At Vancouver’s University of British Columbia, the Brock Commons Tallwood House, sheathed in sleek blond wood, stands out among the neighboring gray concrete towers. This striking facade isn’t just an aesthetic choice. When it opened in 2017, the 18-story residence hall was the tallest building constructed of timber in the world. Erected from prefabricated components in just 70 days, it was faster and cheaper to build than a conventional building. What’s more, its material saved over 2,400 metric tons of carbon emissions.

Brock Commons defies a century of high-rise construction norms. Since the dawn of the skyscraper age, cement, concrete and steel have molded our vertical urban realms. But the environmental consequences of these materials has led some in the construction industry back to wood, a material that’s more sustainable and, with each technological leap, an increasingly viable option for large-scale projects.

Proponents of wood construction argue that it is carbon negative, in that it effectively takes CO2 captured by trees and locks it into the buildings it supports. But wood construction has its challenges. Only in the last few years has it begun to come into its own, shepherded by a wave of government incentives, pent-up demand and technological advancements.

New technologies, evolving codes

Construction is one of the world’s most environmentally destructive forces, accounting for nearly 40 percent of global emissions. And the industry’s favorite material, concrete, is perhaps its least sustainable. Concrete’s production causes up to eight percent of global emissions. It also consumes a lot of sand — a disappearing resource — gobbling up 40 to 50 billion tons of it each year.

Reducing reliance on concrete would represent a major climate action victory, but the challenges are formidable: Over the last 30 years, global production of concrete has quadrupled. It is the substrate upon which the world’s urbanization boom is being built. China alone pours more concrete every two years than the United States used in the entire 20th century.

But buildings like Brock Commons point to nascent change in course. Last year, a group of Yale University scientists proposed that wood could largely replace concrete and steel in building construction. In a research paper entitled Buildings as a Global Carbon Sink, they run through various scenarios, the most ambitious of which finds that 90 percent of all new buildings could be constructed of wood by 2050. Doing so, they found, would prevent up to 75 gigatons of CO2 from being released into the atmosphere — twice what the world produces in an entire year by burning coal, oil and gas.

These findings represent what is theoretically possible, not what is likely to happen. But they spotlight wood’s enormous potential to green the construction industry. Matthias Korff, managing director of DeepGreen Development in Hamburg, Germany has been using wood in large-scale buildings for years. For Hamburg’s 2013 International Building Exhibition, he built “the Woodcube,” Europe’s first five-story wood building. It was built entirely without glue or chemicals — the walls are held together with beechwood plugs — and because of its density can withstand a 1,000 degree Celsius fire for over five hours.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Korff speaks passionately of wood construction’s potential to help stabilize the climate. “Every cubic meter of wood that replaces other building materials reduces CO2 emissions in the production of a building by an average of 1.1 [metric] tons,” he says. In addition, says Korff, 0.9 metric tons of CO2 are bound up in the wood, absorbed from the atmosphere by the tree it came from. By this calculation, two metric tons of CO2 are saved per cubic meter of wood used.

Korff is currently planning an eight-story building and a senior citizens’ complex, both made of wood. These will join a growing list of wood construction projects in Hamburg, including an 18-story apartment building and a large housing estate. These projects benefit from the pro-timber construction policies recently adopted by the city — incentives like a 30-cent subsidy per kilogram of wood used in construction. Munich and Freiburg have similar incentives, and Berlin — which will soon break ground on the country’s tallest wood building — recently adjusted its building code to allow large-scale wood structures.

The Era of the Wood Skyscraper Is Arriving

These local incentives build on Germany’s “Charter for Wood 2.0,” which encourages the use of sustainable wood across a range of contexts to help fight climate change. The charter asserts that “consistently using wood as a substitute for energy-intensive materials that have a harmful CO2 impact can make a significant contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

Such policies are key to helping the construction industry transition to more sustainable materials. When Brock Commons was built, British Columbia’s height limit for wood buildings was six stories. (The developer was granted an exemption to the code.) Soon afterward, the 2020 revision to Canada’s National Building Code doubled wood building heights to 12 stories. There’s reason to expect this could lead to a boom in wood construction across the country. Back in 2015, when the code was revised to allow six-story wood buildings, some 500 mid-rise wood buildings were built nationwide.

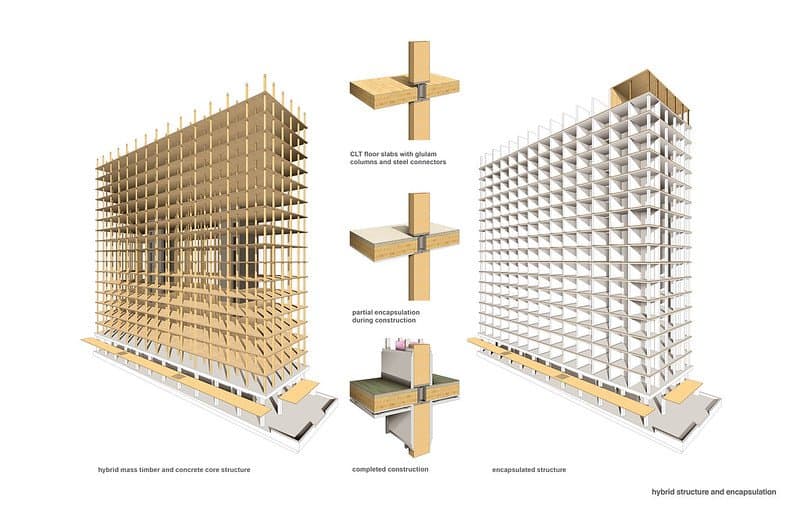

These policy tweaks and the rise in demand that has followed them has sparked the development of a new generation of innovative wood-based construction products, such as cross-laminated timber, panels and beams. Pre-fabricated in factories, these components reduce cost, noise and pollution on construction sites. And the more wood buildings that emerge, the easier the process becomes. When Korff built the Woodcube, for instance, he had to figure out how to make the building fire-resistant and structurally sound because there were no regulations in Germany spelling out how to do so with a tall wood building. Now there are.

Deforestation is not a concern — in Germany, like in Europe in general, the forest stock is growing, and the government is careful about preventing imports of illegal, unsustainable wood. “By 2042, about 78.2 million cubic meters of raw wood will be cut annually,” says Korff. “Only eight percent of this amount would be enough to build the entire volume of new residential construction from solid wood.” Even if 90 percent of all new buildings were constructed from wood, as the Yale researchers posit in their hypothetical, that volume of wood could easily be produced in sustainably managed forests. In Korff’s senior citizens complex, he’s going one step further by incorporating waste wood into the design. “This is deep, deep green development,” he says.