Monday afternoon of last week, my friend Bobby texted me that a protest was going to assemble at Grand Army Plaza, on the edge of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, at 6 p.m. I rode out there to discover, to my pleasant surprise, that this was to be a bike “march.” Hundreds of cyclists had converged at the entrance to the park.

We chanted as we rode. Traffic stopped at cross streets, and more often than not motorists honked and waved to salute us. The real surprise came when we reached the Williamsburg Bridge. Some cyclists in the lead blocked the traffic heading into Manhattan, and we swarmed onto the westbound lane and over the bridge. A pretty glorious feeling, I have to say.

My impression is that the police in New York have tempered their initially confrontational approach to the protesters. There were no barricades or cars set up to entrap and enclose marchers. It seemed to me that, slowly, some lessons are being learned. But not everywhere — in Atlanta, Rayshard Brooks was murdered, shot in the back as I write this. In many places, nothing has changed.

We talked (distanced) as we rode. We asked each other: What next? What changes can be instituted? (New York is banning chokeholds.) Are the changes being considered enough? And maybe, most importantly, are there policies that have shown documented success in stopping the killings, combating systemic racism and fostering better relationships between neighborhoods and the police?

The answer is: Yes, there are changes that have been proven to work.

There are two types of policies: Ones that reduce the risk of violence during an encounter between a citizen and the police, and ones that reduce the number and kinds of encounters altogether. I’ll start with what happens during an encounter.

Part 1: Less dangerous interactions

8 Can’t Wait

There’s been a fair bit of buzz about 8 Can’t Wait, a list of eight policing reforms recommended by an organization named Campaign Zero that was formed in 2015 by three activists from St. Louis and nearby Ferguson, Missouri.

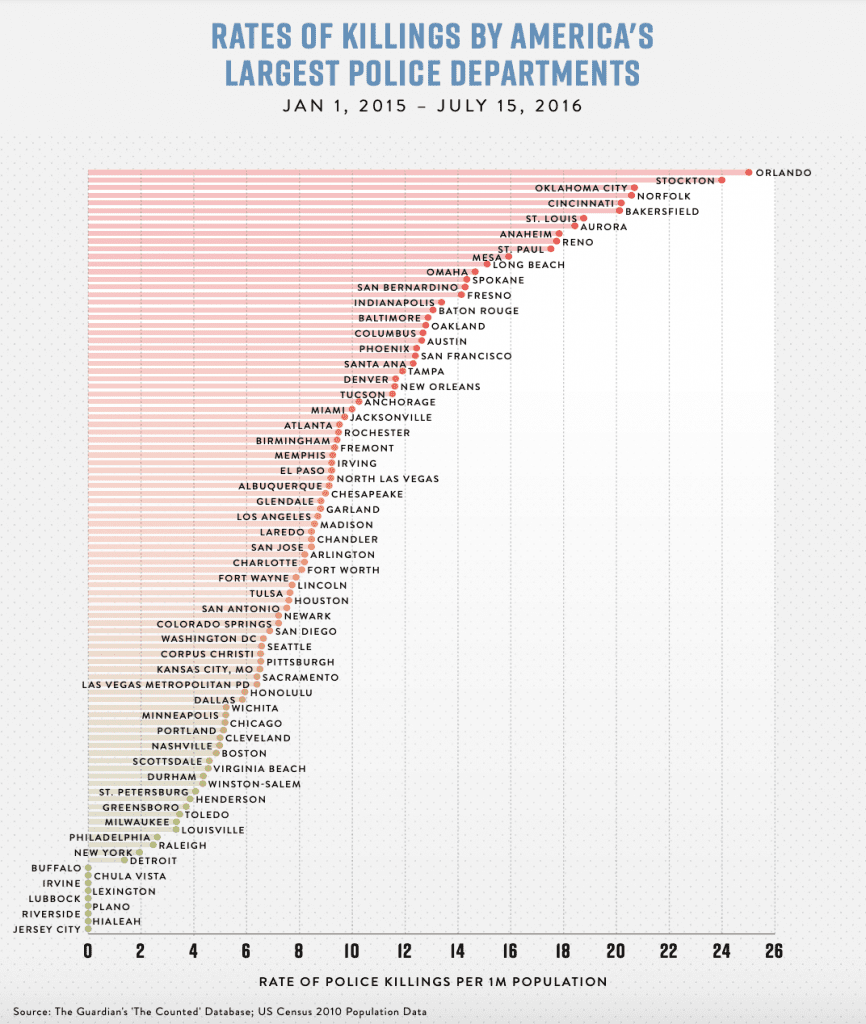

This organization has been name-checked by everyone from Barack Obama to Ariana Grande — deservedly so, as their research is proof of what works and points to a positive way forward. In a nutshell, their data show that cities that have adopted certain policies regulating what happens when police and civilians interact have seen a reduction in killings of said civilians, and that police violence can be reduced by 72 percent if all eight recommendations are adopted!

