As megafires ravaged the wilderness of Australia in 2019, Berin Mackenzie got a call.

With less than 24 hours’ notice, the New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment research scientist would be part of a team sent into the path of the blaze to try to save the last remaining stands of the Wollemi pine. The tree with ancient lineage had once covered wide swaths of Australia, but the population had dwindled to fewer than 300.

In that unprecedented moment, as Mackenzie and his colleagues rushed to gear up ahead of a helicopter mission, he says, the responders had some guidance to turn to. Years earlier, a team of experts tasked with the species’ survival had put together a plan for what to do in case the last Wollemi pines were threatened with fire.

Their work was just one part of saving this rare tree, which traces back to the Cretaceous period, earning it the nickname the “dinosaur tree.” The Wollemi was believed to have long since died out when the stand that Mackenzie flew to protect was discovered in 1994 in a remote canyon not far from Sydney. Since then, the conservation team has sent saplings around the world, managed replantings to encourage survival in the wild and carefully guarded the surviving population. While the tree’s story and fame make it a standout among threatened plants, these efforts — including a multi-agency response team and significant public interest — offer insights for protecting other rare species amid the global biodiversity crisis.

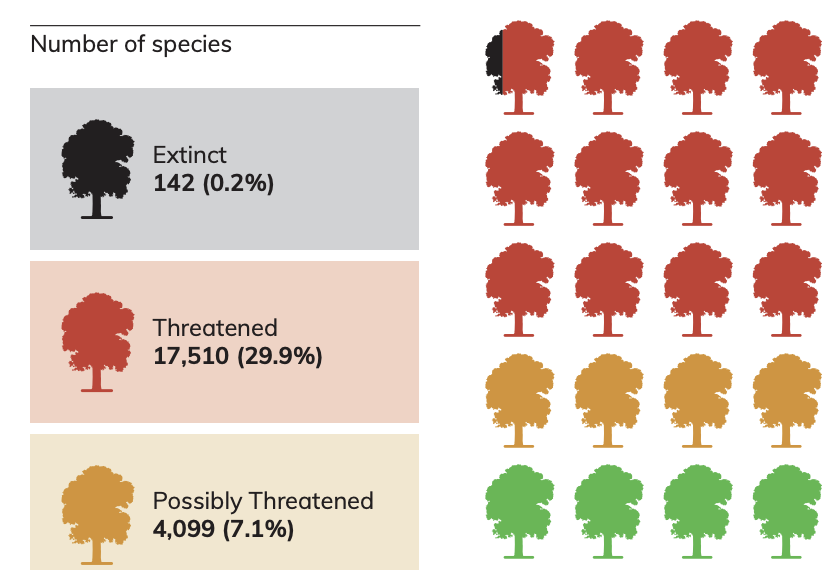

An estimated 40 percent of the world’s flora are at risk of extinction. In Australia alone, more than 1,300 plant species are on the brink of disappearing. Yet plants tend to get less attention and funding than animal conservation efforts.

The Wollemi pine has proven to be the rare plant that rivals the koala in charisma. With its unusual bubbly brown bark and thin leaves that fan fern-like from arcing stalks, the tree has captivated the public. But it’s the tree’s story that has set it apart. Until it was discovered by chance, the Wollemi pine’s line had only previously been known as a fossil.

“There’s no doubt it’s a botanical superstar,” says Cathy Offord, the head of the plant bank at Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan, who has worked with the tree since shortly after its discovery in 1994. “It’s unusual really, to have a plant that’s so well-known and so much loved by the general public.”

Soon after the conifer’s discovery, the Wollemi Pine Recovery Team was formed, bringing together plant conservationists, park rangers, fire management experts and others with a range of expertise to try to secure the species’ survival. Offord’s job was to figure out how to grow the Wollemi pine.

The propagation effort was successful. While seeds from the remaining mature trees were hard to come by, it proved possible to grow from cuttings. After a backup population was established, saplings were sent out to botanic gardens around the world.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Australian National University associate professor Cris Brack helped start a Wollemi pine forest at National Arboretum Canberra, where he observed unusual patterns in how clones grew and died off. He says studying the trees and learning how they grow sheds light on natural history.

