About ten years ago in Copenhagen, I was riding my bike when I stopped in the middle of the bike lane to check the directions on my phone. Suddenly there was a ringing of bells and shouts and what sounded like curses. I quickly realized I was blocking everyone riding behind me and sheepishly moved to the side. Another time — this might have been in Amsterdam — I heard people shouting behind me. It turned out I was calmly strolling along in the bike lane, once again obstructing traffic.

Of course, as someone who gets around New York on a bike all the time, I feel the same way — annoyed and exasperated — when folks exhibit that kind of behavior here. I don’t shout and curse, but I do ring the bell, and once bought a really loud horn via Kickstarter. It turned out to be too loud. Obnoxious.

Sometimes a bit of social pressure can convince us to change our behavior, but other times, we need what behavioral economists call a “nudge” — a small reward or penalty that convinces us to adapt in some way.

In 2014, Mexico decided to try nudging its citizens to drink fewer sugary drinks. Obesity is a big problem in Mexico — at the time, the rate of diabetes there was one of the highest in the world. So the government placed a 10 percent tax on sugar-sweetened beverages — not a very large amount, when you consider how cheap soda is.

It worked. Since the tax was implemented, there have been two studies of its effect on consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks, and a third on the health and social effects of this behavioral change.

The first study showed a 5.5 percent reduction in the consumption of sugary drinks the first year the tax was in effect. The soft drink industry, no surprise, pushed back, arguing that the reduction could be due to natural sales fluctuations. But the results of a second study published in 2017 showed even further reduction: 9.7 percent.

People in Mexico, it seems, are getting used to drinking fewer sugar-sweetened drinks — enough so that the beverage industry has been forced to shift its stance, now claiming that there’s no proven health benefit to reducing sweet drink consumption. But another, more recent study does exactly that — it projects the health and economic benefits of lower intake of sugary drinks for adults over a 10-year period. Here they are:

189,300 fewer cases of Type 2 diabetes

20,400 fewer strokes and heart attacks

18,900 fewer deaths

$983 million savings for Mexico

Will this work in other countries or cities?

Back when he was mayor, Michael Bloomberg backed a soda tax in New York City. He also tried to ban large-size sugary drinks outright. Neither effort succeeded. So he took his campaign to Philadelphia, which implemented a tax of 1.5 cents per ounce on sweetened drinks in 2017 and sales fell 38 percent. (In reality, sales actually fell 51 percent within city boundaries, but University of Pennsylvania researchers had to adjust the number to reflect all the people who went outside city boundaries to purchase cheaper soda.) The tax revenue goes to parks, pre-kindergarten programs and libraries. Bloomberg also helped fund lobbying that resulted in Berkeley, California instituting a similar tax in 2014 and as a result sales decreased there by 52 percent.

Other cities have implemented taxes on sugary drinks, too, like San Francisco, Seattle and Boulder, Colorado. From the Denver Post:

“When you’re trying to modify behavior, you do two things,” said [Boulder] councilmember Sam Weaver: tax the behavior you don’t want and use the money to encourage behavior you do. The soda tax is a “shining example” of that principle at work, he said.

Other countries are taking similar steps. Some 29 percent of the U.K. population is classified as obese — that’s beyond simply overweight — and a sugary beverage tax went into effect there in April. There has already been an effect. In an attempt to avoid some of this tax, some beverage manufacturers have reduced the amount of sweetener in their drinks. Former Prime Minister Teresa May, a diabetic herself, was initially opposed to such measures, which she saw as anti-business, but ultimately came to embrace the beverage tax.

