Arizona State University in Tempe is a key part of daily life for Terrie and Dave Sanders. They attend classes, concerts, plays and sports events, taking advantage of their ASU Sun Cards to get free or discounted tickets. They stroll the campus and grab lunch in the student union. They live on campus, like many of their classmates, and they chat with them about courses, majors and life goals.

But quite unlike the vast majority of students around them, the Sanderses are in their late 70s. Their undergraduate and grad school years and full careers are behind them; each has adult children and grandchildren. Two years ago, the couple moved out of a spacious house in a Phoenix-area adult living community and decamped to Mirabella at ASU, a 20-story continuing-care retirement community that opened on the ASU campus in December 2020.

“We were happy in our community,” Terrie Sanders says. “But when we heard about Mirabella opening, we came and looked, and got really excited — and not for the future, but for right now, because of the vitality and activity that it offered, because of the college campus opportunity.”

University-based retirement communities, or UBRCs, have gained popularity as more Baby Boomers retire. Many are simply 55-plus-style developments near colleges. But Mirabella’s on-campus location is part of a newer, growing trend that can more easily foster daily intergenerational connection. At SUNY’s Purchase College, an on-campus senior living facility is expected to open in fall 2023. In Maryland, Goucher College is considering a plan for a nearby senior living community to expand onto the campus. These arrangements — along with other intergenerational initiatives across the US — promise benefits for old and young, warding off loneliness for the former and providing additional learning opportunities for the latter.

An antidote to isolation

Even before the isolating effects of the pandemic, research showed that loneliness can lead to depression and poor health in older people, and experts in aging have sought ways to increase social contacts for elders. Studies in Japan and in Portugal found that intergenerational programs — connecting old and young people — could serve as key health and self-esteem promoters for elderly participants.

A 2018 report by Generations United, a US organization that studies and promotes intergenerational connectivity, cites a range of benefits for older people, from reduced isolation and frailty to a greater sense of alertness, purpose, achievement and self-worth.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.“When older adults are with just each other, talk turns to the three p’s — pain, pills and passing — what hurts, which medicines, and dying,” says Generations United Executive Director Donna Butts. “With intergenerational relationships, the conversations are richer and deeper.”

The Sanderses attest to the different energy being around younger people brings.

“We don’t feel at all like we’ve moved into a ‘home for older people,’” says Terrie Sanders. “It’s a really exciting environment. And you get to know the students working in the dining room. We talk to them about what they’re doing, what classes they’re taking.”

What’s more, it’s a two-way street: Cross-generation connections benefit the young, too.

“We all want someone who’s going to cheer us on — and for students, to have an older friend or role model or tutor is extremely helpful,” Butts says, “especially when you think about international or first-generation students who don’t have support nearby or don’t have family with college experience.”

Students who have meaningful connections with older people also are more likely to remain interested in aging and gerontology — crucial fields of study and work as the US population ages.

In Newberg, Oregon, Friendsview continuing care facility has a relationship with nearby George Fox University whereby live-in volunteering arrangements connect physical therapy students with elders. Kendal at Oberlin senior living community in Ohio has a web of intergenerational programming in the community that includes work-study, volunteer, and live-in programs with students from Oberlin College and nearby community colleges and vocational schools.

Generations United has compiled a comprehensive toolkit for others seeking to develop effective intergenerational programs in senior housing organizations.

“Intentionality is important,” Butts says. “You can’t just plop a senior living center down and assume the connections will happen.”