Since black people are nearly three times more likely to be killed by police than white people, these recommended policies are what we need to adopt — right now. How inspiring that these young people have helped galvanize this push for solutions!

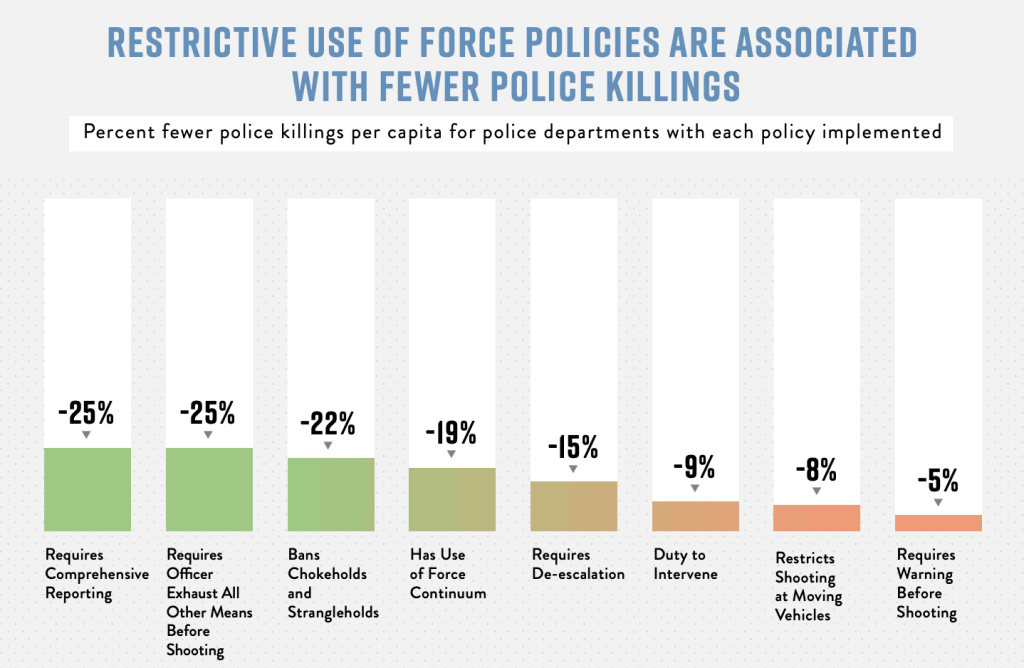

Here are the eight reforms they studied and recommend based on the results of those studies:

- Require comprehensive reporting (every time officers use force or threaten force against someone, they have to report that)

- Exhaust all other means before shootings (unsurprisingly, this can reduce police violence by 25 percent)

- Ban chokeholds and strangleholds

- Require a use-of-force continuum (this limits the weapons or force that can be used depending on the situation)

- Require de-escalation (officers have to communicate with subjects, maintain distance and otherwise defuse tense situations whenever possible)

- Duty to intervene (officers must stop other officers from using excessive force, and report incidents)

- Ban shooting at moving vehicles

- Require warning before shooting

And here is their chart showing the reduction in killings associated with each restriction:

The figures show that there is a clear reduction in killings when each of these policies is adopted. Campaign Zero arrived at these numbers by looking at police department records. The information was not easy to get — the police don’t like to reveal internal data. (Changing that policy is also recommended.) But over the course of a year, by using the Freedom of Information Act and even sometimes resorting to lawsuits, they got the information they needed. This information was then cross-referenced with a database of police killings compiled by the Guardian.

Other factors were taken into account for each city: the number of arrests made, the size of the police force, demographics and the degree of inequality. That’s a lot of stuff to factor in, but if they hadn’t folks might not take these findings seriously.

The good news — and boy do we need some of that now — is that cities where these policies have been applied have shown a significant reduction in killings of civilians. Here is a solution that works, we have proof, and were it more widely adopted we might find ourselves in a better place.

Camden serves as a case study

Camden, New Jersey has adopted some strategies that resemble Campaign Zero’s recommendations. More radically, in 2012 the city disbanded its entire police department. It was then reconstituted with new officers (though 100 of the old ones were kept) as part of a new public-safety force focused on rebuilding trust between communities and the police.

