The late, great comic Robin Williams once opined that there is nothing quite as boring as whale shit. Dull or not, this unsung substance may be key to solving our climate crisis. Researchers believe rebuilding populations of great whales could significantly increase the vast amount of atmospheric carbon absorbed by tiny marine algae called phytoplankton, which rely on nutrients from the leviathans’ fecal plumes.

Though scientists have long known about phytoplankton’s importance to climate stability, the counterintuitive connection between whales and the climate has failed to gain mainstream traction — until now. A chance encounter on the high seas between marine researchers and an IMF economist has produced an unorthodox calculation that’s attracting the interest of investors: $2 million per whale.

Dr. Ralph Chami is not an expert on marine mammals. An assistant director at the International Monetary Fund, his day job focuses mainly on working with fragile states in Africa and the Middle East. But in 2018, he tagged along on a scientific survey of blue whales off the coast of Baja, Mexico with Michael Fishbach of the Great Whale Conservancy and other researchers from around the world.

Long days on the water were followed by evenings of shoptalk over beers and dinner, during which Chami was introduced to jargon like “whale carbon” and the “whale pump” — phrases that describe how these marine mammals help remove huge amounts of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

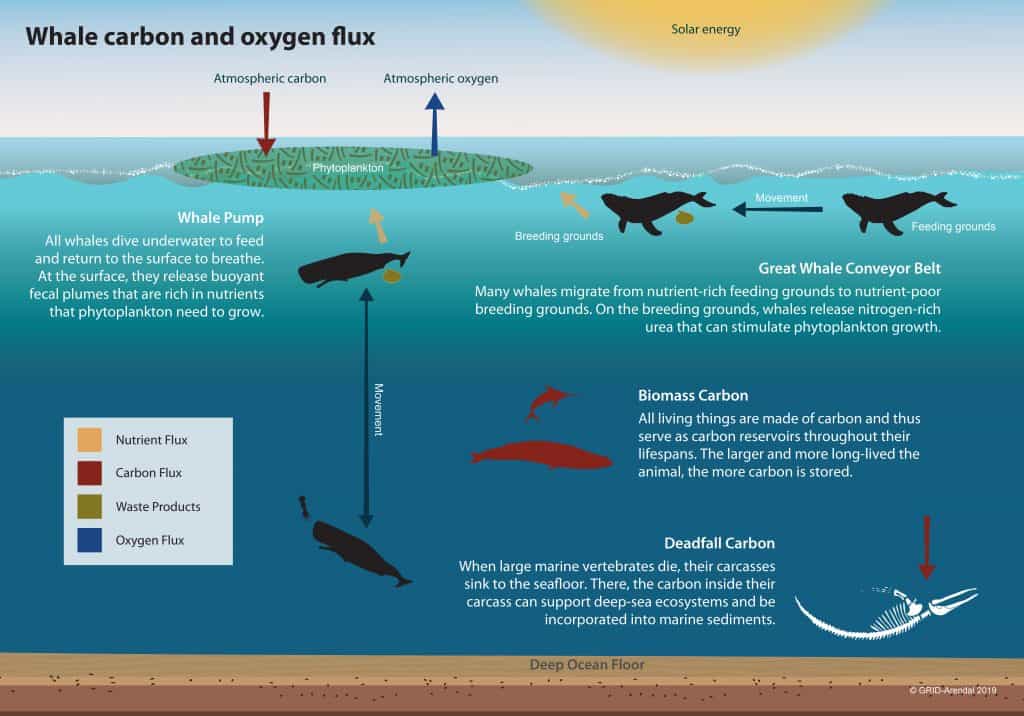

The largest animal that has ever lived, blue whales can grow up to 100 feet long and weigh over 180 tons. An entire African elephant could fit inside the mouth of these giants. Like all living things, whales accumulate carbon in their bodies as they grow, and because they typically sink when they die, they take all that carbon with them to their watery graves. Upon its demise, the average whale can carry the equivalent of 1,500 trees worth of carbon to the bottom of the ocean and out of atmospheric circulation for centuries.

It is while they’re alive, however, that whales play a more active role in fighting climate change. Feasting on shrimp-like krill at depth, they release fecal plumes rich in nitrogen and iron when they surface to breathe. In delivering these deep ocean nutrients to the sunlit surface, they encourage the growth of phytoplankton, the microscopic algae that are truly the lungs of the planet. This process is called the whale pump.

Phytoplankton capture about 40 percent of the world’s carbon emissions and produce half of all atmospheric oxygen — the equivalent of four Amazon rainforests. Every second breath you take is provided by these tiny marine plants. They are also the primary food supply of krill, so whales are helping to feed their own food supply by providing the nutrients that nourish them. Scientists believe this is why whales do their bathroom business within phytoplankton blooms, helping to maximize the biological benefit to themselves.

What is a whale worth?

Aboard the research vessel, Chami knew he wasn’t much help to his crewmates in their studies of whale behavior. As an economist, his expertise lies in linking monetary values to real-world outcomes. It was during the voyage, however, that he had an epiphany: He realized how economics could help solve the problem of turning an esoteric concept like the whale pump into tangible action to fight climate change.

“Maybe I can help you guys,” Chami told the scientists. “The problem is that the language you speak is not the language the money guys speak.” Back in his office, he started assigning dollar values to the benefits whales provide the planet.

