The terms “Republican,” “pro-cycling,” and “suburb” don’t traditionally go hand in hand. But the (Republican) (pro-cycling) mayor of (suburban) Carmel, Indiana, James Brainard, finds that notion laughable. Why? It’s simple: cycling makes economic sense, he says, if you design for it as comprehensively as you design for cars.

His town is living proof.

It all started with the Monon Trail, a former railway bed that was converted into a recreational trail starting in the early 1990s. The trail runs between Indianapolis’s downtown area and its northern suburbs, one of which is Carmel, population 92,000, about 15 miles north of the city. Today about 1.3 million people ride the trail’s 20 miles in the Indianapolis area each year.

That wasn’t always the case. When the Monon Trail was first being converted, Brainard, who took office in 1996, was surprised to see it was getting less use than expected. He wondered why. It seemed to be perfectly positioned, running right through the center of town, linking housing and retail areas within the suburb, and connecting Carmel to neighboring cities to the north and south.

Then he realized the reason was staring him right in the face: Carmel was treating the Monon Trail like a recreational bike path when it should have been treating it like a road.

“We found out it was in the right place, cutting right through the center of town, within two miles of the arts district and the downtown area and municipal buildings,” says Brainard. “But we noticed people had to drive their cars with their bikes on board to get to it. That’s right, people couldn’t ride their bikes on this great trail unless they loaded up their cars with their bikes and drove to it.”

What Brainard was seeing is a common problem: many cities view cycling as a recreational pursuit, not transportation. Accordingly, bike trails are often set apart from the rest of street networks, in bucolic settings that are good for exercise, but not very practical for getting to the grocery store or to work.

This mindset isn’t just a local-level problem. In the U.S. Federal Highway Administration’s Small Town and Rural Multimodal Networks guidelines, routes like the Monon Trail are described as providing “nonmotorized transportation access to natural and recreational areas,” and only “in some cases, a shortcut between cities and neighborhoods.” The guidelines dedicate several pages to the physical design of bike lanes, but far less attention to how these lanes should be integrated as transportation corridors on par with roads.

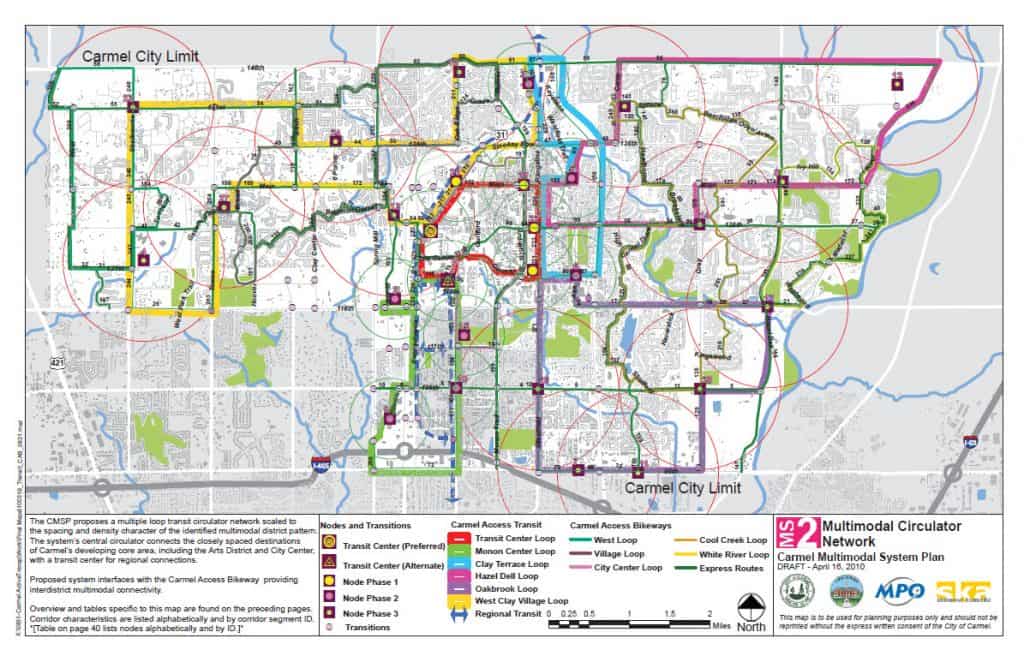

Carmel decided to change this. They started thinking of the Monon Trail as a major highway. Multi-use roadways with bike lanes were built, connecting the trail to the street system. Real estate developments with new housing were required to build bike paths around them. A 100-mile network called the Carmel Access Bikeway took shape, with 10 times more miles of routes than the previous network.

