It is a hot, dusty morning in Tilonia, a tiny village in the Indian state of Rajasthan. Under a brilliant pink flowering bougainvillea, a 77-year-old stands, a little tired, a little old, but resolutely barefoot. This is Sanjit ‘Bunker’ Roy, the three-time Indian national squash champion who devised a social experiment in 1972 to address issues that plagued rural India at the time — poverty, illiteracy, disempowerment and gender inequality. His experiment, half a century down the line, is known as Barefoot College, a non-formal learning center which leverages the natural acumen and ingenuity of illiterate villagers to transform them into barefoot entrepreneurs, nutritionists, engineers and even doctors.

“It is a myth that just because you can read or write, you are educated,” says Roy. Wearing his trademark kurta pajama and bearing a gentle, scholarly air, he is an unlikely heretic. But fifty years ago, when he established the Social Work and Research Centre (SWRC) in Tilonia, about 90 kilometers from Jaipur, Rajasthan, the idea that the complexities of engineering, architecture, even medicine could be taught through practice — and not necessarily in academic institutions — was as radical as it is today.

“They asked me, ‘How can you say schooling isn’t necessary?’ I told them our schools and universities were churning out mechanical engineers who’d never held a spanner in their hands and graduates with no understanding of how things work in India.” Instead, he established SWRC, a practical-training approach to demystify and democratize technology and education for the rural poor and develop social entrepreneurs to enrich and sustain in situ markets and institutions.

It was an idea so audacious that even Roy’s mother thought it would crash and burn. But it did not.

Today, the Barefoot College philosophy — that practically anyone can learn whatever they set their hearts on if given the right environment — is embodied in Asha Devi, a sanitation worker belonging to the bottom of India’s caste hierarchy. “I’m illiterate, but learning new things every day!” she says. She is presently learning to unhook intravenous tubes as she trains as a paramedic.

Going barefoot

On an uncharacteristically wet spring morning, we walk through the SWRC campus in Tilonia, a mass of stone buildings, rainwater harvesting structures and geodesic domes that stay cool in the Thar Desert’s hot summer — all built by barefoot architects. Our guide Brijesh Gupta, who has been with Barefoot College since 1982, talks about how excluded he felt by the societal value placed on mainstream education.

“It was hard for me to find jobs as a school dropout,” he recalls. “I’d begun to think that I was less than capable of doing anything but manual jobs.” This changed when he joined Barefoot College, where he has since been a water tester, office assistant, handicrafts seller, visitor coordinator and more.

“We encourage everyone to try all sorts of things, by making them realize that they’re equal to any task, be it puppetry, communication, handicraft, or even solar engineering,” says Roy, for whom understanding people and one’s milieu are the most important aspects of learning.

Barefoot alumni today happily cock a snook at formal education. “Our learning comes from practice, experimentation and mistakes,” Gupta says. “These are hard to teach in formal schools… Perhaps that’s why our country produces so many graduates who know so little!”

Research in India shows that the learning outcomes in government schools are poor and students are unable to perform as expected. In contrast, Barefoot College’s pedagogy leverages the natural curiosity, intelligence and practical skills of villagers. It has had notable successes, albeit on a smaller scale than large formal institutions.

For example, in order to improve school attendance among communities where children are expected to participate in daytime household activities like animal herding, Barefoot College, in conjunction with the Rajasthan government and National Council of Educational Research and Training, piloted three experimental schools around Tilonia, which employed Barefoot teachers and timed classes to suit the children’s household work schedules. After this substantially reduced dropout rates and increased enrollment, in 1987 the project was formally adopted by the government’s Shiksha Karmi (Education Worker) project, which has facilitated the education of over 200,000 children. The College’s 250 night schools now operate in ten Indian states. They are run by Barefoot teachers, lit by solar-powered lights made in-house, and have enabled over 100,000 out-of-school children to bridge the gap between their age and learning levels.

“They come as grandmothers, they go back as tigers”

Other than the children, the majority of Barefoot College’s denizens are older women, and there is a reason for this. “Young people with degrees from formal institutions rarely want to return to work in the village. The men also seek the city’s greener pastures,” Roy says. “But the women remain and can potentially transform rural life and markets.”

Resplendent in a traditional skirt with a pink scarf covering her hair, Kesar Devi has never been to school, and was a daily wage laborer before she came to Barefoot College in 2009. “I learned different aspects of dentistry here under an Italian doctor for six months, and also trained to administer basic homeopathic and biochemic medicines,” she says. “There aren’t any dentists in my village. Now I teach children how to brush their teeth using this model of the human jaw, and also perform simple dental treatments like cleaning plaque, cavity fillings and tooth extractions…I’ve treated thousands of patients from different parts of the world here.”

