A Patient Is a Person is a series about how whole-person health is transforming the patient journey. It is supported by funding from UPIC Health.

On a Thursday evening in late October, a small intersection in Barcelona is teeming with life. Half a dozen young parents are chatting in one corner, babies snug in carriers or crawling on a wooden platform on the floor. On a bench, teenagers are comparing their skates over beer, the music from their speakers drowned out by squealing children in Halloween costumes eating birthday cake at a nearby table. Two older gentlemen are sitting in companionable silence; a young girl is learning how to ride a bike without training wheels, pink streamers on her handlebars.

This is Superilla de Sant Antoni, one of five “superblocks” in Barcelona: areas where traffic has been rerouted to prioritize people, community and active mobility.

Building a healthy city requires addressing five key factors: air pollution, noise, temperature, natural spaces and physical activity (or the lack thereof). Since all these factors are influenced by road traffic, superblocks, if done well, have the potential to improve them all.

“Most cities are car-dominated,” says Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, director of the Urban Planning, Environment and Health Initiative at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health. “A lot of public space is given to the car, which could be used in a better way, for example for green spaces, which we know are healthy.” In Barcelona, 60 percent of the city’s public space is devoted to cars, even though people only use them for one in four trips.

Air pollution from road transport has decreased dramatically in the past three decades, but dense urban traffic remains one of the primary reasons cities in Europe are unable to meet safe air quality standards. Air pollution causes cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and is the main environmental health risk in Europe, while the noise pollution from traffic can lead to hearing loss, tinnitus, sleep loss and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Together, the two cause 212,000 premature deaths per year in Europe. Car-centric city design also means higher temperatures, fewer green spaces and fewer opportunities for exercise, which all negatively impact health.

While the statistics on premature and preventable deaths are sobering, they are just one metric of a larger decline in quality of life, warns Nieuwenhuijsen: “Death is the top of the pyramid, but under that you see a lot of disease and GP visits.”

So it is unsurprising that many of the urban innovations developed and tested in cities worldwide — the 15-minute city, low-traffic neighborhoods, low emission zones, lower speed limits — are variations on one theme: reducing traffic and redesigning cities for people instead of cars.

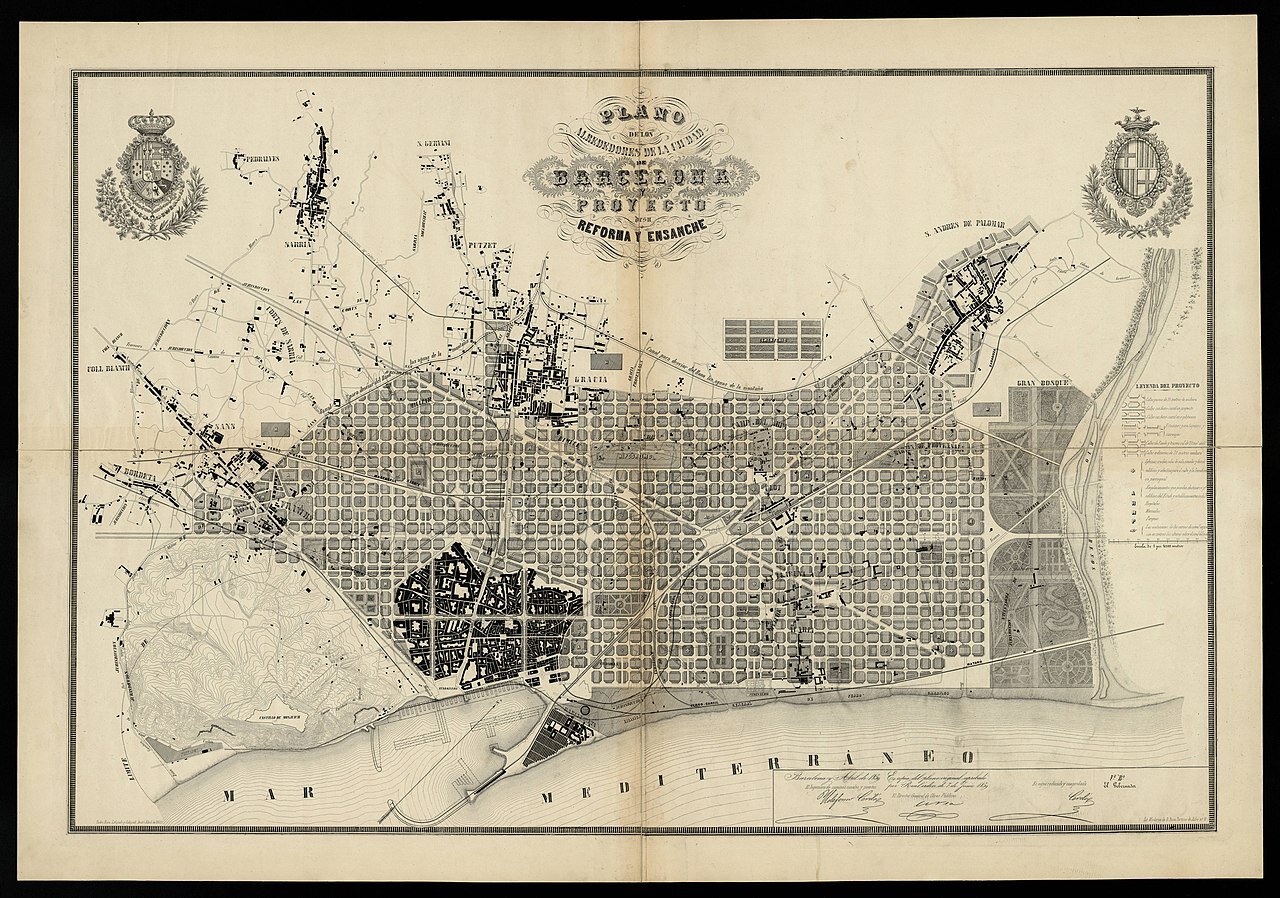

While superblocks are now considered a cutting-edge example of this, their history goes all the way back to 1855, when Barcelona adopted a city expansion plan by the iconic architect Ildefons Cerdà. He envisioned Barcelona as an egalitarian and healthy city in which every resident, regardless of socioeconomic status, had enough water, clean air and sunlight. To achieve this, he designed the city as a grid of blocks, each centered around an open green space and oriented northwest to southeast to optimize sun exposure.

