Insects flit from flower to flower. Tall grasses sway in the breeze. Paths meander through the greenery, and the dappled shade of potted trees dances in the sunlight. But this is no ordinary garden. This is one among nearly three acres of new blue-green roofs — with meadows, vegetable gardens and wilderness — spread out atop buildings in Amsterdam. They are designed to increase biodiversity, cool the neighborhood and prevent flooding in the streets below.

From 2018 to 2022, the city — which has tested the concept for a decade at small scales — installed “smart” blue-green roofs in four flood-prone neighborhoods. Assessment of the project so far shows the model is effective at mitigating damaging storm runoff and combating the urban heat island effect.

Like many cities, Amsterdam is facing periods of heat and drought in the summer, coupled with extreme storms and flooding in the winter. In Europe, temperatures are warming faster than on any other continent in the world — at more than twice the global average rate. Meanwhile, Northern Europe’s winter weather is trending to more extreme precipitation and flooding.

Over a quarter of properties in Amsterdam are at risk of being severely affected by flooding over the next 30 years.

The Netherlands has long been looked to as inspiration for innovative flood management amid climate change. Many of the country’s solutions are large-scale infrastructure projects, but according to Kaspar Spaan, policy developer for Dutch water company Waternet, more pinpointed efforts like blue-green roofs are also critical for Amsterdam’s adaptation.

“The classic response was to go bigger — with higher dykes, floodgate barriers,” says Spaan. “Now, we understand the need for micro-water-management.”