Near the health center, a group of barefoot nutritionist entrepreneurs make Super Five, a nutritional supplement with whole wheat, lentils, peanuts, sesame and jaggery. “We developed this because there’s a very high incidence of malnutrition among children and pregnant mothers here,” Kanta Devi, one of the group members, says. The group conducts nutritional awareness workshops in neighboring villages and gives Super Five packets to women and children who need it.

However, it is at SWRC’s solar engineering project, where grannies from across the world learn to wield the soldering iron and work with complicated circuitry, that one truly experiences the Barefoot approach.

Solar Mamas show the light

In a brightly lit workshop, a group of traditionally garbed female sanitation workers learn to make circuits. This is the Barefoot Solar Engineering Training Center, where women from un-electrified villages across the world come for six months of training to install and maintain solar lighting systems and rainwater storage tanks. “Everyone just learns from each other,” trainer Magan Kanwar says, “trainers as much as the students!”

Watching Kanwar explain complex circuitry, it is hard to imagine that she has not even completed primary school. “Whatever I’ve learned has been through seeing, learning and practicing in the 20 years I’ve spent here,” she says. “Today I can install, operate and repair complicated solar systems easily!” She has traveled to several countries, including Senegal, Tanzania and Bhutan to train barefoot solar engineers. “At the airport, people often point curiously at my traditional attire,” she says, “but I ask, what do my clothes have to do with my abilities?”