Camden’s chief of police told Citylab that he wants his new officers to “identify more with being in the Peace Corps than being in the Special Forces.” This means using handcuffs and guns only as a last resort, mentoring local youth and generally acting like members of the community. For instance, every new recruit in Camden now starts out by knocking on doors in the neighborhood they’re assigned to, introducing themselves to the residents and asking them about the important issues where they live.

Camden used to be one of the most violent cities in the U.S. Since 2014, however, its crime rate has dropped by half and reports of excessive force by police have dropped by 95 percent! It’s a complicated story — not as simple as it might seem, and more than can be told here — but it shows restructuring can work.

The not so good news is that, according to Campaign Zero, only two large cities — Tucson and San Francisco — have adopted all of the policies 8 Can’t Wait recommends. These reforms often meet resistance despite proof that they work. Police unions work hard to oppose them, claiming they hamstring officers who are simply trying to do their jobs.

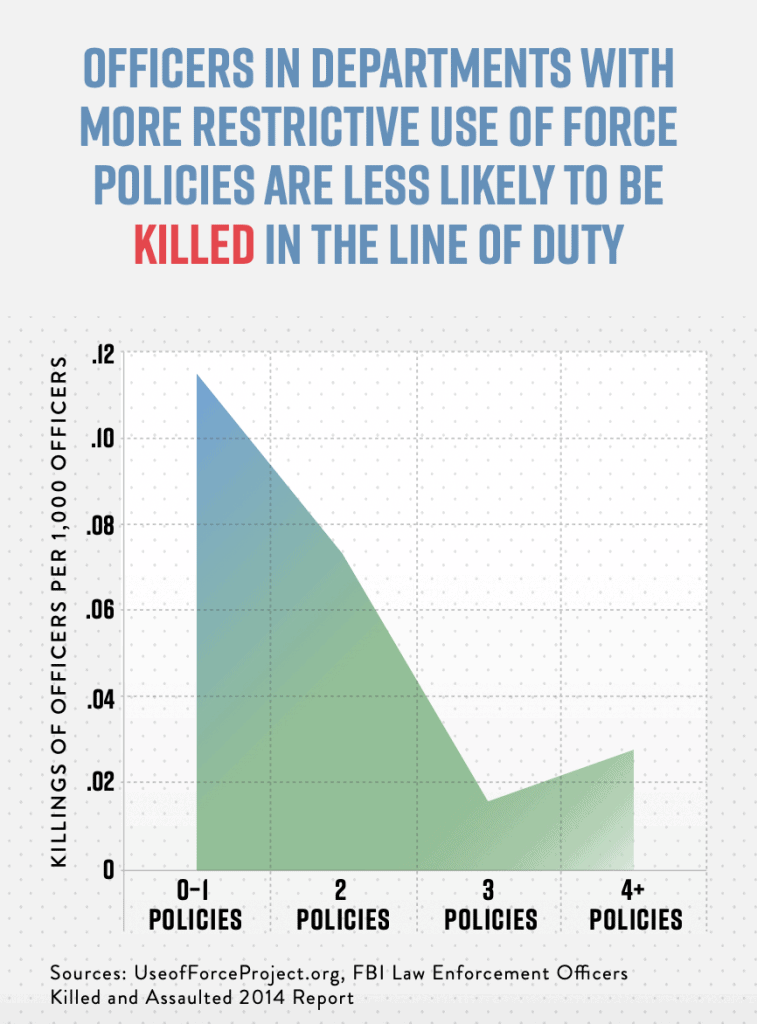

But there is evidence that this argument is false. Many of these reforms, besides saving the lives of civilians, also result in fewer police being assaulted and killed in the line of duty –– a win-win situation.

Here, then, is where both sides may find some agreement!

Part 2: Reducing engagement with police

The reforms recommended above are aimed at reducing risk during encounters between civilians (especially black civilians) and members of the police force. But another way to reduce this risk is to reduce the number of encounters altogether. Those changes may take more time to put into effect, but they can affect the whole ecology, altering the relationship between a police force and the citizens they have sworn to protect.

Ending “broken windows”

The broken windows theory posits that targeting minor infractions like vandalism creates a sense of orderliness and control that deters would-be criminals. But it has been proven a false assumption. As the New Yorker recently put it, “Perceptions of disorder generally have more to do with the racial composition of a neighborhood than with the number of broken windows or amount of graffiti in the area.” In fact, according to one study, “Aggressively enforcing minor legal statutes incites more severe criminal acts.” The policy has, it seems, exactly the opposite effect intended.

