In 1973, the U.S. Department of Defense started the global positioning system project to enable worldwide geolocation with pinpoint accuracy. The first GPS prototype spacecraft launched in 1978, and the full original constellation of 24 satellites became operational in 1993. At first, just the U.S. military used GPS, but by the end of the 20th century, regular citizens — you and I — had access, too.

In theory, we all became less lost.

There was a sureness about that era — a kind of technological smugness. The Internet, another military brainchild, was piped into our homes via noisy modems. The economy was booming (for some people and not others, but the headlines mostly didn’t bother with that nuance). Our bangs were high and fanned just so by copious amounts of ozone-depleting aerosol. We had Oprah and other “talented tenth” figures to make us feel like things were changing. We had yellow ribbons for a war few really understood. We had The Cosby Show. You see where this is going.

We weren’t actually on course. It just looked that way to a lot of us. Clever technology and media — progress — gave us a false sense of being found.

***

There is a form of navigation that predated GPS called “dead reckoning.” If a ship, for example, found itself unable to take cardinal cues from the stars, the crew would calculate their position by using a previously known point, and advance that position based upon known or estimated speed and distance. It wasn’t perfect, but it helped a lot of people survive on the high seas.

The last few years have been a time of dead reckoning. We’re on high seas: climate change, economic inequality, racism and xenophobia, gun violence, political corruption — we’ve lost celestial direction. Our old constellations are indecipherable, our gods all fallen. Technology won’t save us. Neither will the captains, of industry or otherwise.

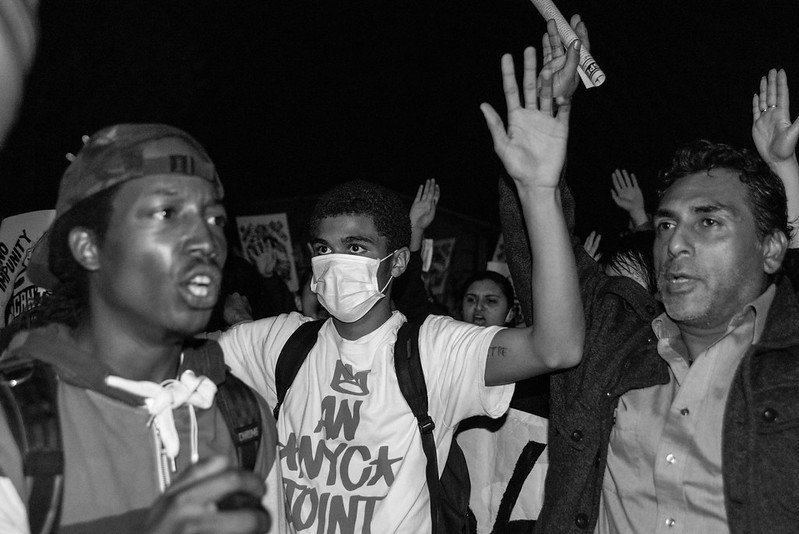

We’ve spent much of the year collectively looking back in order to look forward. The New York Times’ stunning 1619 Project, asking Americans to revise their most precious history. The protests in Hong Kong, demanding the annulment of a bargain struck years ago in which the city-state pretends to exercise democracy and its overseer pretends to let it. The seemingly endless disclosures of women enduring abusive behavior at the hands of powerful men. Children sitting on the steps of government buildings, banding together to say, “You have been reckless with our natural resources. You have turned our borders into battlegrounds. That stops here. We demand a different way.” This is not just backward indictment. This is future-building.

It’s not comfortable — to be lost, to be looking back, to be called out by small children with round faces and watery eyes. In fact, it feels pretty terrible. Even those of us who don’t communicate in 140 characters of vitriol have been called complicit. Rightly so.

But we are less lost now than when we were comfortable. The reckoning has woken so many of us up, stripped away pretense and politeness. It is making us more real. It is allowing us to be honest. To grieve. To move forward with solutions to the problems we’ve created with the urgency they deserve.

And let us be reassured, this is not the first time a reckoning has made us feel terrible and also made us better. Think about young people all over the world who made the late ‘60s uncomfortable for people in institutional power — taking over architecture schools in Rome and administrative buildings in New York, turning the Olympic festivities in Mexico City into political flashpoints, and sparking a mass movement against dictatorship in Pakistan. The streets were filled with protest, family dinner tables erupted in political arguments. It was hard and it was good.

So much was seeded in those years. Every morning I bring my six-year-old to a Title I school in Oakland where every kid is served free breakfast — a direct outgrowth of the work of that era’s Black Panthers. She goes to school with kids from a wide variety of families; she doesn’t blink an eye at two moms, also an outgrowth of the counterculture that began when her grandparents were in their early twenties. She has athletic heroes of all kinds (Title IX) and BPA-free water bottles (Rachel Carson, et al).

The key to being lost is not panicking. And also paying attention to the right people and things. Greta and Charlene are the right people. The right things? Well, I’d argue, “positive deviance” — educators combining neuroscience and cultural competence to not only teach black and brown kids to read, but love learning; the cities with the most effective and dignifying approach to housing the homeless; the courts that are healing, not compounding harm.

One thing you will quickly realize about positive deviants, once you start paying attention to them, is that they aren’t necessarily new. Many of the most effective approaches to social change are old as dirt — loving adults in kids’ lives, solid communities that share knowledge and resources, artists who shift people’s cultural expectations through movies, murals, social media and music. Sure, some problems are best met with a technical solution. But most are cultural and systemic, linked to our accurate understanding of where we are as a society, where we want to be, and how to navigate the gap.

So in that way, as demoralizing and confusing and painful as 2019 has been, I’m heartened that we’re no longer nurturing a collective delusion about limitless environmental resources or a foolproof democracy. We’re recalculating via rudimentary and deeply human systems — our very own broken hearts and our still faithful minds.

Gladys West, a black woman born in 1930, was the mathematician that created the extremely detailed geodetic model of the Earth that became the foundation for the GPS. Her accomplishments were recognized only recently. The Atlantic Black Star reports: “When it comes to traveling, the seasoned mathematician surprisingly prefers a paper map over the tracking system, as some of the data points could be outdated from the time she worked on the equations, her daughter told the newspaper.

To this day, she still does her own calculations.”

In 2020, may we all be more like Gladys.