What he discovered would make any investor buy stock in whales. An average whale in its lifetime will store the equivalent of 32 tons of carbon dioxide in its body. Factoring in enhanced carbon capture by phytoplankton from fecal fertilizing, as well as improving local fish stocks and ecotourism, Chami calculated that great whales are worth at least $2 million each. Multiplied by all the filter-feeding whales on the planet, that means these marine giants provide over $1 trillion in economic value around the world.

In December, he published his findings in an IMF publication, sparking renewed interest in whale conservation that is now reaching an influential audience in the finance world. Chami and Fishbach recently returned from the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. After finishing their presentation to a room filled with global bankers and investors, “We were mobbed,” he says.

Based on the response his research has received, Chami believes the financial world could play an important role in contributing to whale conservation. Now that Chami and his collaborators have put hard numbers on the ecosystem services provided by these marine giants, economists could craft market-based pricing mechanisms so that whales could, in effect, fund their own recovery efforts.

Saving the whales so they can save us

Many whale populations are now bouncing back from the edge of extinction. While this is a conservation success story, much more could be done to speed their recovery. Some species like the blue whale are still at only three percent of their historic numbers.

The causes of whale mortality are well known, but addressing them requires changes that will cost countries and companies money. For instance, in spite of an international whaling moratorium signed in 1987, Japan, Norway and Iceland still kill over 1,000 whales per year in commercial or “scientific” hunting (a dubious designation.) However, Chami has revealed that a live whale is worth over 20 times more than a “harvested” one, which has a market value of only about $80,000.

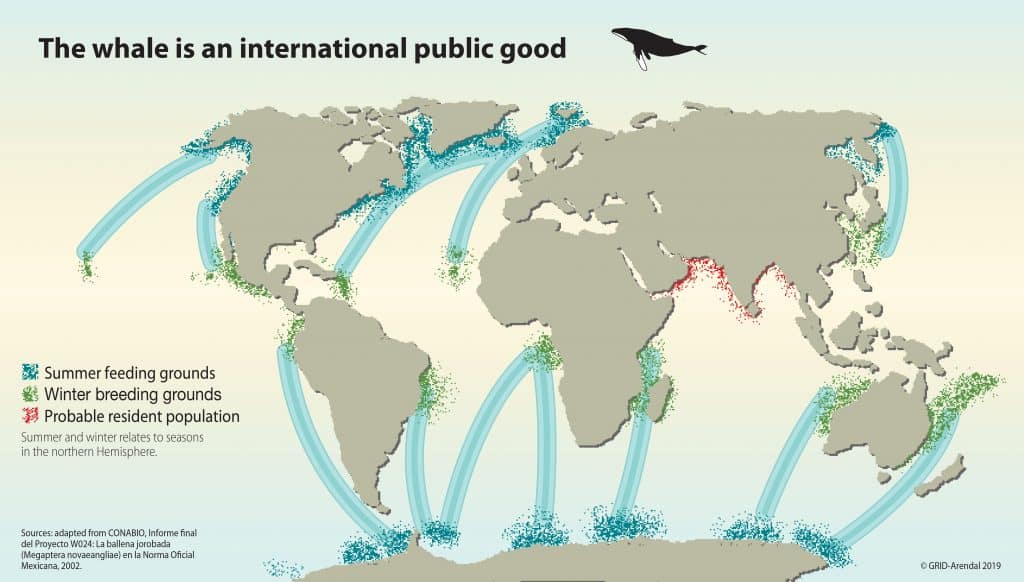

A far larger number are killed by ship strikes, entanglement with fishing gear, marine noise and plastic pollution. Solving these problems will mean shifting commercial shipping routes and slowing vessel speeds in places where whales are likely to be present. Improved fishing gear and better local enforcement will reduce the number of whales caught in floating ropes and nets. Fishbach also flags the need to ban single-use plastics accumulating in the ocean. “These animals can’t swim around in a garbage dump and survive.”

All of which is to say, strategies for boosting whale populations will cut into various entities’ profit margins, which is why it’s important to monetize the value of individual whales. Take ship strikes, for example. Altering busy shipping lanes to avoid seasonal whale migrations has been shown to work in places like Boston Harbor, where slight changes made to navigation routes in 2007 decreased whale and ship encounters by over 65 percent. Such changes aren’t free, but the figures provided by Chami and the co-authors of his study put these trade-offs in perspective. For instance, Maersk is the largest container shipping company in the world, operating 786 vessels that travel to 116 countries. As large as this operation is, operating revenue for Maersk in 2018 was $39 billion — less than four percent of the $1 trillion in climate value provided by the world’s remaining great whales.

Clearly the costs incurred to save whales are worth it from an overall monetary perspective. But who will reimburse companies like Maersk so they’ll change their behavior?

Chami believes framing whale conservation around economic benefits will enlist powerful organizations like the World Bank, the IMF and United Nations to help coordinate recovery efforts or manage a global whale fund. Governments around the world collected $44 billion in carbon pricing in 2018 so, in theory, there is ample money available to direct it where it is most needed. Small island nations like East Timor and the Dominican Republic have globally important populations of whales passing through their waters and could benefit from outside funds to speed their resurgence. Increased whale populations would likewise build ecotourism and the productivity of local fisheries in countries with weaker economies.

Accelerating the recovery of great whales could be considered a “no-tech” type of geoengineering to scale up removing existing CO2 from the atmosphere. It is estimated that increasing phytoplankton populations by only one percent would be the equivalent of adding another two billion mature trees to the planet.

Saving the whales for their own sake is important enough. We are just beginning to recognize that they are also saving us. Putting a price on their services could be a positive way to increase the abundance of these magnificent creatures — and their planet-saving poo.