In the end, few of the blocks were actually built according to Cerdà’s vision. By the 1920s the open spaces were already filled with garages, and in the 1960s the wide streets, designed to allow air flow and accommodate tramway lines, were taken over by car traffic. By the early 2000s Barcelona was one of the most built-up cities in Europe, and today leads European rankings both for population and traffic density.

In the 1980s, Salvador Rueda, then head of the Urban Ecology Agency of Barcelona, recognized that the city was on an unsustainable path, so he decided to revive and modernize Cerda’s plan for the 21st century. He developed the idea of superblocks: areas, usually a couple blocks large, that are closed to through traffic and devoted to active mobility and green public spaces. In Barcelona, which is laid out in a uniform grid, the classic superblock is a square of nine blocks intersected by four streets, with two out of three parallel streets closed to vehicle traffic.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The first superblock was created in the El Born neighborhood in 1993, but it wasn’t until 2016 that the city’s new leftist government fully embraced Rueda’s plans, with the goal of creating 503 superblocks by 2030. The start was not promising: The first superblock of the new era, created in 2016 in Poblenou, initially drew protests from residents who didn’t appreciate having to drive their cars the long way around.

Ana Pérez Mendoza, who lived in the Sant Antoni neighborhood when it was turned into a superblock in 2018, recalls similar concerns among her neighbors: “There were two really extreme points of view. I and most of my friends were super happy, because we knew it would decrease traffic. The amount of pollution in Barcelona is deadly — you can’t breathe. But other people were like, ‘First the bike lanes, now the superblocks, it will be impossible to get around the city center!’”

This is by design, says Nieuwenhuijsen: “Most of the time when it becomes a bit more difficult to drive around, people drive less.”

Still, it’s a hard pill to swallow. One of the keys to successfully implementing measures to reduce dependence on cars is explaining the health benefits in concrete terms. “For example, air pollution causes a lot of dementia cases, but people don’t link air pollution with dementia,” says Nieuwenhuijsen. “You need to go out to the different communities and talk to them, and we don’t have the resources to do that.”

In 2021 a study of three new superblocks by the Barcelona Public Health Agency found the areas had decreased noise and air pollution, with the residents reporting a higher quality of life and more social interaction with their neighbors. However, these improvements were marginal, as were the benefits found in other studies.

For more substantial health benefits, superblocks need to be implemented on a grand scale. Creating all 503 superblocks in Barcelona could prevent over 650 premature deaths per year and increase life expectancy by almost 200 days through reductions in pollution, noise and heat, and an increase in green spaces and physical activity, according to a study from 2020.

But it was not to be. In March 2023 Barcelona hosted the first International Superblock Meeting, attended by representatives of 15 other European cities, but by May of the same year the city government changed, announcing that it wouldn’t be continuing with Superblocks due to “costs and dynamics of coexistence.”

“I think that’s really sad, because the idea is good, but like everything in Barcelona it just takes years to figure it out. My superblock was one of the first, they were still testing things out,” says Pérez Mendoza.

By then, the idea had spread to other cities like Vienna, Berlin and Buenos Aires, with Los Angeles planning to follow suit and a geospatial modeling study identifying potential superblock sites in 18 other cities worldwide.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all model,” says Anna-Katharina Brenner, a researcher at the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development who studied the health impacts of potential superblocks in Vienna. Minimal requirements, like traffic diversion and access to public transportation, should be combined with hyper-local implementation, she says: “It’s not enough to just clear a parking lot — it has to be replaced with greenery, or seating, so the benefit is immediately obvious for people. And this should be adapted to what people actually need, which can be very different in different areas.”

Vienna started testing out its first superblock — called Supergrätzl in the Viennese dialect — in 2022, by blocking through-traffic and using temporary interventions like pavement paintings, street furniture and movable greenery. This year, the city started making permanent changes, which includes planting 62 additional trees and adding water features and play areas for children.

The pilot is located in the district of Favoriten, a lower-income area where the environmental and health benefits of a superblock are up to three times higher than in more affluent parts of the city, according to Brenner’s study, which focused on the increase in physical activity. While the study’s results are specific to the mobility patterns of the studied districts, they reflect a larger trend: Residents in lower-income neighborhoods are particularly impacted by traffic and a lack of green spaces, so urban planning interventions like superblocks can be a step towards reducing urban health inequities.

For Pérez Mendoza in Barcelona, the biggest benefit was simply having a pleasant place to hang out with her friends: “There were a lot more people outside, especially kids. It’s nice when they can run around without having to worry about the cars, so there were a lot of families out, people started playing chess tournaments, it was a big shift in the neighborhood.” She hopes that Barcelona eventually decides to continue with the project: “Imagine having superblocks everywhere, it could be so nice for such a crowded and polluted and loud city!”