On rainy early spring nights, when temperatures reach the mid-40s, Sarah Wilson can be found walking along one of the quiet roads of rural Nelson, New Hampshire.

Sporting a reflective vest over her red raincoat, she sweeps her powerful flashlight from the wooded bank on one side to the marsh on the other, watching for amphibians on their annual migration from winter hibernation hideouts to breeding ponds. When she sees a hopping spring peeper, she scoops the frog up mid-air. When she spies something stick-like, often a slow-moving spotted salamander, she gently picks it up.

Her goal: to help the critters cross the road.

On busy migration nights, just a few cars are a potential threat to the long-term survival of amphibian populations. One study found that spotted salamanders in Massachusetts could face local extinction if more than 10 percent were squashed by cars. Other research showed that California newts at one key road crossing had a mortality rate of nearly 40 percent.

That’s why volunteers like Wilson fan out to help the little creatures navigate one of the riskiest parts of their journey from winter sleep to spring spawning sites.

“Some of these populations are kind of small, and some of the ponds have a population of 100 adults and you have a group of people that devote their cold, rainy nights … to having some of them across the road, then it’s having an effect,” says University of Connecticut professor of ecology and evolutionary biology Mark Urban.

Grassroots crossing initiatives have spread across the US in the last two decades, with volunteers shepherding tens of thousands of amphibians and contributing to bigger local conservation actions. Migration data they’ve collected have influenced policy decisions about everything from land development to infrastructure planning. Communities are closing roads to cars on busy migration nights and building tunnels — and the pandemic provided proof that infrastructure interventions make a difference. A study in Maine found that during spring 2020, when traffic was sharply reduced due to Covid-19 lockdowns, the number of dead frogs found on the road declined by 50 percent.

When frogs and salamanders wake from winter hibernation in woodlands, one of the first things they do is head toward breeding ponds, often the same ones where they were born.

The right combination of rising temperatures and wet weather can trigger what biologists and amphibian enthusiasts call a “big night,” when a variety of species make the pilgrimage simultaneously in large numbers. Spring migration to the ponds and back to the forest is the riskiest time of year for the tiny travelers. Already facing dangers from predators and sudden weather changes, like flash freezes, their journeys are much more treacherous if a route intersects with a road. Sometimes the animals are out in such large quantities that it’s almost impossible for even the most careful drivers to avoid them.

“If you go out after a big night and look along the roads it’s pretty sad,” Urban says. “Even small rural roads, you’ll see so many of them.”

