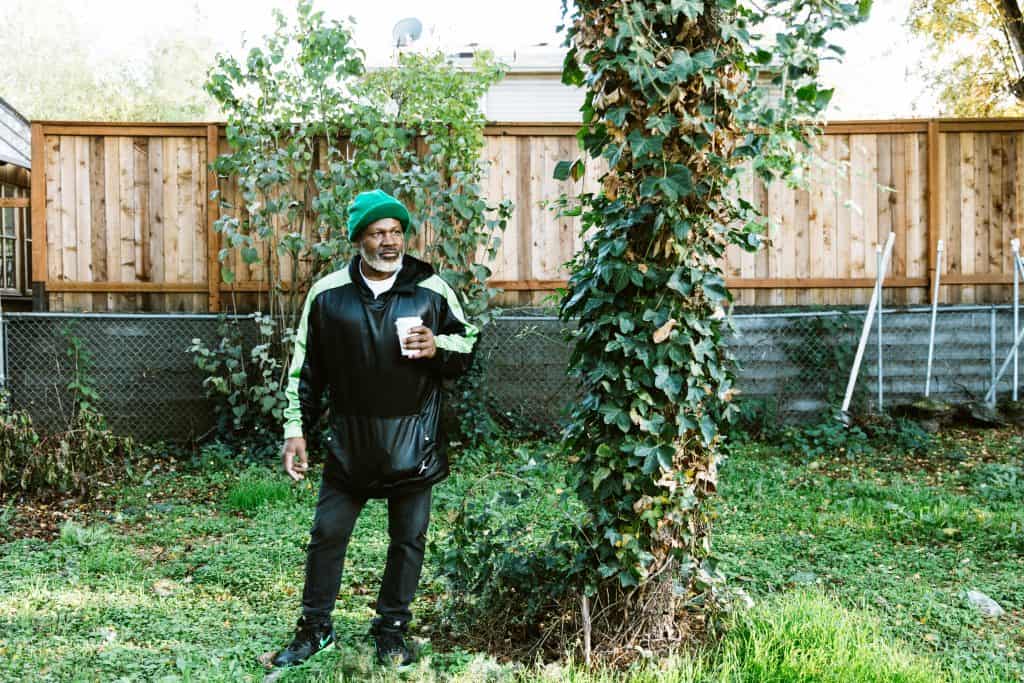

A former professional boxer who has spent 30-plus years training young men how to fight, J.C. Wade wasn’t exactly used to asking for help.

“I’m the proud man guy, you know?” says the resident of Woodlawn in Northeast Portland. “Don’t want to let nobody know I need help.” But now he freely admits that he needed it.

Wade, 68, has four types of arthritis and recently went through prostate cancer treatment. The chemotherapy exhausted him and he had to quit his job as a city bus driver. Stuff piled up around his house. But his biggest issue was the kitchen sink. The pipe had clogged, and because the sink was built into the cabinets they’d have to replace the whole thing, which he couldn’t afford. “So for about four years, I had a big pot up under the sink that the water would run in,” he chuckles, “and I would filter the garbage out and pour the water down the toilet.”

Then, in August 2020, Wade got a call from a friend who told him about Taking Ownership PDX, an organization that helps Black homeowners age in place. Taking Ownership PDX is oriented toward longtime residents like Wade, who bought his ranch-style house in Woodlawn in the mid 1980s. Six of his ten kids grew up there.

The group focuses on maintenance to keep houses livable, making long-needed repairs and renovations to decaying decks, sagging roofs and failing plumbing. In so doing, the organization aims to generate wealth for Black homeowners, deter predatory investors and realtors, and prevent communities from being splintered by gentrification.

Woodlawn is just one of Northeast Portland’s historically Black neighborhoods that, over the past decade, has seen an influx of younger, wealthier and mostly white homeowners. Residents who grew up in Woodlawn now can’t afford to live there; median home prices are $551,000, according to Zillow. Longtime homeowners like Wade are more than just property owners, then. They’re an essential part of the city’s fabric whose presence gives the neighborhood a sense of continuity.

When he applied for help with Taking Ownership PDX, Wade had no idea what to expect. “I wasn’t used to people helping me,” he says. Then a team of eight showed up at his house. They dismantled a rotting shed, fixed up the yard, cleaned the basement and repaired that sink — without even needing to replace the whole thing.

“They helped for days!” Wade says, astonished. “My yard was overgrown — I had dumpsters worth of overgrowth. But they cut it, cleaned it. I haven’t really seen my yard in years. It looked like a jungle. And they kept coming back, you know? It relieved a lot of pressure off of me. I get a little teary-eyed thinking about it. Let me get my man-up stuff!”

Wade’s house was one of Taking Ownership’s first projects. Since then, the group, founded by 36-year-old Randal Wyatt in July 2020, has helped over 50 Black homeowners across Portland. The organization has raised over half a million dollars and maintains a database of 250 local volunteers who are eager to pitch in on the projects whenever they arise.

Wyatt, a native Portlander, has always been a helper. Before Taking Ownership, he was a student advocate at Portland YouthBuilders, worked with teenagers at the Latino Network, and served as a residential treatment counselor at the Salvation Army. When he had twin boys at 19, he learned the importance of strong communities.