Going small

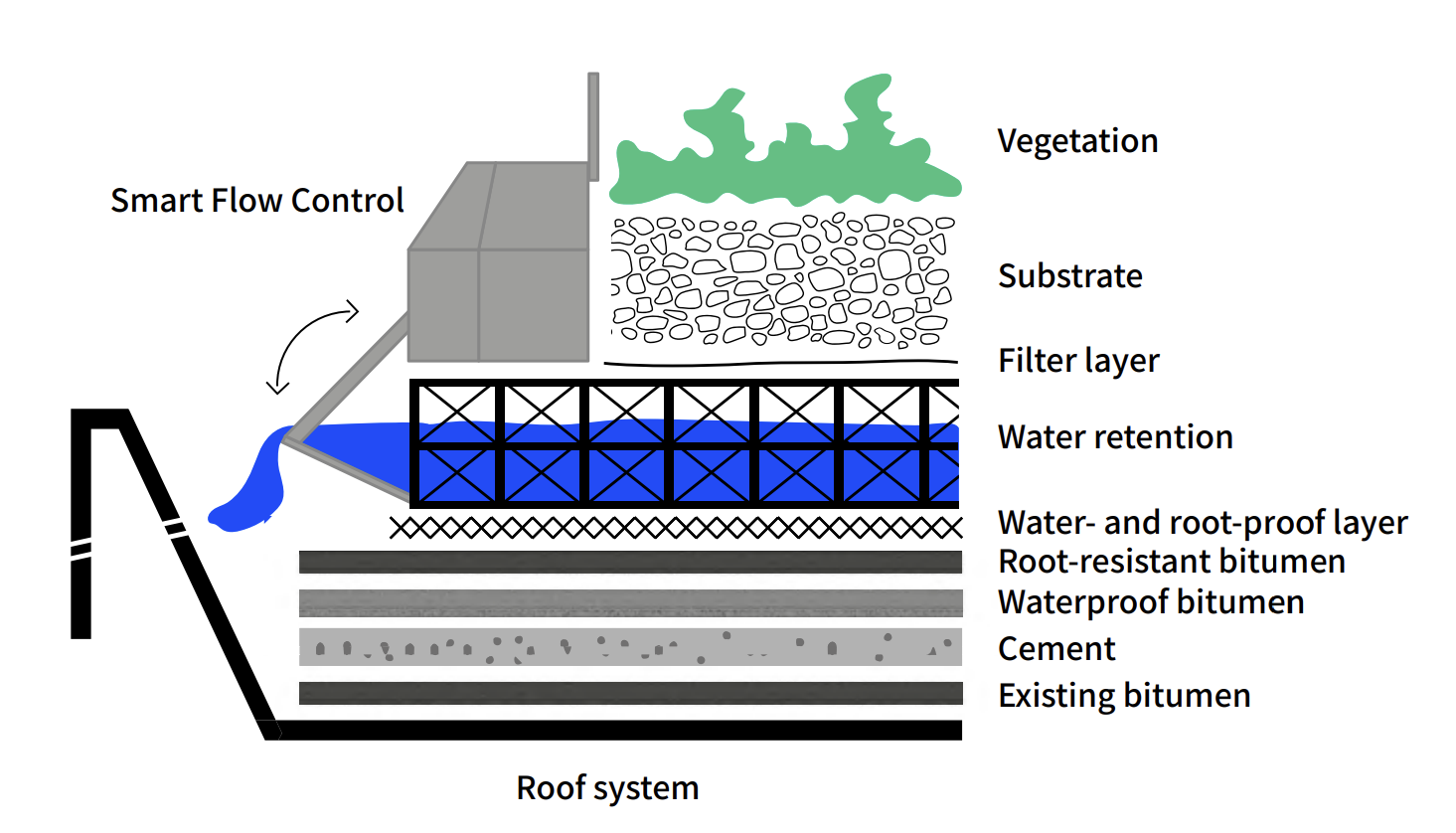

Simple roof water collection systems — or blue roofs — are designed to store rainwater and to mitigate runoff impacts. When combined with green roofs, you have the added benefits of lowering urban air temperatures during heatwaves and boosting biodiversity. For the recent Amsterdam project, dubbed Resilio, the Dutch added a “smart” factor, connecting multiple blue-green roofs via a digital network.

“Now, we have the capability to control the water level on each roof system separately,” says Spaan. “We can [respond to] seasonal fluctuations and drain the system in winter or collect more water in spring and summer, creating a buffer for future droughts.”

Each roof has a smart valve which, explains Tim Busker, is part of an “ingenious” computer system called the Decision Support System (DSS). Busker, a researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam’s Institute for Environmental Studies, explains that a closed valve maintains storage of rainwater on the roof to nourish the plants. The valves, he explains, are connected to real-time weather forecasts and open when precipitation is expected. The system then slowly releases water into the city sewers. This prevents the city drainage system overflowing and avoids the kind of infrastructure damage that comes with flooding. And that leaves the blue-green roofs’ holding layer empty and ready to accept the next downpour.

“The DSS also takes other factors into account,” says Busker, “such as neighborhood characteristics or different seasons. For example, near a hospital it is of the highest importance that the roads are not flooded. So, the valve can be configured to be more sensitive to the rainfall forecast and open more frequently, ensuring enough capacity is available to store the incoming downpour.”

A study of Resilio’s blue-green roofs found they could capture up to 97 percent of extreme precipitation — considerably more than a conventional green roof, which typically captures around 12 percent, and more than conventional blue-green roofs, which capture around half.

“In the Resilio system,” says Spaan, “we aim for 60 to 70 millimeters of water storage. In the Netherlands, that’s considered a very heavy downpour — the sort that only happens once every 50 years or so.”

During hot, dry spells, the water collected on the roof serves many purposes. It irrigates the greenery, and the extra insulation the layer of water provides keeps the building cool too. The study suggests this could lead to less energy consumption of the people living below.

“The heat stress [during hot weather] in the top level apartments was seriously reduced,” says Spaan.

Going green

The Resilio system has the potential to lower temperatures by 0.3°C at street level, too — helping to reduce the urban heat island effect.

“You can cool the city as a whole by providing more evaporation and transpiration of plants,” says Anna Solcerova, a researcher in water management and urban climate at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences.

Blue-green roofs allow for much higher evapotranspiration (water transferred to the atmosphere by evaporation) rates than conventional green roofs — at around 70 percent — which reduces heat stress in the city as a whole.

“There is a rule of thumb that for every 10 percent more surface coverage of vegetation, you cool the city by half a degree,” says Solcerova.

Plus, Resilio’s roofs are also suitable for growing a wider variety of plants than conventional green roofs.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.“If you want a green city with biodiversity and vegetation quality, water availability is the key,” says Spaan.

While traditional green roofs need drought-hardy plant species, the water availability of Resilio’s blue-green roofs allows a greater range of indigenous vegetation to survive. “With the capacity of 60 or 70 millimeters, indigenous plants can withstand droughts for up to four weeks,” says Spaan. This in turn attracts a higher diversity of insects. These flourishing green spaces offer a resting or foraging place for wildlife — such as bumblebees, butterflies, spiders, birds and bats — and act as an ecological corridor for wildlife populations previously separated by human activity or structures.

The new standard

Now, the question is whether the concept can be scaled up even further.

“We have a saying,” says Spaan. “Not on every roof everything is possible, but on every roof something is possible.”

Many roofs of older real estate developments are unable to take the full weight of a smart blue-green roof.

But, says Spaan, you can get the water storage “buckets” in any size you want. In addition, removing things like pebbles from a roof allows you to replace that weight with the weight of water.

Cost is another sticking point. Resilio was publicly funded. But there could be incentives for private buildings to invest. In dense urban landscapes, Solcerova notes, “Every outdoor space is highly valued and very scarce.” A smart blue-green roof with an accessible garden with a view or recreational area is projected to add up to 21 percent to the property value.

The Resilio team has already shared their knowledge and experience with other European cities and, says Spaan, similar projects are sprouting all over the world.

“We see blue-green roofs and similar concepts scaling up in cities such as New York, in many parts of Europe, South Asia and Canada,” he says. “It all starts with water. It’s a concept that is growing to be the new standard.”