“What we seem to have is something from deep history,” he says. “It predates so many of our other plants and animals, and it might be telling us something about life a long time ago.”

The trees’ location in the wild has been kept a carefully guarded secret, to prevent contamination. But the public was invited to participate in a different way: Wollemi pines went on sale, first at auction, and eventually as a backyard ornamental. Saplings were given as Mother’s Day gifts and kept as Christmas trees. Offord herself has a bonsai Wollemi pine at home.

The distribution of cultivated Wollemi pines in backyards and botanic gardens means the species is no longer at risk of disappearing. Having trees spread across the world also serves a scientific purpose, explains Offord, providing insights into how they weather different conditions. She’s been collecting data through a citizen science initiative, “I Spy a Wollemi Pine.”

The learning process with saving the Wollemi pine has been very collaborative — an approach, she says, that has helped in other plant conservation situations. Offord is also involved in a multifaceted response to the spread of the disease myrtle rust, which is threatening 16 Australian rainforest species.

“We’ve used all those skills that we learned from Wollemi pines and some other things along the way, and we’ve brought together those collaborations to apply to trying to stem the loss from myrtle rust,” she says.

With only 48 mature Wollemi pines surviving in nature, experts sought to bolster the species’ chance of continuing to grow in the wild by planting trees in new locations. The effort drew on the expertise of Royal Botanic Garden Sydney senior principal research scientist Maurizio Rossetto, who leads an initiative developing guidelines for replanting Australian species. The project has created best practices for how to reintroduce more than 150 species with genetic diversity that will give them the best chance of lasting survival.

Genetic diversity is key for ensuring long-term success of any replanting project, Rossetto explains. If, for instance, 100 specimens of any species are planted that all originated from the same individual, in the short term, they may look healthy. But eventually, they will flounder and fail to reproduce. Instead, he explains, it’s better to start with fewer specimens from carefully selected plants.

“It’s not about quantity,” says Rossetto. “It is about quality.”

Rossetto’s initiative had already been developing guidelines for other plant restorations when they were asked to take on the Wollemi pine. Initial studies of the Wollemi pine found no genetic variation, but his research identified slight variations in 2016 — a finding that can make new populations planted in the wild more resilient from disease and changing environmental conditions.

That research helped guide a team that planted young Wollemi pines in 2019. Many of those saplings were killed in the same fires that threatened the mature grove, but another replanting effort took place in 2021.

Meanwhile, a central goal, and challenge, remains protecting the remaining Wollemi pines in the wild, says Mackenzie. Some of the trunks in Wollemi National Park are hundreds of years old, but their root systems may date back millennia. Though the genetic diversity can be replicated elsewhere, it’s impossible to recreate the surviving stands.

“That unique set of environmental and ecological events that’s taken place over centuries or millennia to create those stands, that won’t ever be repeated,” he says.

Despite efforts to keep the location secret, a soil pathogen, believed to have been introduced by unauthorized visitors, poses a threat to the trees, according to Mackenzie. Fire remains a concern — while the trees show signs that they can weather fire, another severe blaze before they have time to recover may wipe them out.

The management of the pines during the 2019 fires demonstrated the power of interagency collaboration, Mackenzie says. The work he and others did to save the trees by installing sprinklers, laying down fire retardant and bringing in firefighters to extinguish flames after the front had passed was possible because people in different agencies were aware of the stakes.

“It’s actually set quite an amazing precedent,” Mackenzie says. “That was the first time to my knowledge that resources of that magnitude were put towards protecting biodiversity values in a fire.”

Only one other species had an emergency plan at the time of the fires. There’s been an effort to expand that type of protection since then with the New South Wales government’s creation of the category “assets of intergenerational significance,” which involves drawing up threat management plans for flora, fauna and cultural assets.

In Mackenzie’s view, the Wollemi pine also demonstrates that public engagement is key to plant conservation. The global interest in the Wollemi pine is extraordinary. But getting people invested in species protection can come in many forms, he says, like raising awareness among local communities, and inviting people to help with propagation, or caring for translocation sites. That attention can also bring in more funding, he says: “The conservation programs that I can think of that are most successful have public support and interest.”