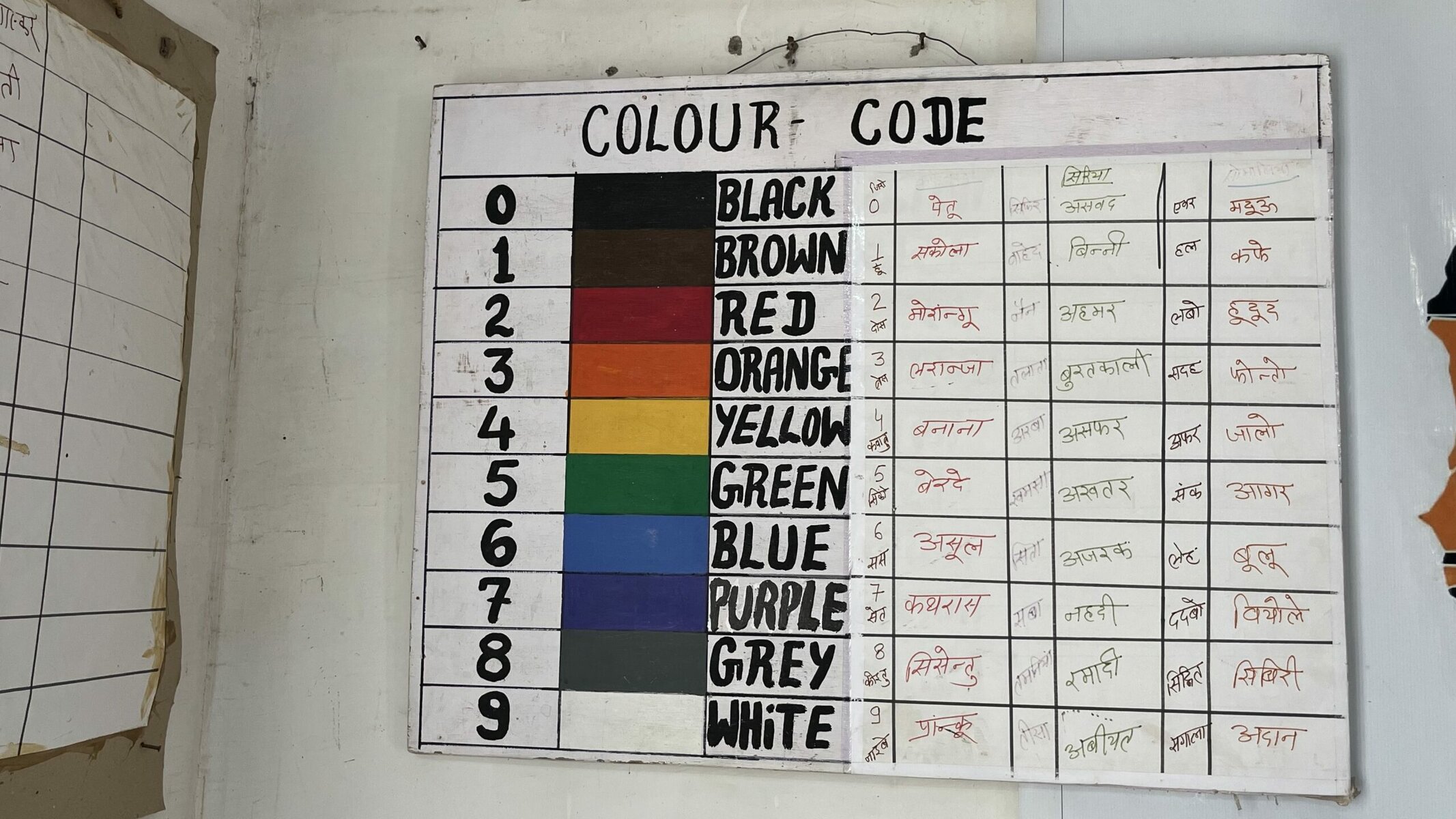

Since 1997, the program has trained over 1,700 women. The International Renewable Energy Agency, which is partnering with Barefoot College to enable women from energy-poor communities to access renewable energy services, estimates that this has resulted in 75,000 houses being electrified, 1,300 villages being fully electrified with solar power and 45 million liters of kerosene pollution avoided. Kanwar has trained women from several countries in Africa and South America, courtesy of India’s External affairs ministry. “Language isn’t a barrier for us,” Kanwar says. “We color code all the tools and circuits to make it simple for everyone to learn.”

“A pedagogy that is able to teach complex circuitry to illiterate villagers in six months is truly remarkable,” says Rama Krishna Reddy Kumitha, author of Social Entrepreneurship and Social Inclusion which resulted from his doctoral dissertation on Barefoot College. He argues in the book that this institution has successfully created the necessary contexts for social inclusion to thrive. “Barefoot College is a radical intervention,” he says. “Over the years, I’ve watched them constantly innovate, constantly explore original ideas and possibilities, and develop new avenues for villagers.”

Spreading across India

In the early ’90s, Barefoot alumni came together under the umbrella of SAMPDA (Society for Activating, Motivating, and Promoting Development Alternatives) to spread the Barefoot ideology and pedagogy across India. Some 22 grassroots organizations, including the Barefoot College, became members, and committed to working in some of the most remote regions across 14 states in India. For example Avani in Kumaon (Uttarakhand state) focuses on rural craft-based livelihoods and renewable energy, while SWRC in Sikkim works on solar energy and rainwater harvesting.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Although Roy’s subversive methodology has, as the Barefoot College website states, impacted the lives of over five million people, not just in India but 96 countries, its potential for further expansion could be limited by certain factors. Kumitha, who has been a Tilonia regular since 2008, says that the “lack of any formal certification, the insistence that all Barefoot trainees must serve in villages only… could feel restrictive in today’s context.”

In his book, he points to a larger threat to the longevity of Barefoot College — a problem that many NGOs with charismatic founders face. “Its second line of leadership is the missing piece of the puzzle,” he says. “Without Bunker [Roy], Barefoot College lacks a visionary leader.” Roy, now 77, says that “finding a young individual willing to work in a village is not easy,” but perhaps the problem lies deeper. In a swiftly corporatizing India, the Gandhian ideals so visible in Roy’s Tilonia might seem a little anachronistic to India’s aspirational middle class youth.

It has not helped that in the last few years, Roy and his cohort have been at odds with a rogue offshoot of Barefoot College — their fundraising arm until they parted ways in 2021, Barefoot International. “Some of our foreign funding has been erroneously routed to Barefoot International instead of coming to Barefoot College Tilonia,” he rues. The conflict has sapped the aging institution of vital energy. In early March 2023, Delhi High Court granted an injunction in favor of Barefoot College forbidding Barefoot College International (BCI) from using “Barefoot College” as part of their company name, their logo or the web domain name www.barefootcollege.org. While this was a victory for Roy, it could take a long time for the institution to recover from confusion.

Oblivious to all this, 6,000 miles away, lights twinkle in a tiny village in Sierra Leone, courtesy of its Solar Mamas who trained in Barefoot College. “When I came to Tilonia 40 years ago, I wondered what us illiterate village women could actually do,” says Kanwar as she helps a trainee to solder some wires. “I’m still learning and doing, doing and learning…”