In addition, parking garages were required to have bike racks, as were sidewalks in the downtown area. New buildings of five stories or more were encouraged by the city administration to face their main entrances toward the trail, rather than toward their parking lots. These new buildings are also required to have showers available for those riding their bikes to work.

In other words, Carmel gave its bike trail the same infrastructural features that any highway for cars would be given automatically.

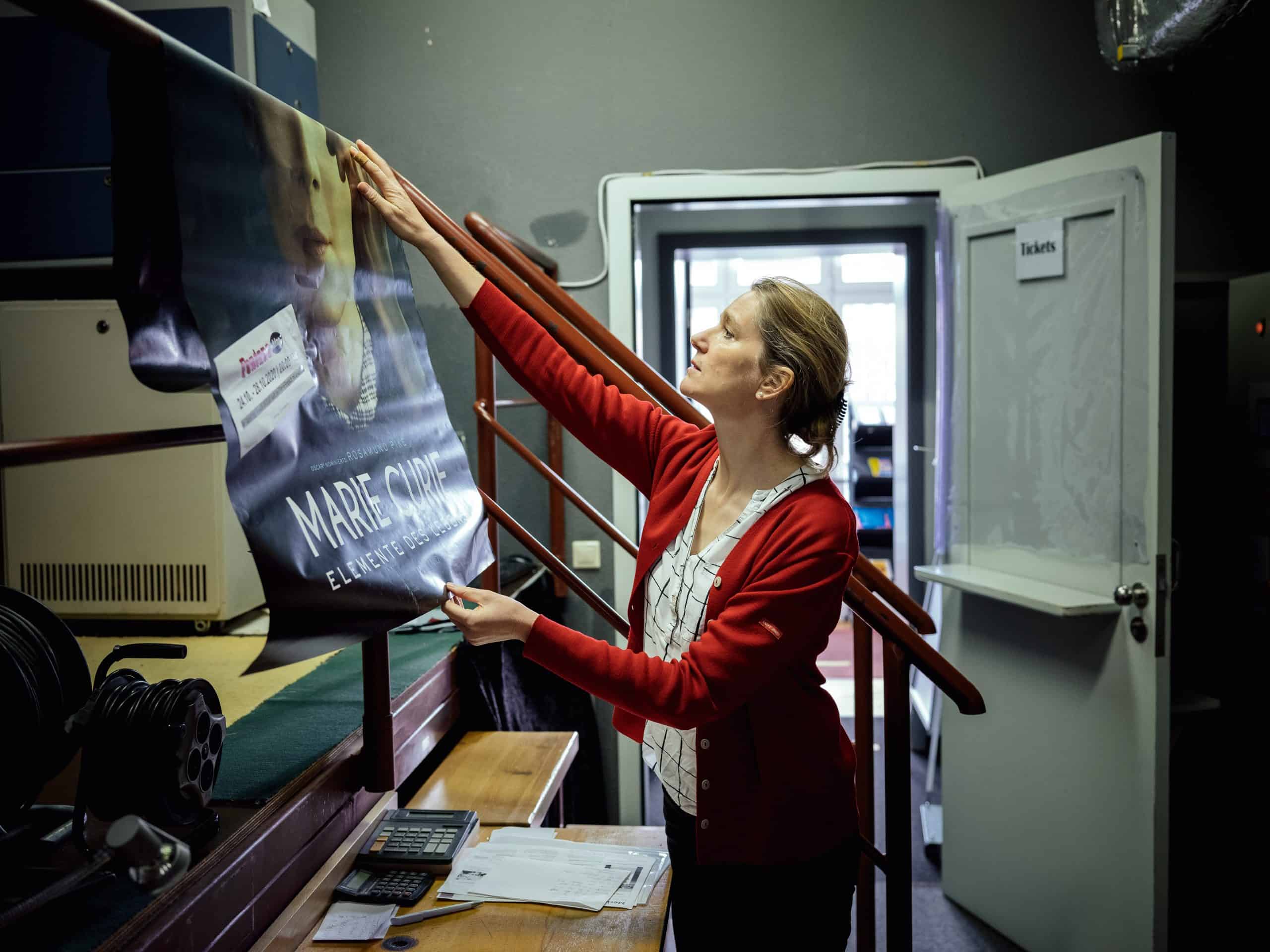

Kevin Whited, the city’s transportation development coordinator talks about the broader change in thinking catalyzed by the infrastructural upgrades.