“Becoming a father so young, I realized real quickly that life is much bigger than me,” Wyatt says. “We live in a capitalist society where we think very individualistically. I thought, ‘I have to contribute to the community.’ I care about other people.” For the past 16 years, he has used hip-hop to address social issues, reaching teens with rhythm and poetry workshops, and holds benefit concerts for various causes. After the murder of George Floyd, friends and neighbors reached out to see how they could be stronger allies to Portland’s Black community.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Since he was 11, Wyatt has lived in Northeast Portland and watched it gentrify. “I know that white supremacy is based on land ownership. So I just thought, if we pool our money together and come together as a community and fix up Black-owned homes, we might be able to alleviate the financial burden, bridge the wealth gap, raise property values and help people stay in their homes.”

When he launched Taking Ownership he posted about it on Instagram. Donations started pouring in. After the first two projects, word spread quickly. “It blew up almost overnight,” he says. After that, Black homeowners interested in getting help filled out referral forms on the Taking Ownership website. Then they’d go onto the waitlist. Wyatt says senior citizens, people on a fixed income and single parents get priority.

“We prioritize people who make $20,000 or less a year. We’re very clear about that,” he says. There are currently 120 people on the waitlist.

Wyatt has partnered with other organizations and companies that donate appliances and services so that people waiting can get things they desperately need like new water heaters or air conditioners. After June’s record-breaking heat waves, Taking Ownership sponsored an AC and fan drive and collected nearly 200 fans and air conditioning units in a single day. For some Black Portlanders, like J.C. Wade, it was the first time they had ever had AC. “It was just a small air conditioner and it’s in one room, but it was enough for me and my dogs to make it,” he says.

In addition to the hundreds of volunteers who do yard work, sorting, cleaning and other tough, non-skilled labor, Wyatt works with four licensed contractors who handle structural projects like decks, windows and roofs. He also works with two Black-owned landscaping companies, an electrician and a plumbing company, and has, on several occasions, partnered with a Latino-owned roofing company and a green design/build firm called Birdsmouth. All the contractors are paid, unless, like Birdsmouth, they donate some of their labor.

One of his contractors is James Mwas Njoroge of Jenga Construction LLC. Njoroge, who moved to Portland from Kenya in 2005, has been a contractor for 10 years and recently launched his own company. He’d been following Wyatt on social media when he read about Taking Ownership. “What he is doing is very very important, and not just for the homeowners,” Njoroge says. “He’s trying to get Black people more opportunities to work.” There aren’t many licensed Black contractors in the Portland area, but Njoroge is hoping that will change. Over the next year, he aims to help Wyatt reach out to Black youth and encourage them to enter the trades.

Jed Overly was Taking Ownership’s first volunteer before becoming the organization’s volunteer coordinator. A Black man who grew up in rural Pennsylvania, he’d experienced racism up close. “Everything that was going on at that time [after George Floyd’s murder] triggered my internal convictions,” he says. “Taking Ownership gave me an outlet to make things better. I attended a lot of protests. But I’d ask myself, ‘But what are we doing, though?’” Instead of tearing something down, he wanted to build something up. “And that’s literally what Randal was doing.”

Overly says that even now, 16 months after Taking Ownership launched, he still gets 10 to 15 new volunteers a week. About 25 percent are Black, compared to just six percent of the city at large. Volunteers often work alongside homeowners, or homeowners’ children or grandchildren. One of the things Overly loves about the work events is that people make long-lasting connections. “Volunteers are swapping numbers. People are becoming friends,” he says. Some people even become friends with the homeowners. “So you have little old ladies who need help rearranging their house. They get the volunteer’s number. It really is community-building.”

Samantha Guss, who has worked on four projects, says she’s ripped out a lot of blackberry bushes. “I’m pretty sure every project has a blackberry bush,” she says. She’s also dismantled fences, scrubbed floors and helped sort through personal belongings. But all the hard work is worth it, she says, when you see how happy the homeowner is. This volunteer opportunity also came at a time when she really needed community. “I was deep into depression with the pandemic, very isolated. So it was really great for me to be able to feel useful. To help someone else that needed it. It really helped my mental health.”

One of the negative consequences of gentrification is that when wealthier people move into a neighborhood, they tend to report their less-well-off neighbors for minor code violations like peeling paint or overgrown grass. A recent analysis by the city’s Ombudsman’s Office showed that Portland neighborhoods with the fastest rising home prices and those with the most racially diverse residents tend to have the most property violation reports. This often results in residents facing escalating fines — and eventually liens — putting families at risk of foreclosure. In Portland, this complaint-driven system disproportionately impacts homeowners of color.

Wyatt hopes to inspire Portlanders to be more compassionate, more community-minded. “As neighborhoods get more affluent, the standard of upkeep changes and maybe some of the homeowners who have owned their homes for 30 years don’t have the same financial abilities as some of their neighbors to maintain their homes,” he says. “I want people to understand: instead of calling the city, why not go over there and meet your neighbor? Why aren’t they able to keep up on their house? Why not lend a hand?”