Increasing diversity on police forces

Whether more diverse police departments are less violent towards black people is a complicated question. One 2017 study found that more racial diversity on a police force led to fewer black citizens being killed — but only once the force was made up of more than 40 percent black officers.

In fact, until a ratio that at least matches the demographic of the city or county is reached, police forces with just a few black officers were found to kill even more black civilians. The researchers theorized this might be a result of those few black officers trying to show that they weren’t going easy on black civilians. There’s a tipping point, and until you reach it, the beneficial effect doesn’t kick in. A token black man or a woman on the force is not going to do it. But when law enforcement matches the population, then a significant reduction in killings occurs.

The Clinton Crime Bill, a.k.a the Violent Crime Control Act

In 1994, Bill Clinton (and Joe Biden) helped to create the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. This bill expanded the death penalty, introduced minimum mandatory sentencing and put limits on parole. It also provided funding to add 100,000 officers to police forces nationally.

A number of studies have questioned whether these measures actually reduced crime — crime was going down before the law went into effect. But it sure established an adversarial relationship between the police and the black community. States joined in, adding their own mandatory sentencing rules, harsher penalties for adolescents and more arrests for minor drug possession. These policies went a long way toward filling up prisons, even the new ones funded by the Clinton bill.

Other studies have shown that increasing incarceration does nothing to reduce crime. But you can bet that 100,000 additional cops on the street increased police encounters, especially in black neighborhoods, many of which ended in violence. We have proof that fixing many aspects of this law will greatly reduce potentially dangerous encounters.

Redefining police work

There have been calls recently to defund the police. In fact, Campaign Zero has even acknowledged criticism that the 8 Can’t Wait campaign emphasizes reform over defunding.

I’m not going to wade into defunding, not in the literal sense. But removing cops from scenarios that they are neither trained nor equipped to deal with is something even the police themselves endorse. Mental health issues, drug overdoses, traffic, homelessness, sex work — these issues are often better dealt with by social workers (who don’t carry guns) than by police who are not trained for them. Taking those responsibilities away from police and making sure trained folks are there to handle those issues will help.

Challenges: Why reform is so difficult

Though the 8 Can’t Wait recommendations reduce police violence, change has been frustratingly slow. There are reasons for this, and fixing these structural issues will go a long way toward making other changes possible.

Lack of federal oversight: With 18,000 police departments in the U.S., each with its own set of rules, reform is like playing whack-a-mole.

Lack of transparency: Police records are kept secret by statute in many states. It’s hard to reform something if you can’t prove it exists — thank God for cell phone videos.

Qualified immunity: It’s very difficult to sue police officers, which makes it harder to hold them accountable. (That may soon change.)

Optics

In my opinion, what police look like — and what their tactics look like — has a huge effect on the relationship between a government and its citizens, especially citizens of color. When police surround and enclose a peaceful demonstration (known as kettling, like putting a lid on a pot of boiling water) it says, in effect, “We are not your protectors, and we will use force to dominate you.”

The same goes for the visual effect of the gear and outfits. Police and other forces aligned like Star Wars stormtroopers with helmets, masks and weapons at the ready are clearly meant to inspire fear. The optics say to citizens, “You are the enemy and we are an occupying army.”

Some cities have wisely taken a different approach. Police at demonstrations and marches in Camden, Newark and Santa Cruz have shown solidarity with the marchers, joining them in normal street uniforms. In effect, this says, “We are PART of the community that we are here to protect.” It’s the opposite of an attempt to surround and contain.

Connected

I am old enough to remember the protests against what was called the Vietnam War in the U.S. (and what was called the American War in Vietnam). I was in high school, and many of us saw the war as illegal, immoral and illogical. America was bitterly divided. National Guardsmen killed (white) college students in Ohio. I remember when, in 1967, Martin Luther King made a speech about how the war, racial injustice, poverty, workers rights and civil rights are all interconnected: “The bombs in Vietnam explode at home — they destroy the dream and possibility for a decent America.”

Many on his team thought this was a tactical mistake — diluting the message, maybe, or risking alienating some followers or what government support existed. LBJ was supportive of the civil rights movement, but he was pro-Vietnam War. The New York Times wrote that connecting the two was dubious.

But, then as now, King was right. To make progress with law enforcement, one has to look wider — at housing, schools, the health care system and, of course, the courts and prisons. Each one affects the others. The remedies outlined above are essential, but the sickness is widespread. Thankfully there is firm evidence of progress here and there. There are partial and proven solutions. It’s not time to give up.