Welcome back to The Fixer, our weekly briefing of solutions reported elsewhere. This week: a San Francisco program buys up real estate to keep people in their homes. Plus, open data helps reduce opioid deaths in Pennsylvania, and a sandy support for a Dutch dyke shows promise.

Time to buy

San Francisco has a displacement problem, and it’s only getting worse. Soaring housing prices have landlords selling their buildings, leaving tenants at the mercy of the next owner. Attempts to slow the surge have been mostly futile, so one program is working within the system to buy buildings at market rates and allow the tenants to stay put.

The city-run program, called Small Sites, funnels public money to housing non-profits. The non-profits then purchase buildings on behalf of the city and, as the new owners, keep the rents reasonable. Much of the money comes from the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, which has used Small Sites to buy 35 buildings, keeping more than 500 residents in place.

Launched five years ago, Small Sites started out with just $3 million, which doesn’t buy much in the sizzling-hot Bay Area real estate market. Now, however, a bond measure is set to put $30 million into the program. To make sure it can be spent right, in June the city enacted the Community Opportunity to Purchase Act, which gives the non-profits five days to purchase any available property before other investors swoop in. “We essentially pay what you pay on the private market for it,” said the director of one non-profit. “We’re not paying any less than another buyer would be paying.”

Release the data!

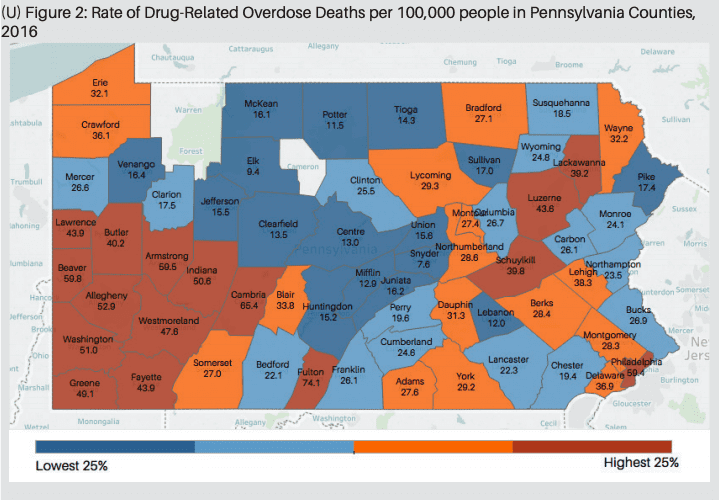

Pennsylvania’s opioid epidemic has been, by many measures, worse than the U.S. national average, with an overdose death rate of 18.5 per 100,000, compared to 13.3 nationwide. But the situation is improving, thanks in part to a digital dashboard that gathers data from across state agencies and makes it easier to read.

The opioid data dashboard is a legible, comprehensive snapshot of the state’s opioid struggles at any given moment, and anyone is welcome to use it. Data include everything from birth complications caused by opioid use, to ER visits caused by opioids, to the number of naloxone treatments administered by paramedics. The dashboard also calculates and creates visualizations of the impacts of opioids on the state’s economy, hospital network, justice system and other vital functions. “Having the command center and the governor’s focus on opioids is a real reason why we’re able to de-silo all of this data and bring things together,” an advisor to the state Secretary of Health told GovTech.

Along with better access to naloxone and closer monitoring of prescription drugs, the dashboard is being credited with Pennsylvania’s 18 percent reduction in opioid-related deaths. The success echoes other states’ efforts, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, both of which have also seen a decline in overdose deaths since allowing agencies to more easily share information.

Nature’s breakwater

The Netherlands was an early adopter of flood mitigation. After a storm surge in 1953 killed 1,800 people, the country built a series of dykes to prevent a catastrophic repeat. One of them, built in the 1960s and ‘70s, is beginning to deteriorate. Normally, such a structure would be reinforced with boulders, something the low-lying country doesn’t have too many of. So instead, the Dutch pioneered a new construction method using a decidedly less stable material: sand.

In 2017, the Netherlands began pumping sand from beneath the Markermeer, the country’s large sea-fed lake, and using it to reinforce the dyke. It’s the first time sand has been used to support such a structure, and so far the nearly 10 million cubic meters of the stuff seems to be holding as intended. The water’s currents and waves are beginning to disperse the sand along the dyke, creating something akin to a natural barrier that might have been created by sea itself.

Now that it’s showing success, the process is expected to be adopted by other countries. “We’ve learnt some generic rules in this project about how to work in a lake system building with nature,” a spokesman for the project told Agence-France Presse, adding that the newly reinforced levee is built to withstand a 10,000-year storm. In addition to flood protection, all the new mud will create a flat surface upon which a nature preserve will be built.