Gerald Koch hurries through a narrow corridor and into his testing laboratory. Inside, employees are squinting through microscopes and peering into screens showing cells and vessels. Part of Hamburg’s Thuenen Institute, the boldly named Center of Competence on the Origin of Timber is in an unassuming brick building in the city’s northeast. Only its garden of trees from around the world hint at what goes on inside — one of Europe’s most sophisticated operations in the fight to stop the illegal wood trade.

“We have already tested large quantities of garden furniture and wooden Easter bunnies,” says Koch. “Now we are expecting the usual flood of wooden toys for Christmas in spring — after all, we test anti-cyclically.”

A global blackmarket

The global wood trade is bigger than ever. Despite our digital age and allegedly paperless society, twice as much wood is harvested and sold worldwide as 50 years ago. This growth in demand has been accompanied by a surge in illegal logging. According to a study by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), 16 to 19 percent of wood imports to the European Union come from illegal sources.

The effects are insidious — deforested jungles, destroyed habitats — and consumers are unknowingly complicit. In 2016, the U.S. flooring giant Lumber Liquidators paid $13 million in fines for selling products made from illegally logged Russian wood.

This is where Koch comes in. He’s seen it all. Fruit knives with fine mahogany handles. A fish sculpture carved from teak. Guitar fingerboards made of protected rosewood. Tables constructed of 20 types of tropical timber — “The Asian manufacturer had declared eucalyptus,” scoffs Koch, for whom spotting phony certificates and forged customs declarations is all in a day’s work.

Since 2013, the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR), similar to America’s 2008 Lacey Act, has banned illegally felled timber from the European market. Customs officers can confiscate it, and carpenters, hardware stores and manufacturers must prove the origin of their timber before selling it. Even private citizens are obliged to make sure their wood is legally sourced — selling grandma’s antique writing desk could be against the law if it was constructed from a species of wood that’s protected today.

The problem is, wood is difficult to distinguish and even harder to source. It’s no easy task even for the scientists at the Center of Competence, which Koch directs. Together with a 15-member team, Koch is responsible for ensuring that timber products imported into Germany and beyond are what they claim to be.

The samples in the lab that day illustrate the enormity of their task: glasses with chipboard crumbs, crushed cardboard coffee cups, colorful bamboo children’s crockery, bags of charcoal and walnut parquet boards — all of it supposedly legally sourced, but is it? Koch takes a cube-sized block of plywood between his thumb and forefinger. “Laminated wood boards contain up to 10 different types of wood, often from the same number of countries,” he says. Before 2013, most of these products would have been sold unchecked. Today, if their origin is questionable, most end up here at the Center of Competence, a critical checkpoint that helps save forests around the world.

Into the woods

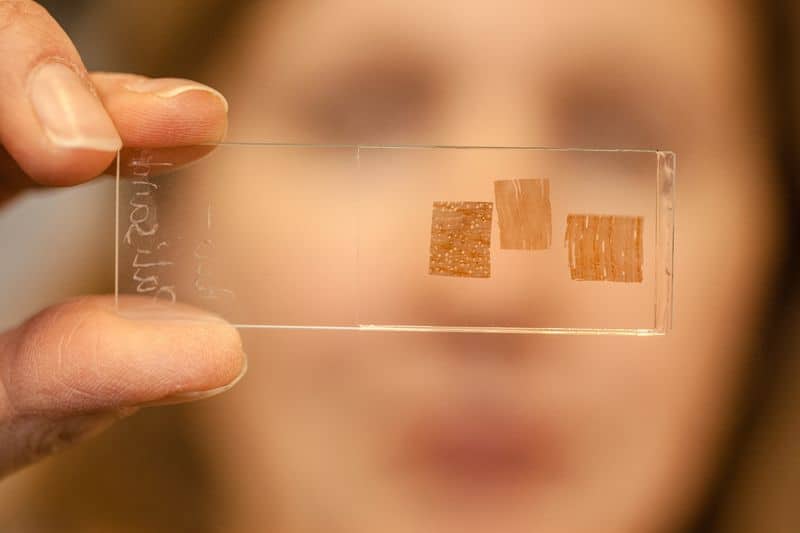

An employee saws a hardwood sample into cubes and boils it until soft, then planes it into 0.02 millimeter slices so he can examine it under a microscope. The scientists identify the wood’s anatomical features, comparing them with the institute’s 50,000 microscopic samples, all of them logged in a digital database. The database calls up the most important of the 100 defined anatomical features, reducing the number of possible species of the sample down to a handful.