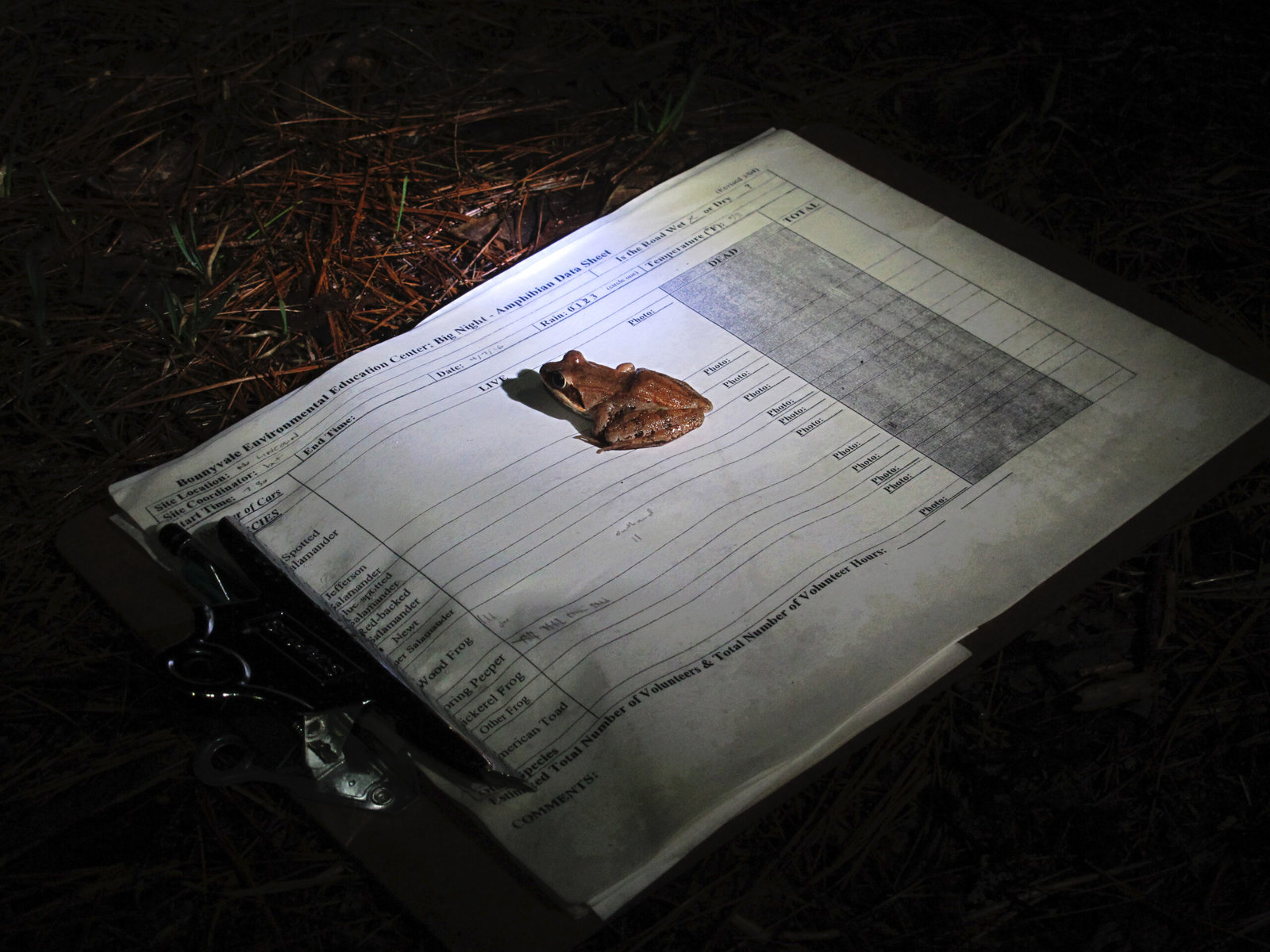

Crossing initiatives try to prevent that gruesome scene, and many also document migratory habits and survival rates for conservation purposes. Some cover large areas, like Maine Big Night, which monitors 300 sites statewide. In the Bay Area, volunteers carry, and keep count of killed, Pacific newts. Wyoming volunteers assist the tiger salamander, the state amphibian. An Oregon “frog taxi” shuttles red-legged frogs across roads and railway tracks.

