Three decades ago, when Mira Mahanty arrived as a bride in her husband’s West Bengal village of Jharbagda, she immediately began to worry about the bare, stony hills that surrounded it.

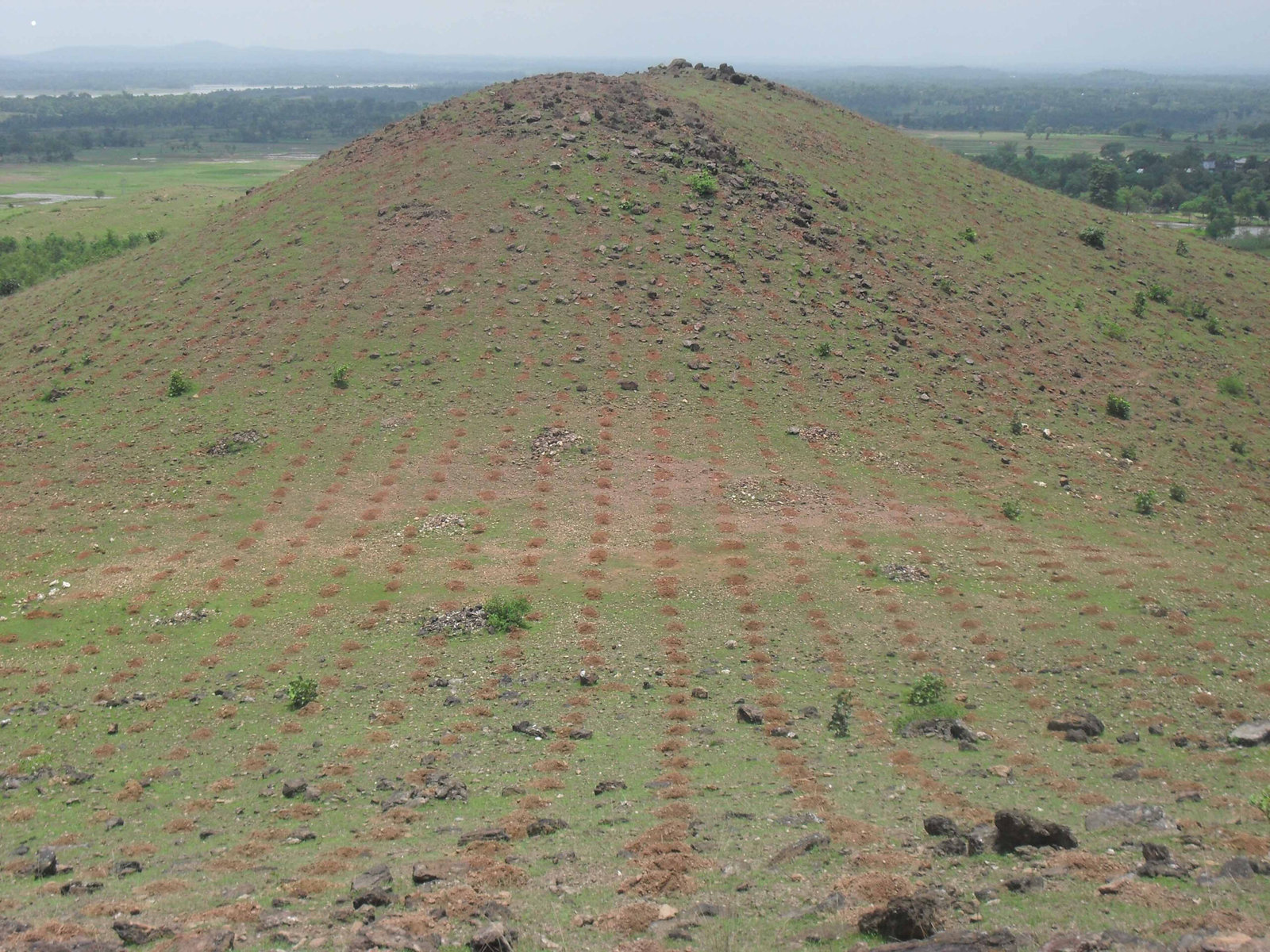

The barren, boulder-covered foothills reflected harsh heat waves at the village all summer long, and during the wet season monsoons sent rainwater tumbling wastefully into the gully below.

“There were a couple of small, thorny bushes here and there, and just one tree on top of the hill,” recalls the 52-year-old mother of three. “Summers were unbearably hot then.” Coming from a family of traditional farmers, Mahanty was appalled to see how the rainwater could not be utilized or stored. She also noticed that the village’s farms were struggling. “It became hard to dig wells,” she says, noting that the region’s water table had plunged by 40 to 50 feet.

Two decades ago, however, the region began staging a dramatic green revival. Propelled by the collective effort of over a hundred villages, the hills surrounding places like Jharbagda are now deeply forested with native trees that provide fruit, mitigate heat waves and contribute to water retention. With some 5,000 acres already reforested, their mission continues to this day.

The reforesting of the area that surrounds Jharbagda shows how even a region denuded for decades can still make a dramatic comeback if certain practices are followed. Learning these practices is of global importance, because while adjacent communities may be the direct beneficiaries, from a climate perspective reviving tropical forests is a global concern.