“But sometimes the determination takes hours, or in rare cases, even days,” says Koch. In those cases, he and his team turn to larger, international databases or the Center’s in-house wood collection. There are about 35,000 samples of 12,000 species of wood stored here. Many of them still bear the inscription of the predecessor institute founded in 1939.

The Center of Competence has also developed new methods using gene markers to determine where a piece of wood originally grew, accurate to within a few hundred meters. For this, they need reference samples from the region in question. The process of building out complete collections of these samples will take years, but they’ve already covered the entire region of origin of white oak from North America, Europe and Asia, as well as European and Siberian larch, all of which are among the most traded woods of recent years.

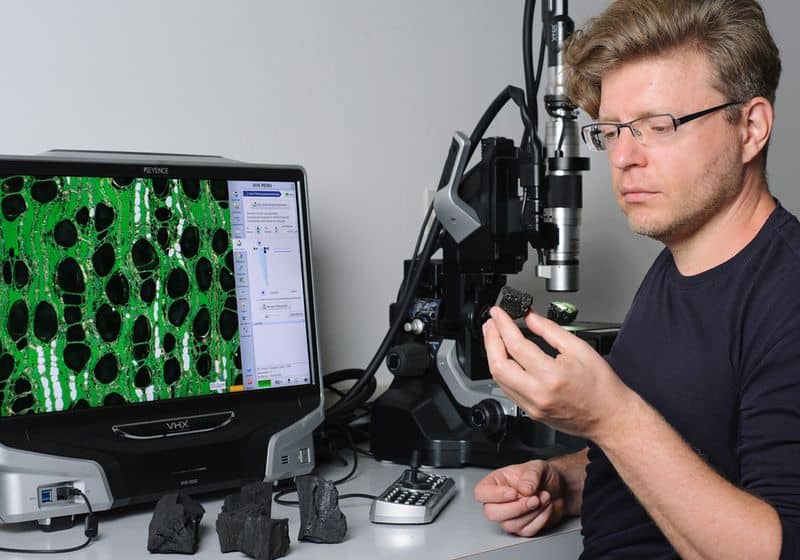

Meanwhile, they’ve scored more than a few coups. In 2018, as partners on a WWF investigation into 60 charcoal brands, Koch and his team detected illegal tropical wood in barbecue charcoal briquettes. The WWF ultimately discovered that one-third of the contents of the briquettes were improperly declared. The result shook the industry, and one of the largest charcoal producers was stripped of its sustainable forestry accreditation.

The charcoal scandal was revelatory not only for its reach, but the way it was unearthed. Brittle charcoal briquets can’t be sliced, so the scientists broke them into pieces. They placed the broken edges under a 3D microscope that was developed only a few years ago, scanning the different heights of the fractured planes and assembling them into an image. Within a few seconds, a high-quality reproduction was on the screen, showing pores, storage cells and other distinguishing features, which were used to determine the species of wood, even though it was burnt to a crisp.

The wood detectives also developed new methods for examining paper, which allowed them to work with Greenpeace to detect ramin wood in the paper of a Chinese manufacturer in Indonesia. Ramin, a threatened species that’s been targeted by illegal traders for years, is protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The swamp forests of ramin in Borneo and Sumatra provide a critical habitat for Indonesia’s orangutans, which is why that country has banned its exportation since 2001.

The wood detectives’ record is impressive. Since the Center of Competence was founded seven years ago, the number of inspection orders has increased annually by 30 percent. Last year, Koch and his team prepared almost 1,600 reports based on about 25,000 individual samples. Many inquiries come from other European countries, such as Great Britain, Austria, the Benelux countries and Switzerland.

The clients are customs and environmental authorities, as well as private interests. Four-fifths of the tests are commissioned voluntarily, mainly by timber merchants, home and hardware stores, and environmental and consumer protection organizations.

For Koch, the rising interest in his work bodes well for the world’s forests. “We are noticing an increasing sensitization, especially in the trade,” he says. “This will have an impact on timber producers around the world.”

All photos courtesy of the Center of Competence on the Origin of Timber.