From a young age, Alexis Haselberger’s son always asked someone to stick around when he needed to get chores or homework done. At first, she wondered why he needed help.

“Then I realized that he didn’t need me to engage with him, he just needed to know that my body was there,” says Haselberger, a time management and productivity coach in San Francisco.

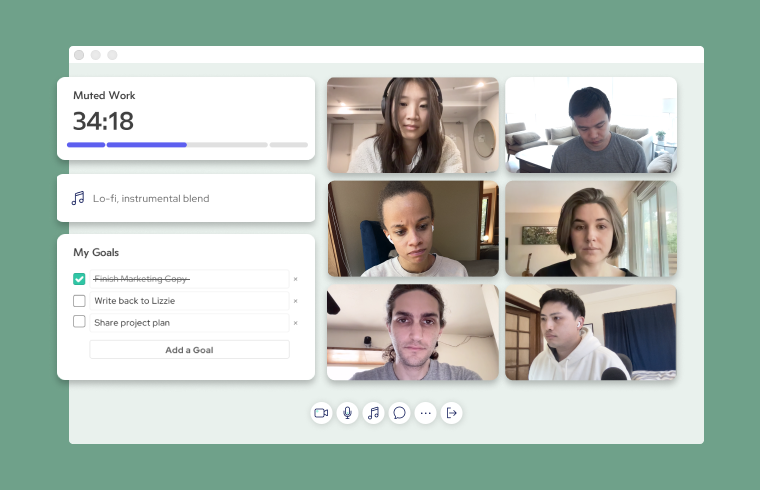

Though they were not initially aware of it, Haselberger and her son were practicing “body doubling,” which involves having someone alongside to help you focus on a task. The term was first coined in the 1990s by a coach specializing in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Haselberger’s now-13-year-old son has not been diagnosed with ADHD, but he continues to find body doubling helpful. So does Haselberger, who does have ADHD. She asks her husband to be around while she completes certain tasks, and she organizes regular video calls with work peers to make progress on “important but not urgent” goals. They start by sharing objectives, then switch off cameras and focus for an hour.

Video calls like these are part of a growing trend: structured online sessions, in groups or in pairs, for anyone who wants to resist distractions and get things done.

In focus

The exact cause of ADHD, which affects an estimated five to eight percent of children globally and often continues into adulthood, is unknown. Among adults, it can create problems with time management, following instructions, and focusing or completing tasks. Although more commonly diagnosed in children, diagnoses are rising rapidly among adults in some countries, particularly among women.

Kirsty Baggs-Morgan, 50, who lives in Malta and runs a business supporting HR professionals, describes herself as “an absolute shocker” for delaying boring tasks until the last minute. For a while, she would ask her assistant to join her on a call when she needed to complete a task, “but we’d end up just chatting for the whole hour.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.That changed with Baggs-Morgan’s ADHD diagnosis in August 2023. A coach recommended Flow Club, a company that hosts “virtual coworking sessions designed to drop you into productive flow.” As in Haselberger’s video calls, participants join a session and share their intentions, then get on with their work until the allotted time is up. In addition to multiple daily sessions, Flow Club users benefit from a supportive community — well over half of users are neurodivergent — and special features to aid focus, such as optional music and the choice of verbal or non-verbal sessions.

Already, Baggs-Morgan has racked up well over 130 Flow Club sessions — often while sitting in a physical coworking space. “For me it’s been an absolute game-changer,” she says. While the physical community provides real-life interaction, the online one helps her to get work done, and even to stick to a regular morning routine. “I like step-by-step instructions. I’ll actually do it because it’s written down,” she says, referring to the to-do list that every participant fills in at the start of a session. Other users might be doing anything from decluttering to writing a book — Baggs-Morgan even recalls someone using a session to take a nap.

Focusmate is similar to Flow Club, but puts users into pairs instead of groups. It was founded in 2016 by Taylor Jacobson, who had long fought procrastination himself. In 2011, he asked to work remotely — “and then I got fired from my job,” he explains, “because I just could not focus.” When he later got into coaching, he discovered the power of virtual coworking, and was convinced it could help millions of others like him.