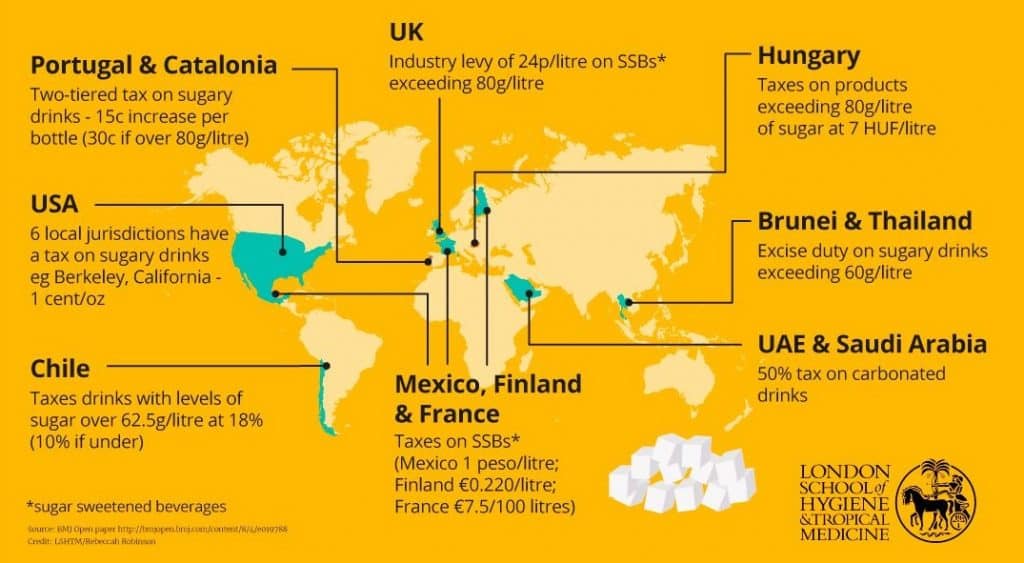

Here is a map of where these policies are going into effect so far:

The health and economic benefits from these taxes in most of these cities and countries has yet to come in, but I think one can assume the results will be similar to those in Mexico. What is a little surprising is that folks are not always turning to other sources for a sugar fix… they are genuinely changing their behavior. While studies have shown some compensating behavior, if people were replacing all that sugar with something else then presumably we wouldn’t be seeing those health benefits.

Are taxes a fair way to change behavior?

I think we can say that this tax at least does what it’s supposed to do: it nudges people away from sugary drinks, which appears to have social and economic benefits for society. One could argue, though, that using money to change behavior targets mainly poor folks whose budgets are tight will thus buy less, while wealthier folks can afford to pay the tax and keep guzzling the drinks if they want to.

That means that alternatives need to be in place, which makes taxing sugary drinks similar to congestion pricing. Congestion pricing isn’t a penalty for coming into the city — it’s a penalty for coming into the city by driving, and driving has a steep cost for everyone. That cost comes in the form of traffic, pollution, and the threat of collisions. That’s why some cities impose a congestion charge: to reflect the actual, hidden cost of driving to society.

Congestion pricing charges can be avoided if public transportation is provided as an alternative. But to be fair, public transport has to be an available (and good) option, and not every city has a good public transport network. With sugary drinks people do exercise their option when they have it — in Mexico they opt for the nearby water or diet sodas, which are not taxed and whose sales went up 12 percent.

Some folks have claimed that taxes like these are not a fair way to change behavior, as they don’t offer folks a choice. These people feel the state does not have the duty or right to force its citizens to make healthier choices. They call this the nanny state, which implies that it treats us like children. But if public transport or healthier drinks are an option — and for this to be fair they must be — then this argument falls apart. Folks do have a choice.

In addition, these taxes and fees tax could help cover the costs to the entire country — the medical repercussions, the missed work — caused by consumption of sugary drinks. Seat belt laws and lower speed limits once got a lot of pushback, too. Sometimes that nanny state is watching out not just for you, but for the other people that you might harm with your choices, and the costs to society that everyone then is forced to pay.

Rousseau called it a social contract. I’m simplifying, but the idea is that we give up some small freedoms for the greater collective benefit. That is what being a social animal is about — and we are social animals, like it or not. It is a prisoner’s dilemma, in a way: if everyone cooperates, everyone gains. If someone decides their own personal freedom is more important, then everyone, including that person, gets less.

Is money always the best incentive?

Although it sure seems to be working in the case of sugary drinks, I’d be careful about assuming a monetary penalty is always the best method for changing behavior.

Take the study “A Fine Is a Price” by Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini, which examined the behaviors of parents whose children attended an Israeli daycare center. The day at this facility ended at 4 p.m. but some parents picked up their kids later than this, forcing the staff to wait around. So the researchers decided to introduce a cash penalty for lateness.

The result: even more lateness.

The explanation given was that we often act out of a sense of fairness. Picking up your kid on time seems like the right thing to do, and parents who were late to do so felt guilty. The introduction of the penalty meant that there was no longer any social pressure to behave cooperatively, and no more sense of guilt if one were late.

People don’t always do things for economically rational reasons and people don’t always behave in the ways that classical economics predicts. Samuel Bowles wrote a whole book on this phenomena called The Moral Economy, making the case that purely economic incentives don’t always lead to predictable behaviors.

The point is that one has to be careful when trying to modify behaviors with a cash penalty. Drinking sugary drinks may feel good, but it is not a public good… and it is not socially cooperative behavior either, unless you’re buying drinks for the whole village. If one can see their behavior as possibly harming others — say, standing in a busy bike lane while looking up directions on one’s phone — then social pressure can sometimes change the behavior without the need for penalties. If folks increasingly gave sugary drinkers the side eye for costing everyone money, then taxes might not be necessary — but we’re not at that point yet.

—

This story is part of a collection called Changing Behavior: Stories about learning to grow in ways that benefit society. Read more here.