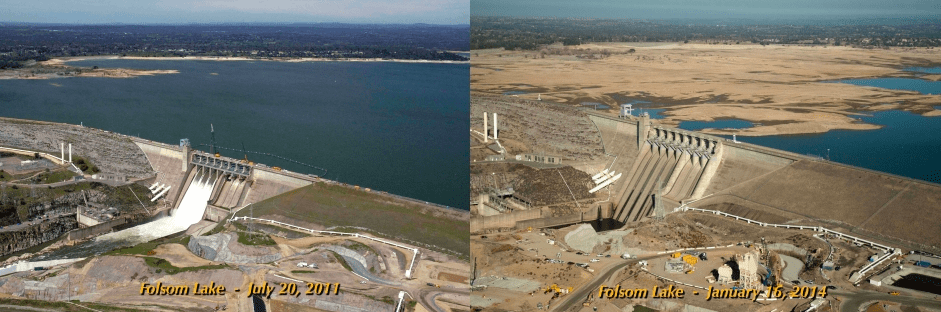

In the late 1990s and early 2000s Melbourne had a severe drought. The city was 500 days—a year and a half—from running out of water. When that happened, people would pretty quickly have to pack up and leave. Many of us will face these kinds of choices—hello L.A., hello Phoenix, hello Lima, hello São Paulo. Look at what’s happening in Chennai, a city of 7 million-plus people in India, where water has already just about run out and only those who can afford to buy it from trucks get the drinking, cooking and washing water they need. So what they did in Melbourne to solve their water crisis is relevant to other cities.

“Trees were dying in the parks,” said Sandie Pullen, who then was the manager of water communications at the state Department of Sustainability and Environment. “There were dry creek beds with animal skeletons on the outskirts of Melbourne.”

In Melbourne everyone knew something had to be done, and they realized that they’d all have to do it together. Sadly, it often seems an emergency or crisis is what it takes to get folks on the same page.

Even as they were ready to tackle the problem, however, they weren’t sure what to do. How can you change people’s water usage habits? There was no time to build another desalination plant—curtailing water use was their only option.

Here’s what they did

The utility Yarra Valley Water conducted a behavioral study to come up with an effective campaign to change public habits around water consumption. According to the Times, Yarra Valley’s communications manager “went on a tour to learn from experts across Britain, Canada and the United States, and then hired two Australian psychologists who specialized in behavioral change to help identify which behaviors to target, and how.”

In 2008, the utility launched an advertising campaign to promote a target of using just 155 liters (41 gallons) of water per person each day, and to strengthen social norms around using less water. The residents were barraged by bus ads and street posters.

But advertising was just one component. The city gave out shower nozzles that used less water. Why shower nozzles? In their research they found that many folks did NOT want to take shorter showers… that would be too tough a sell. So instead, they offered residents free low-flow shower heads. Same time in the shower, less water. Some 460,000 shower heads were replaced over four years in a city of 1.3 million homes.

Some people complained that the new shower heads didn’t match their decor, so the city said, fine, here’s an adapter, you can use this to reduce your water flow AND keep your existing shower head.

Melbourne also offered rebates if folks bought or switched to water-efficient washing machines, 365,000 of which were installed. Same for rainwater tanks—and nearly 30 percent of households began using them. The staff at 80 garden centers were trained to help customers learn about planting drought-tolerant native plants and mulching their gardens to hold in moisture.

They also used a psychological “nudge” technique. When residents got their water bills, it told them not only how much water they used, but how much their neighbors were using. This was very effective—people don’t want to look bad in comparison to their neighbors.

Did it work?

Yes. Residents use 60 percent of the city’s water, so getting even some of them to use less went a long way. Domestic water consumption dropped from 247 liters (65 gallons) per person daily to 147 liters (39 gallons)—and the city’s reservoirs stabilized and slowly replenished. Deep breath.

Quoting two of the psychologists involved in creating the behavioral study, Rob Curnow and Karen Spehr, the New York Times writes: “The underlying message was ‘we’re all working together to save water,’ Spehr says. This fostered a ‘sense of fairness and collaboration in saving water.’ The fact that many of these water-saving initiatives were done with, and not to, the people of Melbourne was crucial, Curnow and Spehr said.”

There was a fear, however, that once all this campaigning ended and rains came, everybody would return to old habits. But they didn’t. Water usage bounced back a little bit, but not by much. In fact, Melbourne’s residents never returned to using as much water as they once did. They now use 44 gallons per person daily—which sounds like a lot, but in Los Angeles it’s 84 gallons.

Here’s Raymond Joseph, an opinion columnist for CNN who lives in Cape Town, where they came perilously close to “Day Zero”—no water:

Today… saving water has become the new normal for many Cape Town residents.

Like so many other households, my family still takes two-minute showers or inch-deep baths. Afterward, the water is scooped into buckets and used to flush toilets and water plants.

It is also no longer a reflex habit to flush the toilet after urinating, even when using a public toilet—something that outsiders who have not experienced what we went through find difficult to come to terms with…

An example of how much water is needlessly wasted was illustrated in a study by a young University of Cape Town researcher, who found that enough potable water to fill eight Olympic-size pools was flushed away in urinals on the campus each year.

Taps remain switched off in many public buildings and privately owned offices and shopping centers, where waterless urinals, hand sanitizer and signs reminding people to save water are commonplace.

But there was also an upside to Day Zero: It sparked innovation and a huge growth in companies offering water-saving products, such as waterless toilet and urinal solutions.

L.A. and other U.S. cities will face these same choices very soon. Will it take an emergency to get everyone to pull together? Maybe so, but the good news is that habits in Melbourne and Cape Town that changed in response to an emergency were, for the most part, changed for good.

What can other cities learn from this?

A report by the Alliance for Water Efficiency emphasizes the crucial role of public communication in influencing the public’s behavioral changes. The report confirms that communication, promotion and outreach of water conservation campaigns “helped to maintain strong community support for water restrictions” leading to lasting changes in behavior.

We CAN change our behavior and habits—as humans we’re adaptable. This malleability allows us to be swayed and seduced by demagogues, but it also allows us to adopt more positive behaviors. The hope is that we will, over time, tilt towards behaviors that benefit us all in the long term.

In my next story in this collection, I’ll look at how movies and theater have been used to change behavior in India to reduce outdoor defecation. Stay tuned.

This story is part of a collection called Changing Behavior: Stories about learning to grow in ways that benefit society. Read more here.