One tree at a time

The hills around Jharbagda are a part of the Chotanagpur plateau, a mineral-rich expanse shaped by the earth’s tectonic movements and composed of Precambrian rocks that are more than 540 million years old. According to village elders, long ago the region was a lush tapestry of native forests. But over the decades, as industry grew and a timber market developed, one by one the trees were felled by loggers. Gradually, the expanses of green gave way to barren rocks.

The return of forests to the area around Jharbagda began in the early 1990s, says Nandalal Baksi, director of planning and operation for the Tagore Society For Rural Development (TSRD), a pan-Indian nonprofit that works to uplift local communities.

“A group of local villagers approached the TSRD to work out certain livelihood-based community programs and solutions to the water crisis,” recalls Baksi. In response, he floated what seemed like a radical proposal to turn the bare landscape around their villages into lush forests.

“We were skeptical of Baksi’s proposal in the beginning,” says Sunil Manjhi, a local farmer from Jharbagda. “How could forests possibly grow in these desolate, barren tracts?” Nevertheless, Baksi convinced a handful of local villagers to make the effort, promising them daily wages for the plantation work. In 1998 and ‘99, the community leaders of three villages signed an agreement with TSRD to participate in the reforesting effort.

According to Manjhi, the villagers themselves got to decide what they would plant, and opted for native trees with commercial value such as sal, mahogany, mango, jackfruit and custard apple — trees suited to the local climate. “The results began to show as the new green patches started dotting the brown landscape,” says Manjhi, “inspiring more villagers to join us.”

To store rainwater at different elevations so that it doesn’t go to waste as run-off, trenches were dug in different villages based on their topography and soil texture, and small barriers called bunds were created in croplands at the base of the hills.

Today’s restored forests on the hills near Jharbagda hold nearly half a million trees, and the neighboring 125 villages have been covered with an additional seven million trees. “Most importantly, the forests and accumulated rainwater are recharging the underground water table,” says Majhi, who owns land in the foothills where he now grows about 2,200 pounds of rice annually, something he couldn’t always do when the land was less lush a decade ago. Mira is happy, too. She can now easily find the water table with her wells at a depth of about 20 to 30 feet.

A local solution to a global problem

If tropical deforestation were a country, it would be responsible for the equivalent of eight percent of global carbon emissions, making it the third highest emitter after China and the United States. But according to an estimate by World Resources Institute, restoring tropical tree cover can alone provide 23 percent of the climate mitigation stipulated by the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.In this corner of West Bengal, reforestation efforts are contributing to that effort while simultaneously providing a livelihood for those involved. In the village of Rajgram, adjacent to Jharbagda, a collective of 11 farmers who own 12 acres of land planted 2,200 mango trees in 2018. According to the farmers, the orchard, in various stages of fruition, produces three to four commercial varieties of mango, fetching an annual return of about $1,200, which is expected to increase further in the coming years.

“This has become possible due to the forests around, which has not only stopped the erosion of soil, but also improved its fertility and moisture retention capacity,” says Pradip Singha Mahapatra, one of the orchard owners.

Women in the region have found additional income through reforestation, as well, by harvesting resources like wild fruits, vegetables, and sabai grass, which is used for weaving mats. The easy availability of dried leaves and wood littering the forest floor also saves them from previous arduous treks spent looking for firewood.

All in all, the forests have increased the average income of such households by 15 to 20 percent, TSRD’s field research has found.

In a gesture of gratitude and obeisance to these community forests, villagers celebrate a unique festival of tying “cords of love” around trees and pledging to protect them from felling. “The school children are particularly enthusiastic about practicing such rituals,” says Amitava Misra, head teacher at Gobindpur Primary School, near Jharbagda village. “The participation of future generations conveys the awareness of safeguarding their native trees in the local villages.”

Meanwhile, watching the evergreen forests revive his native land makes 95-year-old Haripada Mahanty recall the days when he would enjoy getting lost in the erstwhile forests. “I felt sorry to see how the trees disappeared gradually, being felled by the loggers, turning the hillocks bald and barren,” he says.

Today, the nonagenarian is thrilled to get back the forests of his childhood, teeming with birds, butterflies, wild boar, jackals and rabbits. He says herds of elephant have begun visiting these forests from the nearby Dalma Wildlife Sanctuary. They stay for a few days, drinking water from the forest ponds and thriving on fruit trees. The lush green canopy surrounding his village has also cooled it considerably. “There is a pleasant breeze throughout the day as we sit under the trees to enjoy the company of nature,” he says.

The Government of West Bengal began scaling up the program in 2017. According to Manoj Kumar Pahari, a senior state government official, over $7 million in projects are now being implemented across 450 villages to re-green fallow lands, conserve water and promote job creation in local communities. As of July 2023 two phases of the project had been completed, with 6,000 acres of total land re-greened with about 66 species of commercial varieties of trees. The project has benefitted 12,000 households through asset and livelihood creation, says Pahari, and senior government officials from the neighboring states of Jharkhand and Chattisgarh visited the sites in 2022 to learn how to replicate the practices.

“The idea is not just to mitigate climate impacts ecologically, but also cater to the economic crises that the global problem brings,” says Pahari.