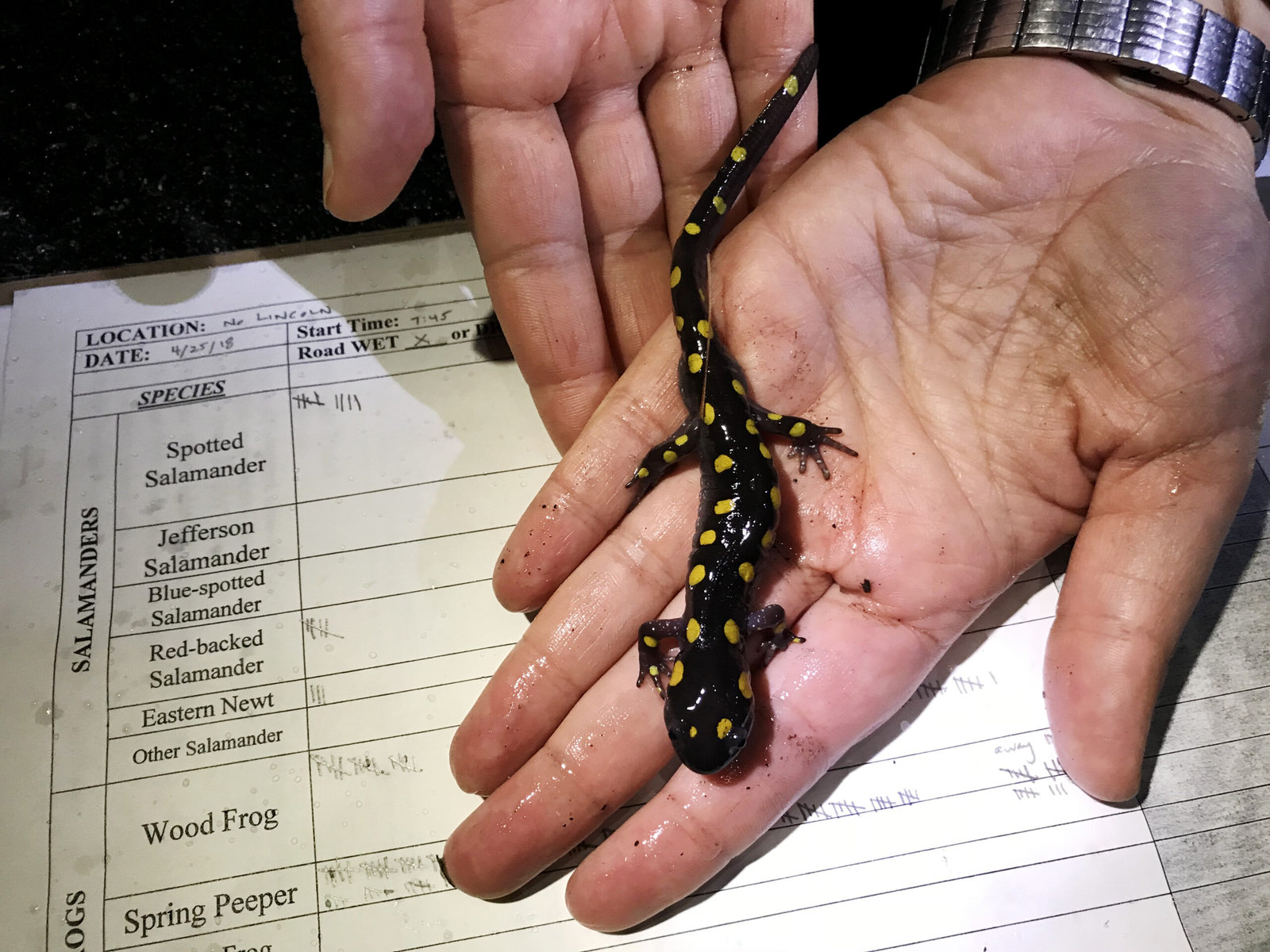

In New Hampshire, volunteers with the Harris Center for Conservation Education salamander crossing brigades collect data on the species they carry and those killed. Wood frogs and spring peepers are common. Jefferson salamanders make rare appearances. Wilson particularly enjoys encountering spotted salamanders. Up to about seven inches long, with dark gray bodies patterned with yellow polka dots, the salamanders live most of the year underground.

“You just have this opportunity to be with a creature that you can’t see pretty much any other time of the year,” says Wilson, who first started helping with the brigades 17 years ago.

Even on the rural road Wilson patrols, where few vehicles pass at night, she sees her efforts as helping the local ecosystem.

Once, as she heard a car approaching from a distance, she scanned her flashlight and saw about 15 salamanders, an unusually high number, in the road. She raced to pick them up, and successfully moved them and herself out of harm’s way in time.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Since 2007, Harris Center volunteers have carried more than 70,000 amphibians. The center coordinates 11 “well-established” sites, known hot spots where volunteers have been collecting data for more than decade. Other sites have been added by locals as interest spread. According to Brett Amy Thelen, who coordinates the salamander crossing brigades across southwest New Hampshire, there are now about 40 sites that report data to the Harris Center each year, encompassing efforts of between 200 and 300 volunteers.

For organizers, Thelen says one of the biggest challenges is predicting when amphibians will emerge. From mid-March through April, Thelen watches multiple weather platforms for the right combination of temperatures and precipitation, but conditions and timing can vary even between nearby spots. Usually each year there are a couple “big nights,” she says, as well as a few with slower amphibian traffic.

Safety is a major concern, because the events require people to be on the road in the dark. The Harris Center posts “Caution Salamander Crossing” signs to alert drivers. Volunteers are directed to wear reflective vests and carry flashlights.

For the amphibians, being picked up is likely stressful, Thelen acknowledges, but less damaging than a car tire. As long as volunteers keep encounters brief, and avoid having anything on their hands like lotion, bug spray or hand sanitizer, the crossings don’t seem to harm the animals, she says.

Over the years, volunteers involved with crossing efforts in different communities have amassed a cache of data, sometimes collected by local conservation groups or logged on the app iNaturalist. While citizen science data has limitations, Thelen says it can help inform local conservation decisions, like when a parcel of land adjacent to an amphibian crossing site in Keene, New Hampshire was under review for development in 2008. Thelen shared data with the conservation commission, showing that in four hours, 25 volunteers moved 838 frogs across the street toward the area under consideration for a housing development. She believes the specificity of the data helped the commission decide against the development and conserve the land, in part because it is a migratory amphibian corridor.

The numbers of amphibians recorded at that same location prompted the city to shut North Lincoln Street to traffic on big migration nights in 2018. In 2022, a second road was closed to through traffic.

Thelen sees crossing brigades as a first step to protect amphibian populations from traffic. Ultimately, they can be part of a longer term strategy, which can involve road closures or installation of wildlife passages under roads.

“I see them as part of the patchwork but not the end goal,” she says. “You can’t carry every frog across every road.”

In Waterloo, New Jersey, volunteers helped between 1,000 and 2,500 amphibians across a particular street for years, according to Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey biologist Christine Healy, who coordinates the amphibian crossing.

Healy’s predecessor was able to make the case based on those numbers that there was a need to build a passage under the road to allow amphibians to migrate with lower risk of becoming roadkill. Four tunnels, as well as fencing that will direct critters toward the passage, are expected to be built later this year.

Healy says the volunteer-run crossing effort was key for building momentum, putting the issue on the radar for local officials and neighbors.

“With a larger number of community members that are in support of this, of course, that pushes forward the idea faster than if it was a problem that people weren’t aware of,” Healy says.

The federal infrastructure package passed last year includes $350 million for wildlife crossings, which many amphibian advocates, including Healy, hope will go toward passages for frogs and salamanders.

Once the tunnel is constructed the organization will shift its volunteer attention to the other two spots they monitor in northern New Jersey. She has a pool of over 100 trained volunteers, and trains dozens more every year.

“We’re not working in nice conditions. We’re out on the roads, when it’s 45 degrees out and it’s raining and it’s dark and there’s a lot of traffic, but people love it,” she says. “Once you’ve seen it once, I feel like these animals kind of just occupy a place in your heart.”