Challenging stereotypes about aging

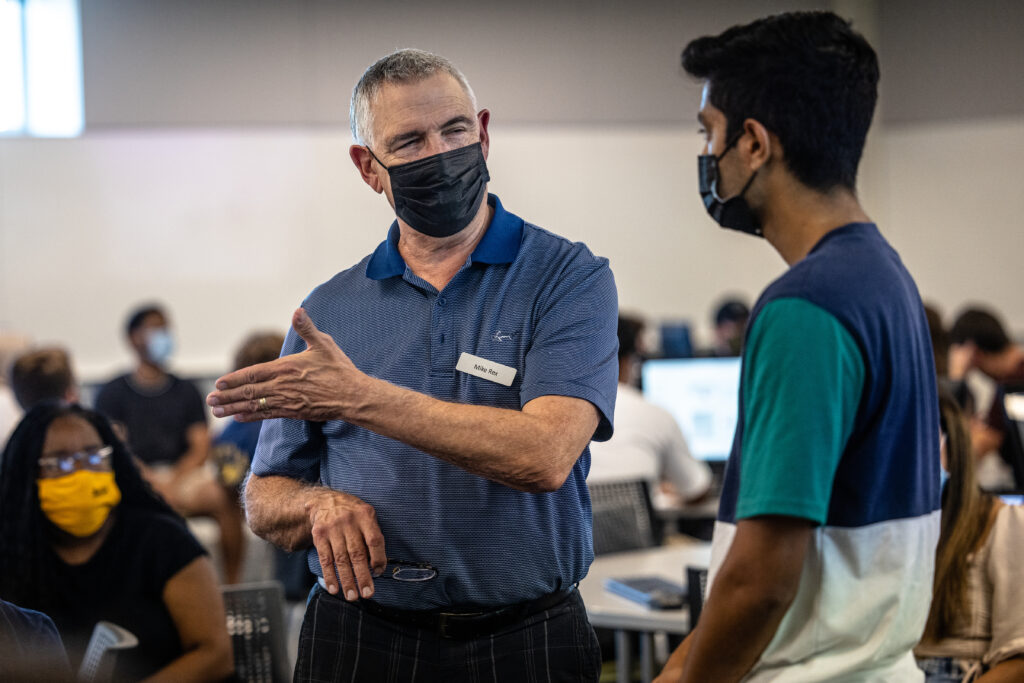

At Mirabella, collaboration with ASU and the older residents themselves has created a wealth of programs intended to foster deep intergenerational ties. Lindsey Beagley, director of lifelong university engagement at ASU, says a pen-pal program has drawn some 50 students who have been matched with an elder for email exchanges. These connections can blossom into in-person friendships. A group of retired physicians living at Mirabella formed a mentoring group that has drawn more than 80 pre-med students to discuss topics like medical career paths and physician burnout. About 100 of the 260 residents have taken ASU classes, from languages to geology, religion and archaeology.

“These folks are challenging all our assumptions about what retirement can look like,” says Beagley. She’s been impressed to witness residents “willing to fumble with new technology or struggle through Spanish 101 alongside 19-year-olds — and love it.”

Michelle Kim, a doctoral student in ASU’s collaborative piano program, moved into Mirabella in August 2021 as part of a Musicians in Residence program, in which music students can receive room and board in exchange for music performances, lessons and choir leadership. Kim interacts with residents in numerous ways besides piano lessons.

“A lot of younger people have a pre-notion of old age, and certain stereotypes that old people are boring and inactive, but that is totally not the case,” says Kim. “I have had some of my greatest times with the residents, going out to dinner, watching shows, playing sports together and making music together. Hopefully, my experience can [help] break the preconception that younger people have about older generations.”

Older Mirabella residents, for their part, express keen interest in the goals and accomplishments of the young employees and classmates they get to know.

“A woman who works in the dining room sings a cappella. Her group is going to perform here, and I’ll be there for her. And today I’m going to ASU to see a student’s doctoral performance, to support her,” says Shelley Malinoff, 74, a retired audiologist and music lover who has lived at Mirabella since December 2020.

Malinoff takes piano lessons, helps bring hearing science students to Mirabella to conduct hearing screenings and give presentations on living with hearing aids, and has pursued ASU courses on religion, Ursula Le Guin and the geography of wine.

“It’s great being in the classroom, and wonderful also that we have college students in the dining rooms. I can mother them all, and they help me,” she says.

In one instance of the young bringing the old into the modern age, Malinoff recalls, students “mortified” to see her using earbuds with a cord quickly introduced her to the benefits of AirPods.

Healing cultural divides

Retirement living on campus doesn’t come cheap, of course. Like many “life plan” communities that offer progressively more assistance and medical services as needed, Mirabella residents buy in with an upfront fee that ranges from $450,000 to $2 million and then pay a monthly fee of $4,500 to $5,000 that covers dining, utilities, housekeeping costs and programming. University officials say they’re not in it for the money — ASU leased the land to Mirabella’s developer/operators for an upfront fee, but it does not garner revenue from the retirement center now.

A few creative affordable options are emerging outside the campus-based model, though. Generations United’s Butts cites an example: Bridge Meadows in Oregon creates residential communities where lower-income seniors live alongside families adopting or fostering youth, and gain affordable housing in exchange for volunteering their time with the families.

And finally, beyond its benefits for individuals and families, intergenerational programming holds potential to bridge some of our modern cultural divides.

“One of the reasons we advocate so strongly for intergenerational connections is the changing demographics in our country,” says Butts. “We have an aging population, but we also have a growing younger generation. The older people are more likely white, while the new generation is more likely people of color. If they don’t get to know each other, they are less likely to support each other.”