Focusmate has now hosted over five million sessions, with users in over 150 countries. Like Flow Club, it was not designed with neurodivergence in mind (nor was Jacobson initially aware of the concept of body doubling), although more than a third of current users identify as neurodivergent and about 28 percent have an ADHD diagnosis. And while Focusmate is billed as being for “anyone who wants to get things done,” Jacobson suggests its value is much deeper, as he knows from experience: “When we say procrastination… you’re not living the life you want to live. ‘Procrastination’ sounds kind of trite, but it’s not. It’s really demoralizing and sad.”

Feedback from Focusmate users backs that up, Jacobson says: “It’s insane how life-changing this is for people.” A recent company survey among 212 regular users with ADHD found that their productivity increased by an average of 152 percent. Ninety-eight percent said Focusmate helped them make good use of their time, 82 percent that it helped them feel less lonely and isolated, and 88 percent that it improved their well-being. Flow Club does not have data specific to ADHD users, but co-founder Ricky Yean points to its “exuberant” testimonials and the fact that users attend an average of 10 to 11 sessions weekly.

CEO of the brain

Joining strangers online to get work done has become increasingly common, particularly since the Covid-19 pandemic. Caveday and Flown offer virtual coworking for anyone; other services target particular audiences, like Writers’ Hour or Preacher’s Block. Online “study rooms” for students are also widespread.

But why do they work? Focusmate cites research on the benefit of “precommitment” and social pressure. Yean points out that even brief social interactions unleash dopamine, which drives motivation (dopamine levels can be lower among people with ADHD). Other research finds that we may change behavior when we know we’re being observed, that company can have a calming effect, and that our performance improves when we train alongside others.

For Haselberger, joining a body doubling session provides that small but important push to get started. “We know from the research that action begets motivation, and not the other way around,” she says. “If you are body doubling, then you’re saying, ‘Okay, I’m going to do this thing.’”

Zareen Ali, the London-based co-founder of Cogs, a mental well-being app for neurodiverse people, suggests body doubling is a way of outsourcing the “CEO of the brain” — the part that’s telling you what to do. “Having someone else take on that role acts as an external motivator,” says Ali.

Belonging matters

For neurodivergent people, there’s also the benefit of feeling less judged. Neurodivergent young people still face “a lot of bullying,” notes Ali, who studied educational neuroscience, and they often value peer support.

Kirsty Holden, 37, echoes the importance of finding like-minded people. She is awaiting an ADHD diagnosis, following years of feeling that something wasn’t right. “I grew up not really feeling a part of anything,” she says.

Holden, an online business manager based in Yorkshire, England, was not tempted by platforms like Focusmate or Flow Club, but joined the ADHD Business Collective, a coach-led program that includes body doubling sessions. She values the personal element: “Just knowing that those people get me and know my name… that’s what I really like.”

“For a lot of ADHD-ers, we haven’t felt safe to share what is going on in our minds,” Holden adds. But that is changing. “There are people out there that understand this, there are places where we belong.”

More scaffolding

Online body doubling is unlikely to work for everyone. Neurodiversity is “a massive, umbrella term,” Ali points out, and even people with the same diagnosis may be very different. She herself is autistic and finds body doubling distracting.

One of the barriers highlighted by both Focusmate and Flow Club is apprehension about meeting new people. Asking for a body double might also feel like admitting you need help, says Jacobson. Users of both platforms are majority women; Yean wonders if men find it harder to show some vulnerability.

Things have come a long way since the pandemic-prompted surge of remote working. Tools like Zoom expanded what was possible, but there was a lack of tech to properly support new ways of working, says Yean. People were “burning out like crazy” as they struggled with more responsibilities than ever and blurred boundaries between work and personal life.

“We went from ‘we can’t’ to ‘we can,’ but that’s such a low bar!” says Yean. “Are we thriving? Are we happy? … And are we able to manage all this?”

Flow Club — which aims to create a space of positivity and friendliness — is “in our little corner of the internet, which is trying to create a little bit more support, a little bit more scaffolding, a little bit more camaraderie with other people who share your mission or share your goals,” Yean continues. “I think we have learned that there’s ample opportunity to create more of these types of spaces that are much more supportive. And I think you can define ‘supportive’ in so many different ways.”