“A lot of it is a culture shift,” says Whited. “You can get the infrastructure down, and that will get a certain number of people to ride. Then members of the community start using this infrastructure and it has this trickle-down effect.”

“We are still finding that businesses and people who want to move here are asking about school districts, city services and tax rates as they always have,” he continues. “But now they are also asking about the transportation choices they have. Being able to ride a bicycle to work or to go grocery shopping is more and more a part of that. They are asking us about that and are surprised with what we have.”

Mayor Brainard hears the same pleasantly surprised responses. He’s often asked how the conservative mayor of a suburban town in a deep-red state, in a county that has voted for a Republican president in every election since 1916, could possibly be “pro-bike.” To him, it comes down to good economics, good urban planning, even good politics.

“First, I’ve been a bike rider myself for a long time,” he says, “and I get how it should be part of the transportation system, not a hobby. But, secondly, there is no conservative or liberal way to provide good city services. The cost of building roads is a huge amount of money, and if we find our people want to use bicycles to get from one place to another, it is up to us to build the infrastructure economically that allows people to do that. That is basic city service economics.”

Those economics are now penciling out. A 2017 study by the Eppley Institute for Parks and Public Lands found that economic development is ballooning in areas near the bike access trails. In 2001, Carmel riders spent about $1,000 a year on “trail-related expenditures”—such as food, clothing, bicycle gear at local merchants near the trail—while riding. That number has since grown to about $4,000 a year.

Meanwhile, participation in the city’s Bike to Work Day has grown by 500 percent in four years. Shopping trips by bike appear to be rising, too. Twenty years ago, the city counted about 10 to 15 bikes parked at the Carmel Farmers’ Market on Saturdays. Since the surrounding bike lanes were improved around it and a corral for bicycle parking was added, they now count 300 to 400 bikes on the average weekend.

“When we started thinking about bicycling differently, most thought that the bike paths we were advocating were just going to go nowhere, and they meant that literally,” says Carmel Councilman Bruce Kimball. “Eventually we wanted to connect to every neighborhood, because we found that many people were rethinking how they move from place to place… And we are seeing that very clearly in their spending habits. They are using their bicycles instead of their cars, using them for shopping and basic travel needs, and not just for a workout on the trail.”

Carmel now has more than 200 miles of bike paths and trails in its transportation infrastructure network, up from about 100 miles in 2010. It is now possible to safely access every part of the town by bicycle. In 2017, from June through September, 80,000 total users were counted on the Monon Trail in Carmel alone, about 45 percent of whom were cyclists. By contrast, in 2001, the number of total users was less than half that, and cyclists were an even smaller share at only 21 percent.

Cities like Boulder, Seattle, Cambridge and San Francisco are celebrated for their cycling infrastructure, but the real challenge is to import that thinking to suburban areas like Carmel. Slowly but surely, it appears to be happening. The League of American Bicyclists, which ranks communities based on how cycling friendly they are, has seen a sharp rise in the number of suburban towns applying to be recognized. In the group’s latest count, 464 places qualified as Bicycle-Friendly Communities, with “great diversity among successful applicants, from small towns such as Battle Lake, Minn., to large metropolitan areas such as San Antonio, Texas,” according to program director Amelia Neptune.

“One of the things smart cities are doing is not drawing a distinction between riding a bike for transportation purpose and a recreational one,” says Darren Flusche, a senior planner for transportation consultancy Toole Design. “What it boils down to is having a well-connected transportation network, and if you are distinguishing how it is used, you are missing the point.”

Mayor Brainard says that’s exactly the thinking that made Carmel the cycling-friendly suburb it is today. “What we kept hearing from our citizens is that they wanted a walkable and traditional downtown area,” he says. “They wanted for us to have planning that accommodates cars, but is not designed for cars.”

“I think that is what a lot of cities are missing,” he continues. “For many different reasons, people do not want to be wedded to their cars like they used to be. They don’t want to get rid of their cars, either, but they want to live in cities that have other transportation options. Biking is another option now. And it needs to be treated that way, in a very real and consistent manner.”